The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the cracks in the global labour markets. The

United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 calls for full and productive employment for all men and women around the globe by 2030. To achieve this goal, a high level of sustained economic growth is needed, especially in developing and emerging economies where a significant proportion of the workforce is in some form of vulnerable employment or is living in extreme poverty. The unemployment issue is further compounded due to the shrinking economy caused by the pandemic, leaving the progress towards SDG 8 on uncertain grounds. In the Indian context, where

9.83 percent of the formal workforce is unemployed as of August 2020, the sustained 8.5 percent GDP growth needed to accommodate the 10-12 million youth in to the formal economy every year is not being achieved.

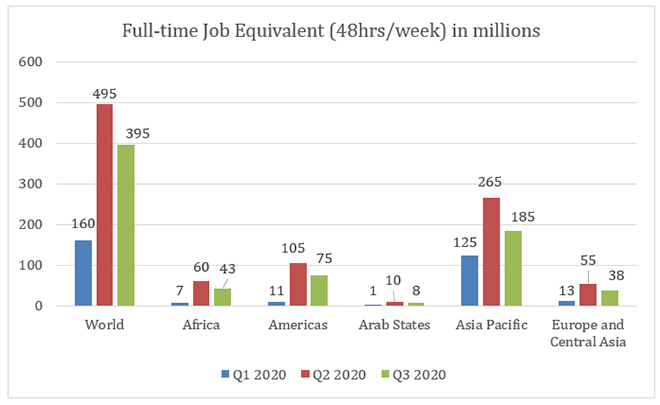

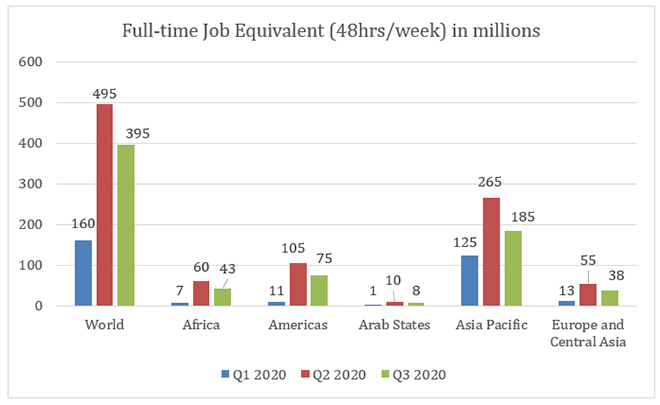

The social and economic restrictions enacted during the pandemic has led to a grave increase in unemployment, which involves employers not hiring new workers while laying off existing ones. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has estimated that globally 495 million people have lost their jobs in the second quarter of 2020, which is more than three times of the first quarter unemployment figure of 160 million. Although the estimates for the third quarter is lower at 345 million jobs, the

predictions for job losses in the last quarter of 2020 ranges from 160 million to 515 million. As the world reels under the economic pressure created by the pandemic, the need for radical policies is of utmost importance to strike a balance between the health and economic impacts of COVID-19.

Figure 1: Job losses by regions in the first three quarters of 2020

Source: Author’s own, data from ILO Monitor on COVID-19, sixth edition.

Source: Author’s own, data from ILO Monitor on COVID-19, sixth edition.

There has been a significant decrease in demand for goods and services, resulting from a bearish economic outlook coupled with disruptions in supply chains. It has been predicted that the impact of COVID-19 on labour market outcomes will be felt in three major ways, i.e. quality of jobs, quantity of jobs, and related effects on vulnerable groups. Mainly due to the lockdown imposed in India during late March, the GDP in the second quarter of FY 2020-21

contracted by 23.9 percent y-o-y - with similar contractions reported in other economies like the United States (31 percent) and Europe (14 percent), during the same period. The most significant impact of the virus has been the resultant labour market shock leading to hiring freezes, loss of a market for informal labour, workplace closures and mass layoffs across firms.

The impact of COVID-19 on labour market outcomes will be felt in three major ways, i.e. quality of jobs, quantity of jobs, and related effects on vulnerable groups.

Fiscal measures and loss in working hours

Although contemporary economic theory focuses on achieving economic stability by targeting aggregate demand and GDP growth, this is in stark contrast to the Keynesian theory where macroeconomic stability is inextricably linked to full employement through public welfare schemes. In fact,

studies show that fiscal policies that are directed towards labour demand gaps instead of mere output gaps are more effective at tackling unemployment, attaining income equity and inducing prudent investment decisions. In India, the government sponsored MGNREGS programme has effectively helped build rural infrastructure and labour markets while setting a benchmark for wages. As proposed by economist Jean Dreze, a demand-driven

urban employment programme could also help in urban infrastructure rejuvenation while providing employment to millions of urban poor, when they need it the most.

Governments need to use expansionary fiscal policies to diminish the huge loss in consumption demand due to the sharp rise in global unemployment. It can be done through a variety of measures including, public works programmes, income support to mitigate demand side shortages, providing subsidies to businesses to encourage investments, and expenditure on social and healthcare services.

There is no doubt that teleworking is not a feasible option for a large proportion of the global working class and business owners. According to the sixth edition of the

ILO Monitor on COVID-19, using the baseline of the last quarter of 2019 — during the second quarter of 2020, 17.3 percent of working hours were lost (mainly due to workplace closures), compared to 5.6 percent in the first quarter, with estimates of lost working hours at 12.1 percent in the third quarter and 8.6 percent in the last quarter of 2020. These reduced working hours have caused labour incomes to decrease by 10.7 percent globally, in the first three quarters of 2020 on a y-o-y basis.

There is no doubt that teleworking is not a feasible option for a large proportion of the global working class and business owners.

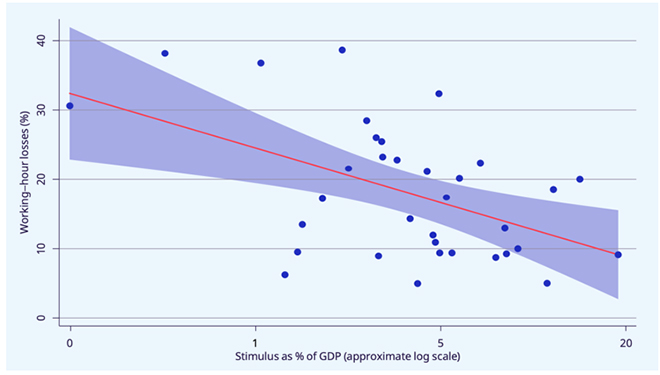

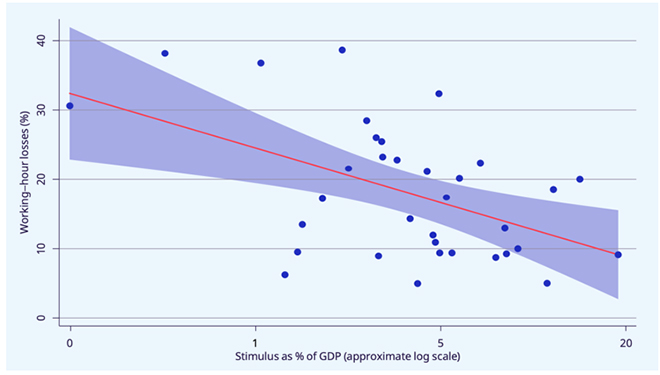

A strong

negative correlation can be found for countries with a larger fiscal stimulus (as a percentage of GDP) and loss in working hours as measured in the second quarter of 2020 (compared to the working hours in the last quarter of 2019). The particular

ILO report also found that the higher losses of jobs in low-and middle-income countries could be the result of lower amounts of fiscal stimulus. There was a wide variation in fiscal stimulus packages across countries in different income groups, in relation to the corresponding job losses in those countries. High income countries announced an average stimulus package of 10.1 percent of their GDP, compared to the working-hours losses of 9.4 percent, whereas in low income countries with the average working-hour losses at 9 percent, the average stimulus package was only 1.2 percent of their GDP.

Figure 2: Relationship between fiscal stimulus and losses in working hours in Q2 of 2020

Source: ILO Monitor on COVID-19, sixth edition.

Source: ILO Monitor on COVID-19, sixth edition.

In India, the recent fiscal budgetary support to address demand shortages was a meagre

1.2 percent of the GDP. Since the fiscal stimulus is a small in comparison to the contraction in growth, it might not be able to single-handedly provide the much-needed income support to get India’s economy back on track. It is estimated that a one percent increase in a nation’s GDP due to fiscal stimulus could have helped reduce working-hour losses by 0.8 percent in the second quarter of 2020 as compared to the working hours in the last quarter of 2019. It is interesting to note that around the end of September 2020 in the United States, the number of

people filing for unemployment benefits started rising again as the government stimulus package, used by businesses to recall furloughed and laid-off workers, was starting to run out.

Looking ahead

Given the immense scale of the crisis, proper establishment of sustainable solutions of a corresponding magnitude, with due considerations given to health implications, is needed on a regional and global scale. Businesses can also innovate with their service delivery while

retaining employees to survive in the market. Some companies when forced to shut down physical stores, redeployed their sales staff to conduct online sales, even managing to expand their operation. Other businesses have managed to redeploy their existing infrastructure and expertise to make COVID-19 relevant products with cosmetic and alcohol companies switching over to sanitiser manufacturing and car companies making ventilators. Companies have also helped laid-off staff transition to newer in-demand jobs — like taxi-aggregators now delivering e-commerce goods or airline staff trained in CPR working for hospitals.

Proper implementation of these measures will help restore trust.

Additionally, the ‘

stimulus gap’ between high-and low-income countries needs to be tackled with debt relief and restructuring to have better outcomes for people through international solidarity. Above all, these measures need to be implemented in a timely manner with a strong emphasis on dialogue with multiple stakeholders like governments, employers and workers. The proper implementation of these measures will help restore trust in institutions and will be extremely critical to contain the economic impact caused by this global pandemic, especially for people in economically vulnerable positions.

Soumya Bhowmick is Junior Fellow and Suyash Das Research Intern at ORF Kolkata.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the cracks in the global labour markets. The

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the cracks in the global labour markets. The  Source: Author’s own, data from

Source: Author’s own, data from  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV