History, once again, is under contest in India – a relatively young country at 70. Education and official history in particular has been an important instrument for nation-states to shape the collective memory of its people. No doubt that the emergence of nation-states have been concurrent with rise of mass schooling.

At the outset, education fulfilled nationalistic aim for the nation-states.

Official versions of history were created in the 19th and 20th centuries to create glorified images of their own nation and the ruling groups while undercutting the other nations and minority groups. Even geographical features like mountains, rivers and oceans would be used to whip up nationalistic sentiments.

It was only after World War II, the world came to understand the perils of narrowly defined nationalism, propagated through education. The national curriculum, thereafter, was broadened to incorporate foreign cultures and languages.

Knowing it all well that history can be used to shape national identity of any population, the Indian right is making allout efforts to foster a myopic vision of India that is undergirded on obliterating the contribution of a particular community to the country’s culture and building from public memory.

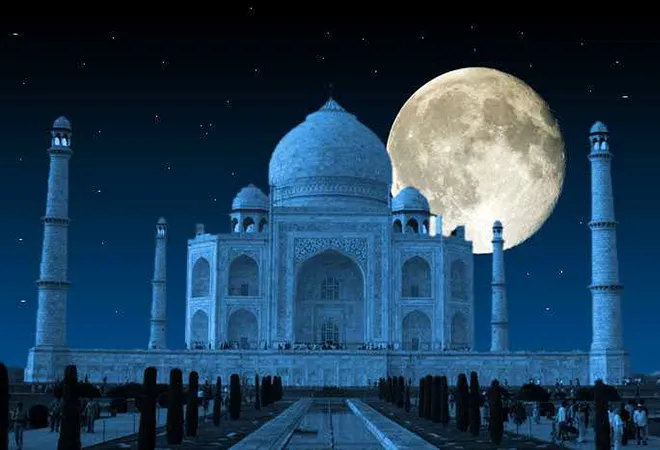

So, according to the revisionist historians, Taj Mahal was not built by Shah Jahan and was previously a Hindu Temple; Rajput King Maharana Pratap no longer is known to have lost the battle of Haldigati to Emperor Akbar and; mythology is being given historical legitimacy with astonishing feats like inventions of aircraft flying in any direction been attributed to Hindu geniuses.

Warnings of liberals and seculars about the dangers of India heading to become ‘Hindu Pakistan’ seems a bit abstract, unless one has read the books of Pakistan curriculum themselves and correlate it with the problem of religious intolerance, fanaticism and violence festering in the society. Read for example the Introduction to Pakistan Studies for Secondary, Intermediate and GCE ‘O’ Level. The historical background of the country starts with lessons on Islam. The history of Pakistan in the book begins with attack on India by Muhammad Bin Qasim in 711 AD. There seem to be disconnect from the multi-religious and multi-cultural past of the region that now forms Pakistan.

The book talks about how Islam impacted society, culture, governance and architecture of “Hindus” of India; and leave out what its adherents took from the others in return.

The reign of Emperor Ashoka and the popularity of Buddhism during his rule is conspicuous by its absence in Pakistan’s history books. The book also seek to glorify the Babar’s victory as a golden era for Islam in the sub-continent and hence for Pakistan. The fact that Babar defeated another Muslim ruler Ibrahim Lodhi to take reins of Delhi in his hands has been glossed over. The kings and emperors of the time did not shy away from fighting their co-religionists for the sake of their kingdoms and empires, but context is the first casualty at the altar of refashioning the history to suit the ideology of hatred.

Besides this, there is vilifying of the others. The role of Sikhs and Hindus in the public life has been completely wiped out from the history of Pakistan. The only role that the young Pakistani students have read of Hindus and Sikhs playing is being butchers of Muslims during 1947 partition. A balanced approach that the both sides of border saw mayhem and bloodshed would not suit the hate narrative being spawn to nationalise the population of the newly-built country. A false binary of Hindus and Muslims is being established, discounting the fact that Muslims of a region in the sub-continent will have more similarities to his Hindu co-habitant than with a Muslim in a faraway land. The youngsters of the country cannot be faulted for having a uni-dimensional view of the country.

The right in India might detest Pakistan, but they do not shy away from taking a leaf out of their history books. Indian educational curriculum is intended to become more exclusivist and divisive. The fundamentalisation of Indian textbooks has begun as the books are pruned of any positive references to Muslims to revive the pride of the “Hindu” – ‘who has been victimised for centuries’. This self-image of victimhood serves greater purpose as it paves way for pinning the blame of all evils in the society or country on the other side (Muslims/Pakistan) or a third party (the Britishers).

The actions of Mughal rulers destroying temples or other places of worships and forcible conversions will be used out of context to show them only in poor light. The misdemeanours of the Hindu rulers will be concealed through mere omission.

True to its narrative, the right-tinted books portray Hindu as the inheritors of the legacy of India, whereas Muslims are the invaders and thus heralded the decline of the Indian culture.

Just as across the border, the history book on this side lay the blame of partition squarely at the doorstep of M.A. Jinnah rather than objectively studying it. Muslim League dominates the landscape of Indian Freedom struggle as the villain, while the role of Hindu communal groups has been muted.

Detractors might term it again a red herring sounded by the liberals and seculars, but as James H. Williams and Wendy D. Bokhorst-Heng said in ‘(Re) Constructing Memory: Textbooks, Identity, Nation and State’ that textbooks are a repository of facts, figures, dates and seminal events that a society want its children to learn. Textbooks also frame narratives that “describes how things were, what happened and how they came to be the way they are now. A group’s representation of its past is often intimately connected with its identity – who “we” are (and who we are not) as when who “they” are”. So textbooks do provide a window to a nation’s hidden social and political curriculum; and changes in educational curriculum are often an attempt by the state to counter the challenges to its legitimacy.

So textbooks do provide a window to a nation’s hidden social and political curriculum; and changes in educational curriculum are often an attempt by the state to counter the challenges to its legitimacy.

For long, Indians have been identifying themselves with the plurality in the country, but if they do not resist the attempt to identify the country with a particular religion, the idea of Unity in Diversity would be a thing of past. And, it is not sure if it would even be part of the new history books. In the times of globalisation and increased intermingling between people of different communities, nations cannot define themselves without knowing and appreciating the others.

Ritu Sharma has been a journalist for nearly a decade, covering defence and security issues. She has done her Masters in Conflict Studies from Germany.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

History, once again, is under contest in India – a relatively young country at 70. Education and official history in particular has been an important instrument for nation-states to shape the collective memory of its people. No doubt that the emergence of nation-states have been concurrent with rise of mass schooling.

History, once again, is under contest in India – a relatively young country at 70. Education and official history in particular has been an important instrument for nation-states to shape the collective memory of its people. No doubt that the emergence of nation-states have been concurrent with rise of mass schooling.

PREV

PREV