This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

After the Second World War, there was widespread fear amongst the US servicemen that peace would mean job losses and that the end of wartime military spending would send the US economy back into the great depression. In response, the US administration brought the GI Bill of Rights, also known as the servicemen’s re-adjustment act in 1944 that provided education, job training, hiring privileges, unemployment benefits, low-interest loans for housing and education, medical care, and disability benefits. Later during the Cold War, the USA addressed every recession with an increase in military spending. The motive was to restore economic growth, but it was justified by geopolitical tensions. Consequently, peace and anti-bomb activists in the USA realised that jobs and economic prosperity must be ensured to end the arms race. In the 1970s, peace activists reached out to the trade unions for planned conversion to a peacetime economy. The oil, chemical, and atomic workers unions proposed that workers whose jobs were threatened by disarmament should receive support similar to the GI bill of 1944.

In the 1990s, the idea was revived to provide financial support and opportunities for higher education for workers displaced by environmental protection policies, primarily in the USA. Trade union leaders demanded that a superfund for cleaning up toxic waste must be complemented with a superfund for workers in toxic sectors. Given the negative connotations associated with the term ‘superfund’, it was rechristened ‘just transition’ in 1995 and the just transition alliance between environmental groups and trade unions was formed in 1997. The basic concept behind the just transition was workers in sectors labelled toxic should not be asked to pay a disproportionate tax, in the form of unemployment, to achieve the goals of environmental protection.

Though some trade unions are strong enough to resist the prospect of privatisation and job losses in India, the link between environmental movements and trade unions is weak. This undermines the case for just transition for workers in sectors that will be affected by Indian carbon mitigation policies.

Just Transition in Climate Conventions

Section 8, Article 4 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 1992 called on parties to give full consideration to what actions are necessary under the convention, including actions related to funding, insurance, and the transfer of technology. These actions were discussed to meet specific needs and concerns of developing country parties arising from the adverse effects of climate change and/or the impact of the implementation of response measures, especially on countries whose economies are highly dependent on income generated from the production, processing and export, and/or on consumption of fossil fuels and associated energy-intensive products. The preamble of the Paris Agreement on climate hange, drafted in 2015, observed that the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities must be taken into account. The just transition declaration, agreed at the at UN Climate Change conference in Scotland (COP26) in 2021, recognised the need to ensure that no one is left behind in the transition to net zero economies—particularly those working in sectors, cities, and regions reliant on carbon-intensive industries and production. None of the less wealthy developing countries, including India are signatories to the Declaration.

Resettlement and rehabilitation in India

Most of the recent reports on just transitions in India emphasise considerations related to overall improvement in energy access, difficulties in phasing out coal in India and the need to integrate development with decarbonisation. Case studies of coal phase out plans in countries like South Africa and Indonesia are discussed drawing out lessons for India. Though the issue of who will pay for the transition is addressed in some of the reports, most argue that the levelised cost of energy (LCOE) of renewable energy (RE) is very low and the energy transition will effectively be costless. The suggestion is that the energy transition will effectively pay for the social transition with new jobs and also underwrite energy access with low priced RE. This assumption may not be accurate as the overall system costs are higher for RE (managing intermittency, uncertainty with back-up storage or alternative generation, transmission from production to consumption centres). How the effects of higher energy prices for consumers (visible in European countries with high share of RE) and energy-intensive industries will be addressed is rarely discussed in reports on just transition in India. Other analysis offering suggestions for a just transition for India argue that the overall benefits outweigh the costs. Apart from emphasising that RE is cheaper and that the RE industry will create millions of new jobs, cleaner air is offered as a value comparable to livelihoods and coal phase out is presented as a means to eliminate organised crime in poor mining districts. In the solar sector, an entry level contract employee with a graduate degree in engineering is paid wages that are lower than average wages<1> for unskilled labour in India. This is not job creation, but abuse that partly underwrites low tariff solar electricity.

While most of the longer reports are thorough with empirical analysis and detailed normative conclusions, few discuss the history of India’s earlier transition from an agrarian to an industrial economy (though yet incomplete) and the low bar it has set for rehabilitation of those who have paid a disproportionate tax for industrialisation, in the form of unemployment or loss of land and livelihood. In all probability, this low bar is likely to have a stronger influence on how social externalities of decarbonisation are handled in India than the ideologically high bars borrowed from wealthy economies.

Resettlement and rehabilitation (R&R) of project affected people or families (PAP/PAF) is how India has historically interpreted and implemented the idea of a just transition. Most rigorous accounts conclude that the legal and human rights of 35,000 families directly affected by the Sardar Sarovar dam project were sacrificed for the “national good”. There is no dearth of documentation of a number of other examples of poor implementation of R&R in large industrial projects. India’s land acquisition laws, including the most recent law, offer procedural legitimacy to the act of taking land from people against their will for the greater “public good”. A striking illustration is offered by the Bhadla solar park in north-western Rajasthan and Pavagada park in southern Karnataka states. Both are among the world’s biggest, with a combined generating capacity of 4,350 megawatts peak (MWp). In both sites’ jobs, hospitals, schools, roads, and water were promised in exchange for the land that local communities used for sustaining livelihoods. Though, the solar projects have come up and are celebrated worldwide for their contribution to decarbonisation, almost nothing of what was promised to local communities have materialised. In both examples the official conclusion was that PAFs were adequately compensated under the respective R&R packages. In the case of Sardar Sarovar, the report of an official committee set up to investigate the plight of PAFs concluded that there were no compromises in dealing with social externalities of the dam project. The Supreme Court endorsed the conclusion in favour of industrialisation.

Interestingly a plan for a “socially fair” shift away from coal, described as India’s first (possibly acknowledging that India’s past transitions were socially unfair) is about to be implemented with World Bank assistance in certain districts of Eastern India where mines have been shut. The timeline for the "just transition" project is estimated to be about eight years and the cost at least US$1 billion. Even if successful, it may be difficult to replicate and scale up a World Bank-funded model across the country. There is no history of large-scale re-education, training, and rehabilitation of workers who have lost their jobs or land, especially those at the bottom of the employment and economic pyramid. Most importantly the concept of rights rather than justice is invoked in addressing livelihood losses in India. A right, considered a privilege offered to the citizens by the state, can be abandoned in the larger interests of the state.

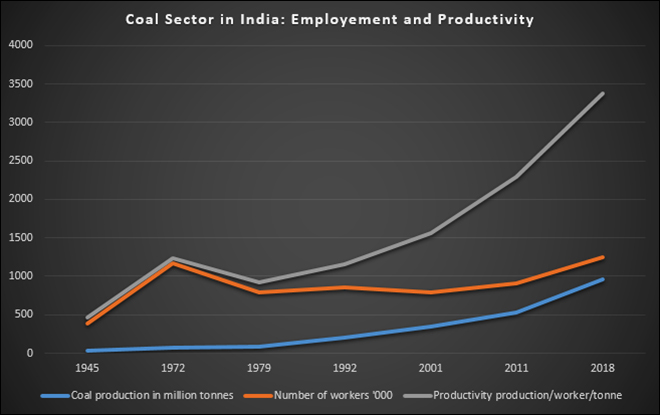

Source: For 1945-2011, Sanhati, 2011. Overview of Coal Mining in India: Investigative Report from Dhanbad Coal Fields; for 2011-2018, Coal Controller of India

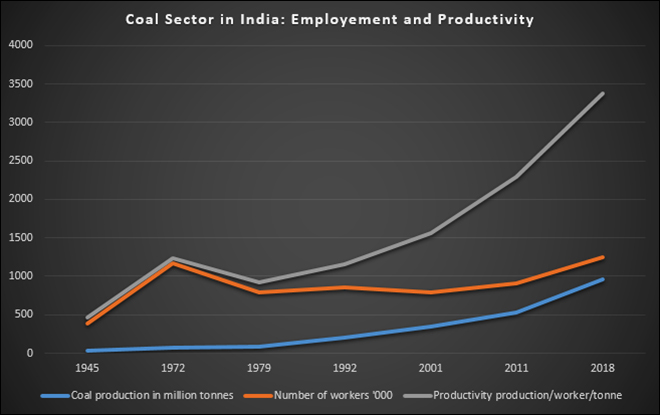

Source: For 1945-2011, Sanhati, 2011. Overview of Coal Mining in India: Investigative Report from Dhanbad Coal Fields; for 2011-2018, Coal Controller of India

<1> Personal interview and discussion

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV