At a time when Muslim brethren in neighbouring Sri Lanka continues to be agitated over their government’s decision not to let their Covid-19 dead buried, as is the religious custom, but only cremated, a public discourse is on in Maldives over the decision to let those Sri Lankan dead buried in the country. Going by media reports, a purported majority of Maldivian religious scholars are in favour of letting the Sri Lankan Covid dead buried in their country.

Trouble started in Sri Lanka when, in the early weeks of the pandemic, the nation’s health authorities reportedly advised the government of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa not to let the Covid dead of any community buried, as contaminants could pollute underground waters and cause further escalation on land. Not only Muslims and Christians, but even a section of the majority Sinhala-Buddhist community bury their dead, but there is no hard and fast rule among them, as is the case with the other two religious’ denominations.

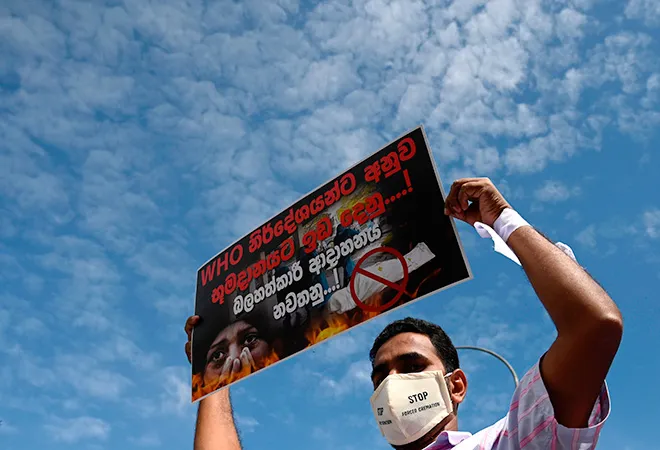

The Sri Lankan government’s decision became a hotly-contested political issue after the World Health Organisation (WHO) cleared burial as a safe procedure for disposing of Covid dead. With the result, Islamic and Christian nations across the world have been burying their dead. But the Sri Lankan government is unbending. In the light of last year’s ‘Easter Sunday serial blasts’ involving some Muslim perpetrators, and the post-war Sinhala-Buddhist nationalists’ wanton attacks on Muslim establishments and places of worship, they see a state-sponsored design to marginalise the community even more.

Offering solace

The Maldivian discourse on burying the Sri Lankan Covid dead assumes significance in this context, considering that the archipelago-nation is exclusively a Sunni-Islam nation, as mandated by a democratic Constitution. Questions have been raised in both countries about the wisdom of the Sri Lankan government decision, despite the WHO clearance for burial, especially after Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa recently declared that they would approve Covid vaccines on the island only after WHO approval.

In the context of their government’s perceived ‘double-talk’ on WHO approvals on Covid, Muslim community leaders in Sri Lanka apprehend further trouble for them all after the next round of decennial Census, pointing out how trouble for them started/revived after the post-war census, where their numbers had registered a substantial rise. Indications were that Muslims were inching towards becoming the nation’s second largest ethnicity after the Sinhala-Buddhists over the coming decades, if not already.

In a tweet announcing Maldives President Ibrahim Solih’s decision to let Sri Lankan Covid dead from the Muslim community buried in Maldives, Foreign Minister Abdulla Shahid said it was “based on the close long-standing bilateral ties. This assistance will also offer solace to our Sri Lankan Muslim brothers and sisters grieving over the burial of loved ones.” Earlier, former minister and leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC), Rauff Hakeem, submitted a memorandum to Umar Razzaq, the Maldivian High Commissioner in Colombo, outlining the “stance of the country’s Muslim community, which seeks to bring an end to discriminatory policies.” Hakeem highlighted how Sri Lanka was the only country to deny Islamic burials and how the decision was in “sharp contrast to the recommendations of the world’s leading scientific and medical communities.”

However, no Muslim politician in Sri Lanka had bothered to let the predecessor government, of which they were a part of, to publicise detailed census figures, which the post-war regime of President Mahinda Rajapaksa had held back.

Today, the Maldivian discourse, thus, centres around the immediate assistance that the nation could offer to their Muslim brothers across the Ocean, and the long-term consequences of the Sri Lankan government decisions viz a vis the island’s Muslim population.

Precarious locus standi

The Maldivian community is also equally aware of the precarious nature of their locus standi in the matter, especially vis a vis the nation’s greater dependence on Sri Lanka in economic terms, and otherwise too. Apart from the bilateral trade, on which the Maldivian economy and daily living depends, apart from the imports from India, many Maldivians have a second home in Sri Lanka. The links go back by century, and the people-to-people contact increased through the last century, especially after the tourism-centric Maldivian economic boom.

Many Maldivians have a second home in Colombo or elsewhere in Sri Lanka, especially for their children to get what tantamount to the best of school education in South Asia. It had begun with the Maldivian government of Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir — who later became the President — who had directed the nation’s Trade Office in Colombo to play guardian to school children, sent for secular education in Anglicised school.

The scheme continued vigorously, at least until the archipelago’s government-run school increased in numbers and began adopting the British Cambridge scheme and curriculum, under successor Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. However, the number of Maldivian families staying in Sri Lanka, and camping in south Indian cities of Bengaluru (Karnataka State) and Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala) has only increased, as recently-affluent families became alive to the possibilities, and could also afford to maintain a business office and/or home there.

There is also a flip side to the Maldivian position on burying the Sri Lankan Covid dead, though unaired in public. Islam deems it a dishonour and sacrilege to put a knife on the dead. Hence, the bodies of Maldivian dead from accidents, murders and suicides are being air-lifted to Colombo, for the legally-required post mortem examination. For the same reason, an Indian education entrepreneur keen on opening a medical school on an uninhabited Maldivian island, for dollar-paying overseas students, with certain percentage reserved for locals, could not proceed in the matter.

Maldives also requires Sri Lankan assistance in terms of long-distance overseas travel, for both its leaders and common people. There is also a lot of cooperation between various law-enforcing agencies in the two countries, which needs to go on unhindered, in terms of curbing drug-smuggling across Oceans and nations, for which the two island-nations have become an international hub. At the height of the ‘ISIS war’ in Syria, then Maldivian government of jailed President Abdulla Yameen counted on Sri Lankan authorities to turn in misguided nationals who were smuggling themselves or others to the war-front, at times with their unsuspecting wife and infant children.

Islamic brotherhood

Participating in the social media debate on letting Sri Lankan Covid dead buried in Maldives, former President Gayoom, who is also an acknowledged religious scholar who studied theology in Al-Azhar University, Egypt, tweeted against the government decision. The government was not obligated to do so under religious tenets, he said in two tweets, adding that such a course would also ‘support mistreatment’ of Muslims in Sri Lanka.

From among other religious scholars who backed the government’s decision, the likes of Dr Mohamed Iyaz also cited assistance to “Sri Lankan Muslim brothers who are being ill-treated” in their country, as justification. “In my opinion, I think, it is an obligation of the Maldives as an Islamic nation to assist Sri Lankan Muslims,” Dr Iyaz said, as if to contesting President Gayoom’s opposition to the move.

Dr Iyaz said that “Maldives should assist Muslims everywhere around the globe,” and added that the move would also bring relief to the thousands of Maldivians living in Sri Lanka. Citing scriptures, he said “the best that can be done to forbid the cremation of Muslims, is by bringing their bodies to the Maldives and burying them according to the Shariah.”

Dr Iyaz did not mince words when he claimed, “If that (burial of Sri Lankan Muslims in Maldives) is not arranged, Maldivians would also be cremated under the power of the Buddhists of Sri Lanka…. In Sri Lanka, Muslims are cremated because the Buddhists have power over the Muslims.” It is thus in the best interest to prevent the cremation of bodies by moving the bodies of the deceased from one location to another, even if the custom states that the dead are to be buried as soon as possible, he added.

Taking what reads like a political position, Sheikh Ali Zaid, another religious scholar said that “some of the Opposition would point out the vileness of the government if they had not assisted the Muslims of Sri Lanka. Now that they are assisting, it is being disapproved.” Likewise, Sheikh Ilyas Hussain, another scholar, too, has backed the government decision.

For his part, Islamic Minister Dr Ahmed Zahir said that the burial arrangement of Sri Lankan Muslims in the Maldives was a good deed and an important one at that. Other scholars too have also described the move which will go down as a benevolent page of the history books.

Tri-nation consequences

Independent of scholarly views and public sentiments in Maldives over burying the Sri Lankan Muslim Covid dead in their country, Colombo’s decision of the kind could have medium and long-term consequences for the future, in terms of collective security of the two nations. It could also involve their common Indian neighbour. Sri Lanka and Maldives especially have to be aware of and alive to the possibilities.

In the midst of the Sri Lankan controversy, the National Security Advisors (NSA) of the three nations met in Colombo to upgrade their ‘maritime security cooperation’ arrangement into one on ‘maritime and security cooperation,’ and cleared a secretariat in Colombo to coordinate their initiatives and efforts. It is an acknowledgement of the multifaceted nature of security threats to the three nations and their shared seas, including those pertaining to internal security issues.

Threat of religious terrorism links all three of them, as has been the case in the past. In 2015, Malaysian investigators shared with their Indian counterparts a plot for three Maldivians to bomb the US and Israeli consulates in south India. In the previous year, security agencies in southern Tamil Nadu apprehended a Sri Lankan national before emplaning for Colombo, to meet with his Pakistani ISI handles, posted in the nation’s Colombo Embassy.

The involvement of Maldivian radicals in the ISIS war in Syria, with some of them dying for ‘the cause’ and Sri Lankan Muslims involved in what the government of the day said was a home-made act of ‘Easter blasts,’ the stakes are too high for the Indian Ocean neighbours. In context, further provocation in Sri Lanka, which was earlier confined to Sinhala-Buddhist zealots but has since upgraded into what will be mischievously misinterpreted as a State-sponsored act, can have very serious consequences, not only for the island-nation, but also for the other two and their shared waters.

This could include avoidable future strains in bilateral and trilateral relations, as the possibility of involvement of religious terror groups from either of the other two nations cannot be ruled out, and yet with the victim-nation blaming or at least suspecting the other two of collusion. They have an example in the Sri Lankan Easter blasts, where a section of the nation’s political and strategic community pointed fingers at India, when the latter could be ‘blamed’ only for repeatedly alerting counterparts in Colombo about the impending catastrophe.

This article originally appeared in ORF South Asia Weekly.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV