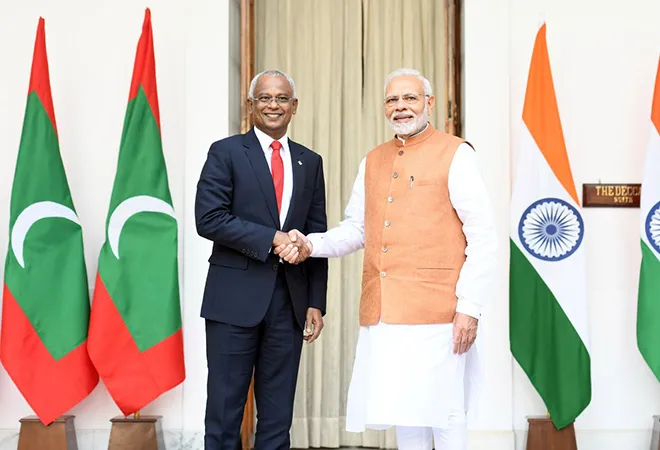

In what could be considered a new beginning in India’s aid policy for the neighbourhood, Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed New Delhi to a high $1.4-b aid to Maldives during new President Mohamed Ibrahim ‘Ibu’ Solih’s maiden overseas official visit to New Delhi (17-19 December 2018). Independent of larger aid to nations like Bangladesh, for long, a section of India’s neighbourhood policy-thinkers have been recommending a ‘free-purse’ policy if New Delhi was serious about offsetting Chinese and other third-nation ‘economic strangulation’ of the neighbourhood.

The Indian aid package comprises $ 200 m credit-line for what has become near-customary budgetary support. Of this, $50 m will be free aid while the remaining $ 150-m will be invested in the Maldivian Government’s ‘Treasury-Bills’ (T-Bills). President Solih said at a news conference on his return to Male that “under our agreement, the interest rate for the T-Bills will be a low 1.5 percent.” He pointed out that “the previous administration (of President Abdulla Yameen) sold T-Bills for very high interest rates, like five percent, six, eight...”

The path-breaking Indian initiative in the ‘neighbourhood aid policy’ came in the form of a $800 m to fund infrastructure development projects in Maldives. President Solih was quick to clarify/reiterate at his Male news conference that “This does not mean, we take $800 m in bulk and fall into debt. Instead, India will loan the required amount of funds for projects proposed by the government.”

Solih very clearly indicated that the Indian aid was for ‘judicious use’. Given his election agenda, it is likely that his government would propose small and purposeful projects aimed at improving the civic infrastructure in individual islands and atolls than going in for mega-projects of the Yameen kind. The former is people-centric, addressing their needs, while the latter was regime-centric, aimed at bolstering the leadership’s public image, but did not serve the purpose as the presidential poll results showed.

Safety clause

In this context, Solih clarified that the two governments have agreed that the contractor for each of these projects would have to include a local partner. Such a course, it is believed, is likely to pave the way for profit-sharing with Maldivians, apart from eye-catching projects like the Male-Huhumale sea-bridge, conceived and built in record time when Yameen was in power.

The Indian approach to aid-policy is unlike most big-ticket Chinese investments for Maldives and other Third World nations, in South Asia and elsewhere. The ‘local partner’ concept will also help ensure an element of transparency for the local government and population, as ‘our man/stake-holder is there, to keep an eye and report back’. This should give the Maldivian polity and people an element of confidence in their systems and foreign investors’ methods.

In the absence of such ‘safety clause’ to protect the host-nation’s interests and address their concerns, China, for instance, has been bringing in the money, incidentally the labour too, and there is minimum information-sharing within the host nation. This has led to situations of constant Opposition barraging of an ‘impending debt-trap’. The charge has proved true in most cases, though figures may be less than believed.

At one stage the Chinese investments was believed to be around $ 3.5 b, all incurred under the erstwhile Yameen regime. However, after the Solih government came to power on 17 November, government auditors have confirmed that the Chinese debt was a high $ 1.5-b, beyond Maldives’ ordinary repayment capacity.

Solih has clarified that the Indian aid would not be used to pay back China, either in part or otherwise. This would mean that India was not starting of an ‘economic war’ with China in the neighbourhood. Instead, New Delhi, at the best, was only thinking in terms of helping neighbourhood nations to minimise their dependence on a single source of credit. Under the Nasheed presidency, for instance, the dependence on the IMF credit, too, became a political issue that weakened his public support after the attendant conditionalities taxed the people in more ways than one.

India will also provide $ 400 m for currency-swap, Solih said. This, he pointed out, would help Maldives sustain the nation’s foreign exchange reserves – in the short, medium and long terms. This apart, while in Delhi, Solih and his team, including Foreign Minister Ahmed Shahid, also met with captains of the Indian industry as their first major engagement in the Indian capital on arrival, and invited them to invest in the country.

Investor concerns?

Solih implied that the $ 800-m Indian investment-commitment was not for India to dump on Maldives, or the latter to draw at will (divert elsewhere, say, for revenue expenditure or whatever). Specific investments would be made on projects cleared by the Maldivian authorities, he clarified. Implied, India, on its part, may have to undertake ‘due diligence’ about the feasibility of individual projects and undertake periodic work and financial audits, without interfering with Maldivian decision-making and implementation processes.

However, given the India-Maldives investment equations over the past decade, the two nations may have to create institutional mechanisms to de-politicise the processes. In the absence of such a mechanism, swift and changing domestic political conditions had badly impacted Indian investments, including massive private investments, and ended up negatively affecting larger bilateral relations.

The Maldivian government of then President Mohammed Nasheed, Solih’s boss still in the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), mishandled ‘la affaire GMR’ through the nation’s infant ‘democracy Parliament’ during his shortened tenure, 2008-12. For reasons best known to them, the Indian infrastructure giant also handled the ‘political due diligence’ part, as President Yameen observed, before giving them the marching orders for good.

Advisory cell

Big Indian investors may still be wary of investing in Maldives, given the ‘GMR experience’ as is understood and also those of others. This is also true of other neighbourhood nations like Sri Lanka. Under the previous Manmohan Singh Government, New Delhi made out a policy of encouraging the Indian private sector to chip in big to aid and assist the neighbourhood nations alongside the Indian Government.

Now with the experience gained from such a course, the Government may have to consider creating an advisory wing of some kind, to guide all stake-holders – and protect larger Indian interests, both political and strategic – in the end. Working in close tandem with the Indian missions overseas and also the infrastructure departments in the know of things, such a cell should also work closely with prospective Indian investors, and delineate touchy areas and risky investments, with full knowledge of the local conditions.

In this context, President Solih’s reiteration, both in New Delhi and back home in Male, that the Indian aid would not worsen the Maldivian debt situation should silence critics of his government in the country. With Parliament elections due in April 2019, where the odds on paper are on even, knowledgeable Indian investors may want to wait-and-watch, before taking a deeper plunge.

In this, it may be the political and moral responsibility of President Solih to ensure that his party’s commitments to the nation ahead of his election are held. The vagaries of Maldivian politics is still such that the MDP’s open post-poll attempts to thwart the purportedly continuing four-party ruling coalition in the run-up to the parliamentary elections will have greater consequences for his leadership’s global standing and credibility. It would be more than MDP’s electoral gains in the short run.

‘No’ to foreign bases

Early media reports on New Delhi aid package had spoken about Maldives granting a military base to India, as if in return. Foreign Minister Shahid, who negotiated the current deal during his maiden official overseas visit to New Delhi a fortnight earlier, lost no time in denying it outright. President Solih, both in Delhi and later in Male, reiterated the official Maldivian position that there was no question of granting any military facility to any country.

It is another matter that after Solih becoming President, an American official team from Washington called on him in Male, and committed a $10-m aid. This included a component for training Maldivian military personnel. However, the American aid too seems to be aimed at reaffirming the global commitment to Maldivian democracy, as reiterated by Solih’s election, against incumbent Yameen.

The other aspect is for the world to help Maldives minimise its dependence on China, at least from now on. India has begun playing its part, since. In doing so, New Delhi also seems to have retaken its position that South Asia is India’s ‘traditional sphere of influence’ – for its western allies to give up their continuing Cold War era constructs, but with new interpretations, twists and turns.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV