This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

In April 2022, Niti Aayog, the in-house think tank of the Indian government, released a draft policy for battery swapping (BS) for two and three-wheelers. The vision of the policy as stated in the draft is to catalyse the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) by improving the efficient and effective use of scarce resources such as public funds, land, and raw materials for advanced cell batteries for the delivery of customer-centric services. The policy goals are to (1) promote swapping of batteries with advanced chemistry cell (ACC) batteries to decouple battery costs from the upfront costs of purchasing EVs, thereby driving EV adoption (2) offer flexibility to EV users by promoting the development of battery swapping as an alternative to charging facilities (3) establish principles behind technical standards that would enable the interoperability of components within a battery swapping ecosystem, without hindering market-led innovation (4) leverage policy and regulatory levers to de-risk the battery swapping ecosystem, to unlock access to competitive financing (5) encourage partnerships amongst battery providers, battery (original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and other relevant partners such insurance/financing, thereby encouraging the formation of ecosystems capable of delivering integrated services to end-users (6) promote better lifecycle management of batteries, including maximizing the use of batteries during their usable lifetime, and end of life battery recycling.

The draft presumes the success of BS which in turn is expected to resolve larger issues at the other end of the value chain such as domestic manufacture of ACC batteries and production of EVs.

The provisions in the draft policy address some of the challenges specific to the battery and EV industry. However, the draft presumes the success of BS which in turn is expected to resolve larger issues at the other end of the value chain such as domestic manufacture of ACC batteries and production of EVs. It also expects BS which is only a small part of the EV ecosystem to facilitate the decarbonisation of mobility in India.

Battery Swapping

The value of BS lies in the fact that separating the price of the electric car from its costliest part, the battery will make it attractive to the customer. BS can reduce range anxiety and uncertainty as batteries can be chosen flexibly based on their size and can either be purchased or rented on a monthly basis. Also, the services could be based on a monthly subscription according to the required amount of energy, offering flexibility to the customer.

The batteries in all EVs have to be charged with electricity periodically. Apart from stationary charging (normal or fast) with a cable which is the most dominant model globally, static and dynamic conductive and inductive technologies are also available for charging. Under the BS model, the discharged battery inside an EV is exchanged for a charged battery from outside the EV in a BS station (BSS). Ideally, the BSS would store thousands of standard certified batteries with people (or robots) to carry out the swapping in a few minutes.

BS is not new. The German company Mercedes-Benz tried it in the 1970s but it did not succeed. The Israeli company Better Place reintroduced it in 2007 but it went bankrupt. The American company Tesla tried it in 2013 with a modular design for its car. Tesla then opted for its own proprietary cable-based charging system and a business model that integrated cars and charging.

Apart from stationary charging (normal or fast) with a cable which is the most dominant model globally, static and dynamic conductive and inductive technologies are also available for charging.

The Indian BS initiative appears to be following China which is currently seeing a revival in the sector. The Chinese EV makers tried BS in the early 2010s, but it did not take off. High cost of batteries and that of BS, lack of standards, lack of openness and divergent technical and economic interests amongst key stakeholders, objections from car manufacturers to opening up their vehicle structure and lack of government support are amongst the reasons cited for the failure of the Chinese early experiment with BS. The revived BS model in China addresses these concerns. In 2020, the Chinese central government included BS technology in the ‘national new energy vehicle development strategy 2021 to 2035’ and included battery-swapping in the list of the ‘new infrastructure construction campaign’. In early 2021, there was 562 BSSs operative in China, providing service to taxis, online car-hailing vehicles, private passenger vehicles and business vehicles. More than 100,000 cars have been sold in China with battery-swapping systems.

Issues in Battery Swapping in India

The draft policy offers three arguments to justify the focus on battery swapping in the two and three-wheeler segments. First, two and three-wheelers account for 70-80 percent of vehicles in the country; second, the two and three-wheeled electric vehicles are cost-competitive with an internal combustion engine (ICE) based vehicles and third, lighter batteries used in electric two and three-wheelers are easier to swap. These assumptions need to be qualified. The high share of two and three‐wheelers in India’s vehicle fleet is the reason why personal vehicles (cars) account for only 18 percent of its overall transport emissions. This is much lower than in many other countries; in the United States, for example, passenger cars account for 57 percent of total transport emissions. Two and three-wheelers may account for 80 percent of vehicle stock, but they account for only about 20 percent of transport energy consumption and roughly 18 percent of transport emissions. Even if all two and three-wheelers are electrified the reduction in emissions is not likely to be significant.

The cost competitiveness of two and three-wheelers on the measure of the total cost of ownership (TCO) rests on the fact that high taxes on liquid petroleum fuels make these fuels uncompetitive against any fuel including gas. These taxes provide a large source of revenue for the government. More than 90 percent of EVs on Indian roads today are low-speed electric scooters (less than 25 kilometres per hour ) that do not require registration and licenses. Almost all electric scooters run on lead batteries to keep the prices low. The absence of government control is the primary driver of the industry, and it is unlikely that these users are longing to use swappable lithium-ion batteries that will put them under government regulation.

The high share of two and three‐wheelers in India’s vehicle fleet is the reason why personal vehicles (cars) account for only 18 percent of its overall transport emissions.

The BS policy expects major car companies to share the technology around batteries (or any technology) that goes against standard commercial norms. In the traditional car industry, some compatibility exists only in minor devices such as the cigarette lighter power supply and the valve stem for tires. Compatible battery design and technology enforced by strict government mandates are likely to inhibit rather than facilitate battery manufacture. Interchangeable batteries would also mean a large quantity of scarce and expensive resources such as lithium and cobalt stagnating in BS centres.

In 2020, the Ministry of Road Transport allowed two and three-wheeled EVs to be sold in India without the batteries paving the way for battery swapping. A handful of BS providers have since set up operations in India with the most concentrated in Delhi which has the largest private vehicle population. Sun mobility operates in over 10 cities. But BS has not taken off on the scale it has in China. The large investment required for BS station construction, the high financial cost of batteries in the swapping stations, battery depreciation, difficulty in achieving unified standards, overlap of the division of responsibilities, limited space for station construction and safety concerns are some of the issues inhibiting growth of BS in India. The scale of EV sales, EV charging facilities and BS services are orders of magnitude lower than that of China. India is far behind China in the manufacturing of EVs and batteries. Most importantly the Chinese government’s ability to bring together a diverse set of stakeholders to meet the strategic goal of leadership in EV and battery manufacture is difficult to replicate in India. The policy on BS is one small step in facilitating the adoption of EVs. It is a necessary but not sufficient condition to make a giant leap towards decarbonising mobility in India.

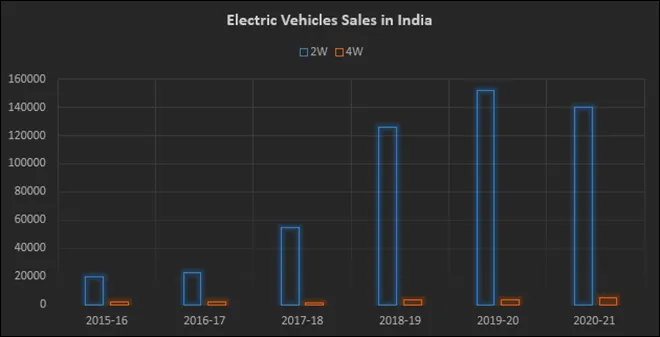

Source: Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles

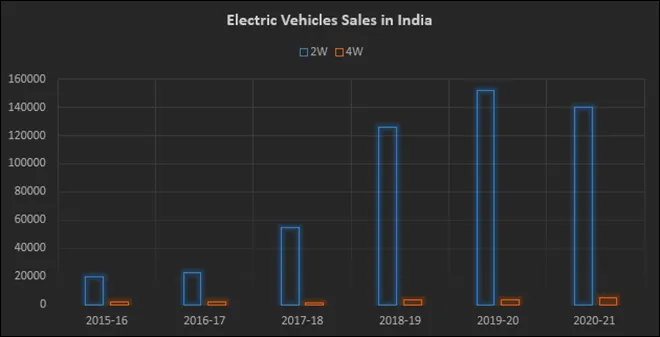

Source: Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV