In the early 2000s, the dominant view in the Indian energy policy community was that natural gas would emerge from the role of an unwanted step sister of oil to Princess Cinderella, who would put India on the bridge to a low carbon future. The optimism was based partly on the exuberant projections for domestic gas production and partly on the expectation that natural gas with the lowest emission of CO2 (carbon dioxide) among fossil fuels will succeed in displacing coal in power generation and oil in transportation. Two decades later, these expectations have not materialised to the extent expected.

The optimism over prospects for gas discoveries in India was triggered by large finds in the deep waters of the east coast of India in 2002 which were the world’s largest for that year and India’s largest since 1970. Based on projections of reserves that could be tapped, some technical experts even believed that India could potentially become a natural gas surplus country. The DGH (Directorate of Hydrocarbons) of the Government of India projected GIIP (Gas Initially in Place) accretion of 7.35 tcf (trillion cubic feet) in 2002-2003 and 9.37 tcf in 2006-07. Assuming a reserve accretion rate of 1 percent per year, production in 2019-20 was estimated to be about 145 mmscmd (metric million standard cubic meters per day) which if realised would have met most of India’s natural gas demand today (2019-20). Under a 5 percent per year reserve accretion rate, production was estimated to exceed 1,000 mmscmd that would have generated exportable surplus of natural gas at current levels of gas consumption.

The optimism over prospects for gas discoveries in India was triggered by large finds in the deep waters of the east coast of India in 2002 which were the world’s largest for that year and India’s largest since 1970.

The exuberance over natural gas discoveries in India was not completely irrational. Less than 20 percent of the 3.14 million km2 (square kilometres) of the sedimentary basins in India were fully explored and there was optimism that discovery rates would improve with investment in exploratory drilling. The NELP (New Exploration and Licensing Policy) had opened up the sector in India and 49 companies were operating in 10 producing basins. This was a substantial increase compared to 2 public sector companies operating in 3 producing basins in the 1990s. Deepwater drilling technology was booming around the world in the 2000s especially in the US Gulf of Mexico endorsing prospects for deep-water discoveries of hydrocarbons. Globally the dominant narrative was that of an impending scarcity of natural gas which pushed up the price of imported and domestic natural gas. Imported LNG (liquid natural gas) was trading at an average of $12.55/mmBtu (metric million British thermal units) in Japan in 2008 and US domestic gas was trading at an average of $8.85/mmBtu. Countries endowed with large reserves of natural gas such as Russia were preparing to become energy superpowers. The 2010 issue of the world energy outlook brought out by the IEA (International Energy Agency) optimistically asked if the world was entering a “golden age of gas?” Reality did not play out as expected, especially in India.

In 2010 the share of natural gas in India’s primary commercial energy basket (not including non-commercial energy sources) was 9.4 percent which fell to 6.2 percent by 2018. In 2012 natural gas accounted for roughly 10 percent of gross electricity generation but in 2018 natural gas accounted for less than 4 percent of gross generation (CEA 2018). In 2018-19, India produced just over 87 mmscmd of natural gas while it consumed 166 mmscmd of gas which means that about 78 mmscmd (just over 47 percent of consumption) of gas consumption was imported.

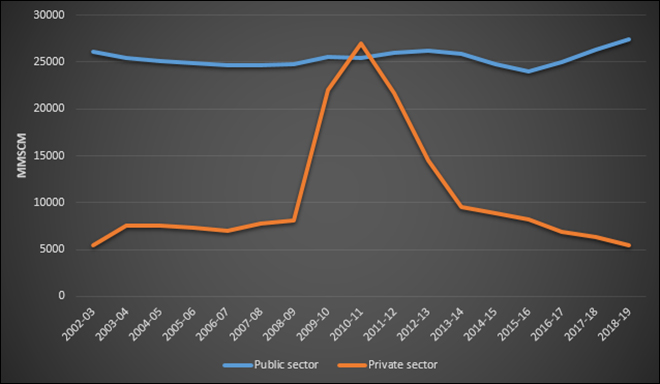

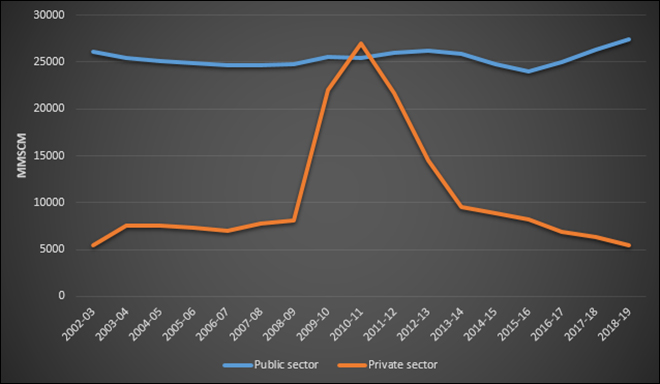

Domestic Production of Natural Gas 2003-2019

Source: PPAC, MOPNG, Planning Commission

Source: PPAC, MOPNG, Planning Commission

Natural gas production by the private sector briefly exceeded production by the public sector in 2010-11, but it fell dramatically after that (chart). Overall domestic production of natural gas fell by an annual average of over 5 percent between 2010-11 and 2018-19. This obviously meant a dramatic reduction in the availability of cheap domestic gas for the power and fertiliser segments traditionally seen as the anchor customers for gas. Consumption of gas by the power sector fell by over 8 percent from 62 mmscm in 2011-12 to about 33 mmscm in 2018-19. Even industrial consumption fell by over 7 percent from 34 mmscm to 20 mmscm in the same period. Overall natural gas consumption growth fell by over 5 percent from 2010-11 to 2014-15.

Double digit growth rates in natural gas consumption can be sustained only by an economy expanding at close to double digit growth rates.

Since 2014 demand for natural has picked up primarily because of targeted policies to increase the use of PNG (piped natural gas) as fuel for cooking and CNG (compressed natural gas) as fuel for urban transport through city gas distribution (CGD) networks. In the period 2014-15 and 2018-19 consumption of natural gas through CGD networks increased by 13.6 percent. Gas use by the refineries in India also increased in the same period by over 9 percent driven primarily by the ban on pet-coke use. Most of this growth was met with imported LNG which has grown by over 11 percent since 2014.

For natural gas to increase its share to 15 percent in India’s energy basket the average growth rate of natural gas consumption has to double from 6.3 percent in 2008-09 to 2018-19 to 12.4 percent in 2018-19 to 2029-30. Double digit growth rates in natural gas consumption can be sustained only by an economy expanding at close to double digit growth rates. But double digit economic growth rates alone may not accelerate demand for gas if well targeted policies and incentives are not put in place.

In the next 10 years, the CGD sector can add about 250 mmscmd to consumption and make the biggest contribution (about 60 percent) to increasing the share of gas. There is optimism in the industry after bidding rounds have been completed for 228 geographic areas (GAs) comprising of 402 districts covering 27 states in which 70 percent of the population of the country live. Currently Delhi, Mumbai and the state of Gujarat (which has a large number of industrial consumers) account for over 80 percent of CGD gas consumption. Growth in CGD outside these consumption centres is likely to be slow. The population density (population per square km) of Mumbai is about 20,500 and that of Delhi is about 11,250. Most of the licenses issued for new CGD connections are for cities and regions that have population densities that are lower by an order of magnitude. Low population density is significant economic barrier in increasing the number of PNG consumers from the current 5 million but continued policy push with the right incentives can overcome the barrier.

If policy aims to increase the PLF (plant load factor) of existing gas based power generation capacity to 85 percent, the normative gas requirement of about 102 mmscmd must be made available to the plants.

In the power sector, the PLF (plant load factor) of existing gas based power generation capacity of 25 GW has fallen to 24 percent on account of shortage of domestic gas since 2011-12 (Ministry of Power 2019). In 2017-18 domestic gas allocated to the power sector was 87.12 mmcsmd but average domestic gas supplied was 25.71 mmscmd. If policy aims to increase the PLF of existing gas based power generation capacity to 85 percent, the normative gas requirement of about 102 mmscmd must be made available to the plants. Since most of this gas is likely to be imported, policies to ensure offtake of gas based power which is not likely to be competitive compared to coal based power in the long-term must be put in place. This may have to take the form of obligations on distribution companies (discoms) to purchase gas based power (“gas purchase obligations”) similar to renewable purchase obligations (RPOs). Given the poor financial health of discoms, imposing additional obligations on them will be difficult but as in the case of renewables (and now hydro) it is not impossible.

To increase gas consumption in the industry and other segments that could potentially add about 68 mmscmd to consumption, pipeline connectivity must increase substantially in the next decade and incentives to consume gas against cheaper alternatives such as coal must be put in place. LNG transported by trucks could potentially substitute for pipelines but that would make gas less competitive. Overall prospects for increasing the share of gas in India’s energy basket are limited by lack of infrastructure (access) and also by affordability especially in sectors where substitutes such as coal are more competitive. In sectors where gas competes with oil, tax arbitrage favours gas but gas can leverage this advantage only in regions where gas is accessible. Access can be improved with investment in infrastructure.

With domestic coal prices below $50/tonne, imported or domestic gas prices have to be way below $4/mmBtu to compete with coal. Current Asian LNG spot prices are below $3/mmBtu with month ahead prices for March below $2.92/mmBtu on account of low demand made worse by the impact of corona virus. (OIES 2019). These prices are below the long-run marginal cost of delivering gas for domestic gas suppliers and also for international suppliers. Market linkages between gas and oil are gradually loosening at least when it comes to pricing arrangements. However, there are upstream ties between oil and gas that are more difficult to undo. This is evident in India where domestic producers of natural gas continue to emphasise the need to raise gas prices to support further upstream development of more complex non-associated gas projects. Supplying high cost domestic gas to sectors reliant on low cost gas supply will be difficult without additional policy support in the form of carbon price or mandatory purchase obligations.

Market linkages between gas and oil are gradually loosening at least when it comes to pricing arrangements. However, there are upstream ties between oil and gas that are more difficult to undo.

In the context of emissions, it is well established that gas scores over coal and oil. Coal to gas switching is generally seen as the means to rapid reduction in CO2 emissions. Typically, natural gas emits 50-60 percent less CO2 when combusted in an efficient power plant compared to emissions from a typical coal plant. Considering only tail-pipe emissions, natural gas used as fuel for transportation emits 15-20 percent less emissions than petrol when burned in a modern vehicle.

But there is the environmentalist argument that gas is not necessarily carbon free and investment in gas supply chains would lock in emissions and create new path dependencies that would only extend the life of fossil fuels. The conclusion is that facilitating natural gas use is inconsistent with the goal of decarbonisation and it would potentially create stranded assets. The fact that LNG supply chains produce more emissions per unit gas than pipeline gas because of the additional energy required for liquefaction is used to strengthen the case against gas.

The global carbon project (GCP) has pointed out that in 2019, though gas contributed to a 1.7 percent fall in global emissions on account of coal to gas switching, emissions from gas exceeded emissions from coal in the US and in Europe. In the US, coal to gas switching was driven by the price competitiveness of gas over coal and in Europe coal to gas switching was driven by high carbon prices. US CO2 emissions from gas reached 1.7 GT (giga tonnes) in 2019 which was a 3.5 percent increase over emissions in 2018 while emissions from coal decreased by 10.5 percent to 1.1 GT. In Europe emissions from gas increased by 3 percent to 1 GT while emissions from coal decreased by 10 percent to 0.8 GT. Even in China emissions from gas increased by 6 percent to 0.6 GT in 2019 but Chinese emissions from coal are orders of magnitude higher than that from gas. While increase in CO2 emissions from gas use is real it is not rational to eliminate the option of gas as a fuel that can replace oil and coal while also lowering relative emissions.

Renewable energy has not been able to meet this demand because of its inherent challenges that increase transaction costs (system level) in harnessing electricity generated with renewable sources.

The reason why emissions from natural gas is going up in the US, Europe and China is because gas is meeting growing demand for energy in these regions. If this demand was met by coal or oil, emissions would have been higher. Renewable energy has not been able to meet this demand because of its inherent challenges that increase transaction costs (system level) in harnessing electricity generated with renewable sources.

If India decides to meet growing demand for energy with solar or wind energy massive investment in storage and transmission capacity must be made. If the US electricity system relies entirely on renewable energy, electricity supply with 99.97 percent reliability will require 12 hours of storage (estimated to cost about $2.5 trillion) and at least twice the amount of renewable energy generating capacity. India’s electricity system that is roughly a quarter of the size of US system would have to invest quarter of its GDP in storage alone. Costs may decline and technologies may improve for renewable energy but until then natural gas is a realistic option.

Natural gas can provide ‘always-on’ power and in addition provide quick ramp up and down to meet fluctuating demand at a fraction of the cost. During the recent pan India ‘switch-off’ of lighting load on 5 April 2020, it was the quick ramping capability of natural gas power (along with a much larger share of hydro power) that maintained grid stability when 31 GW of load was lost and regained within 10 minutes. Natural gas (along with coal) has the capacity to become carbon free if new technologies for carbon capture prove to be commercially successful. The Allam cycle in power generation that can in theory capture all the CO2 that is produced without significantly increasing the cost is one such promising technology. Investment in gas pipelines is unlikely to become stranded assets as they can transport of hydrogen, a zero carbon energy carrier that can become the fuel of the future. Yes natural gas is not too hot in affordability nor cold enough in emissions but like Goldilocks’ porridge, it is just right for India which has to meet the competing needs of rapidly increasing the supply of energy and simultaneously reduce emissions.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: PPAC, MOPNG, Planning Commission

Source: PPAC, MOPNG, Planning Commission PREV

PREV