This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor : India and the World

Background

Now that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has issued higher standards for ambient air quality and most of India has fallen outside the limits for safety, the economic elite will indulge in the politics of outrage to grab disproportionate share of policy attention—time and money. The outrage over how policymakers, especially those in charge in urban areas such as Delhi, have failed to address the health of the elite will reverberate in all media. This outrage will be presented as a collective concern over health of all, but in reality, it is synthetic outrage arising out of the narcissism of the educated and wealthy elite.

Unlike the response to climate change for which there is no historic precedent, the response to local pollution has historic precedents. Cities such as New York and London were highly polluted when they were industrialising and relatively poor. They cleaned up as they got richer. This led to the adaptation of the Kuznets curve to the problem of local pollution. Simon Kuznets, an economist, observed in 1955 that income inequality would grow in the initial stages of development and fall after a peak. Kuznets’s arguments, originally advanced under more limited conditions was transformed into overarching theoretical, empirical, and political constructions by development economists in the 1990s. The inverted U-shaped curve between income and inequality became known as the Kuznets curve and is now widely used in development studies. The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) investigated first in a paper on North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by Gene M. Grossman and Alan B. Krueger, in 1991 was later popularised through the World Bank’s World Development Report of 1992.

Cities such as New York and London were highly polluted when they were industrialising and relatively poor. They cleaned up as they got richer.

According to the EKC hypothesis, in the early years of economic growth, local environmental pollution increases but beyond a level of income per person, which is different for different types of pollution the trend reverses. In other words, local pollution follows an inverted ‘U’ shaped function of income per person. This means that economic growth may be the cause of local pollution in the early years of development but beyond a certain point, it becomes the means to reduce pollution. The income level that initiates concern over pollution is put at about US $4,000 per person which is twice the amount of India’s current per person income that is around US $2,000.

In the early years of rapid economic growth, scale effects of local pollution and environmental degradation dominate over the time effect of pollution reduction efforts. In later years, growth slows down or shifts from heavy manufacturing to services and consequently the time effect of pollution reduction efforts dominates over scale effects of pollution and environmental degradation. Despite its logical clarity, the EKC has not been accepted as the last word on local environmental pollution and a rigorous academic debate continues over its validity.

The EKC influenced the idea of ‘sustainable development’ which essentially said that ‘we can have the cake and eat it too’ when it comes to the environment. Under this perspective, environmental degradation is framed primarily as a problem of poor environmental management. The environment can be ‘managed’ using technology along with economic or legal techniques such as making the polluter pay or mandating limits to pollution (what the WHO has just done). The 1992 World Development report of the World Bank endorsed this view. According to the report:

‘The view that greater economic activity inevitably hurts the environment is based on static assumptions about technology, tastes and environmental investments…As incomes rise, the demand for improvements in environmental quality will increase as with resources available for investments’

The environment can be ‘managed’ using technology along with economic or legal techniques such as making the polluter pay or mandating limits to pollution (what the WHO has just done). The 1992 World Development report of the World Bank endorsed this view.

This observation explains why the first to complain about an environmental problem are not the poor, who are most affected by it but by the wealthy who have few other survival issues (food, water and shelter) to worry about. For example, the complaint over population pressure is not raised by the poor who live in crowded slums where 10 persons share 100 square feet of space but by those who live in large homes with more than 1,000 square feet of space for each member. Likewise, the pavement dweller or the street vendor in Delhi who almost exclusively breathes air polluted by vehicle exhaust and road and construction dust does not raise the issue of pollution. It is the wealthy who occasionally go out.

The politics of outrage

It was the wealthy expat community which wanted to breathe clean air when they went out of their well-insulated and comfortable homes (or cars) to exercise or play that initially raised the issue in the 1990s in Beijing followed by Delhi in the 2000s. They installed air quality monitors in their premises and sent out press releases on the pollution levels in Delhi and Beijing. They coined words such as ‘Beijing cough’ to name and shame the cities which, in their view, were ignorant of pollution management techniques and technologies. The urban economic elite of the respective countries followed up with well-articulated outrage.

Based on a study by Gilens and Page, noted economist Dani Rodrik showed that when the elite manage to frame issues, such as immigration or pollution, as concerns of the poor, such as presenting the impact of immigrants on entry level jobs and wages or linking pollution to deaths, it had a strong positive influence on government response. He cautioned that this could give a misleading positive impression of the representativeness of the government, especially over policies on strong national defence or a healthy economy where interests of the economic elites and the economic destitutes converged. Rodrik pointed out that when the preferences of the economic elite and the economic destitute diverged, it was the economic elites that counted. Rodrik highlighted the powerful impact of well-organised interest groups, which only economic elites and business groups can afford on government policy.

When the elite manage to frame issues, such as immigration or pollution, as concerns of the poor, such as presenting the impact of immigrants on entry level jobs and wages or linking pollution to deaths, it had a strong positive influence on government response.

Gordon Tullock, who pioneered work on lobbying for rent-seeking observed that the influence of lobbyists came from their ‘ability to become an essential part of the policymaking process by flooding understaffed, under-experienced and overworked government offices with enough information and expertise to help shape their thinking’. Think tanks funded by wealthy countries conduct studies on domestic and global pollution that influence environmental policymaking in developing countries. Tullock’s partner in research, James Buchanan, a Nobel Laureate, coined the term ‘politics without romance’ to capture the sentiment of politicians and bureaucrats who as rational actors strive to do what is in their best interest just as market actors do. What is in their best interest is to follow the elite.

Urban Pollution and Electricity Demand

A recent study has found that a significant and hitherto ignored determinant of home energy demand is ambient particle pollution. Throughout the developing world, particle concentrations in outdoor air fluctuate in the visible range—PM2.5 (particulate matter) between 20 and 200 µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic metre). Particles cause smog or haze, which is visible. The naked eye can detect differences in PM2.5 concentrations below 10 µg/m3 vs. above 50 or 100 µg/m3. The hypothesis is that higher PM2.5 induces households to stay indoors more and, instead of naturally ventilating their home, they close their windows and use defensive capital, ranging from portable air purifiers to more powerful wall mounted ACs or heaters. This defensive behaviour, which is a response to ambient pollution, increases energy demand and the greenhouse gas emissions that are typically coproduced to meet that demand. The defensive behaviour has environmental justice implications. Poorer households are less willing or less able to invest in defensive capital, from windows that close to air conditioners and purifiers that to some degree abate indoor particle levels.

Academic Support

Studies that suggest a strong causal link between pollution levels and health generally use statistical and graphical techniques dependent on questionnaire-based surveys conducted amongst a small group of people. These studies essentially establish a link between the health of urban dwellers and urban pollution levels by pointing out that the number of visits to the doctor or events of death were above normal during the periods of pollution. Critiques of such studies point out that the procedures used in these studies are inadequate to establish a clear link between pollution and health problems and that extreme care is required when interpreting such small sets of data. Studies also questioned the use of questionnaires and other voluntary responses to measure the effect of air pollution. They argued that as awareness of high pollution levels is increased by news media, survey responses were likely to be influenced by the nature of news coverage. For example, after the release of the revised air quality norms by WHO and wide coverage of the issue in the media, complaints about health effects of pollution are likely to increase. Some studies also pointed out that people who ‘died’ of pollution would have to have a serious prior illness and that pollution would have merely hastened death by a few days.

Studies that suggest a strong causal link between pollution levels and health generally use statistical and graphical techniques dependent on questionnaire-based surveys conducted amongst a small group of people.

The point being made here is not that urban pollution is not a problem. It is a serious problem, but it gets the attention that it gets because it affects the wealthy. Poverty that stunts growth, results in malnutrition, and ultimately causes disease and death does not get the attention it deserves because it is not a concern of the wealthy. Political leadership that tries to address concerns of the poor are very likely to be voted out because the wealthy are averse to redistributive policies. Elite outrage over urban pollution is more about ‘us’, the rich who are less affected by pollution than about ‘them’ the poor. It will shift scarce public finances raised by taxing consumption of fuels and other goods, a burden that falls most heavily on the poor as it accounts for a large share of their income towards subsidising urban pollution reducing measures such as the purchase and use of electric cars. This is essentially a subsidy from the poor to the rich.

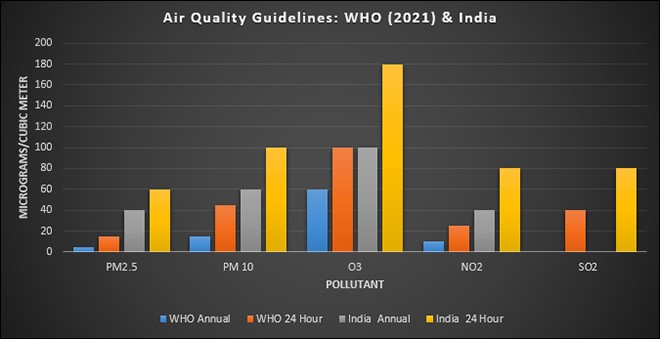

Source: WHO for WHO revised air quality guidelines and Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) for India

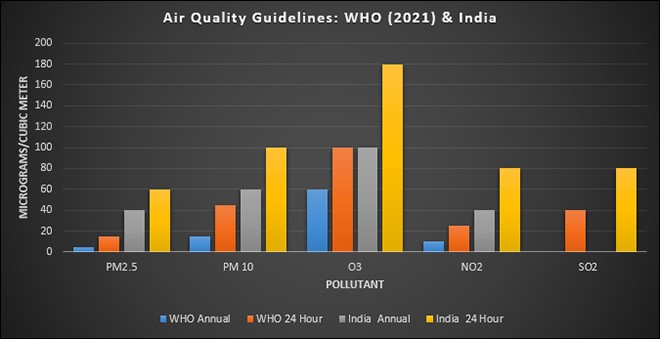

Source: WHO for WHO revised air quality guidelines and Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) for India

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV