This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

The twenty-first century economic growth agenda needs to be reframed to ensure that cleaner production and consumption processes — goal 12 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — go hand in hand with pursuing dignified sustainable living for all<1>. The impacts of COVID-19 have made the basic needs for human wellbeing even more clear. Energy and water have emerged as the top needs, and are connected to several SDGs, including human health. Approximately 50 percent of the global population does not have access to the basics needed for dignified living, with most of the deprived living in South Asia, East Asia and Africa.

The 2021-2030 decade will be a landmark one for multiple reasons. During this period, an otherwise politically-fragmented global order has to deliver the 17 interconnected SDGs, without any region or people being excluded — a collective political promise made by all world leaders in 2015. Two more monumental agreements for global cooperation in developmental action were reached in 2015, to be accomplished during this decade — the Paris climate agreement to keep global warming well below the 2°C above pre-industrial levels<2>, and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction<3>. These international frameworks aim at shifting collective global policy priorities for developmental action to the sustainable development path by 2030<4>. Although 2020 will be remembered as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, it also marked the 75th anniversary of the UN’s inception and the 30th anniversary of the launch of international climate negotiations, and was also set as the year from which carbon dioxide emissions’ growth should start reducing through global climate action (SDG 13)<5>.

The impacts of COVID-19 have made the basic needs for human wellbeing even more clear. Energy and water have emerged as the top needs, and are connected to several SDGs, including human health.

The pandemic is expected to directly adversely impact the fulfilment of SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing), SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities)<6>. The global economic lockdown necessitated by the pandemic led to an increase in poverty and hunger, job losses, loss of human life, reduced access to educational services due to the digital divide, and the loss of income<7>. If indirect impacts are considered, COVID-19 will likely cause a setback to all the other SDGs as well, since it has, for instance, led to increased domestic violence<8> and greater difficulty in accessing clean water<9>. There is growing literature on how to recover better from COVID-19 so that the developmental promises of 2015 can still be kept<10>. The global stimulus of US$ 12 trillion<11>) following the pandemic is providing some hope for building back better, but doubts have been expressed about how much of this will be spent on priority sectors such as the key SDGs, including climate action<12>.

What economic recovery growth path each country adopts through the rest of this decade will be extremely important. Every choice made to meet developmental aspirations will matter, impacting the climate system and human wellbeing. Identifying synergies and mutually reinforcing developmental and climate actions will help countries set the best path to sustainability. Emission reduction by shutting down all economic activities should not be an option, nor is it desirable. The COVID-19-induced global shutdown of economic activity has already shown that any such disruption will mean a huge trade-off between SDG 13 (climate action) and all the other SDGs. The SDG framework provides for recovery through mutual cooperation across nations and the sharing of good practices<13>.

Emission reduction by shutting down all economic activities should not be an option, nor is it desirable.

International diplomacy has also shifted from using hard power to soft power<14>, applied along multiple dimensions such as trade relations, economic cooperation or sanctions, and developmental cooperation. The SDGs provide a broader scope for developmental diplomacy. They allow for actions that are not limited to governmental initiatives, but can also be taken by educational and cultural institutions, and individuals. Cultural diplomacy can help to strengthen and achieve multiple SDGs through the exchange of ideas and information, capacity building, scientific and business cooperation, and private and multinational investment. Art, literature, music, sports and the promotion of tourism can enhance global solidarity, partnership and cooperation during the recovery period. Soft power can play a big role in the post-pandemic recovery process, helping to avoid conflicts and stem the rise of militancy, which typically thrive amid crises.

Whether the SDGs will be achieved by 2030 will depend on what happens in developing countries like India and those in South and East Asia and Africa. To implement equity and justice, approximately 50 percent of the global population deprived of the basics must be given access to decent living standards<15>. For India, which still has around 84 million people living below the poverty line, this is a key challenge<16>. There has been much debate on what population growth in the developing countries will mean for global consumption and carbon emissions in the decades ahead<17>, with some even suggesting that the developed world must manage its consumption responsibly to counter this<18>. But this issue will need deeper analysis and further conversations<19>.

Indian soft power diplomacy and the SDG framework

Adroit diplomacy, conducted through dialogue, negotiation and other non-violent means, including the use of soft power, can influence international decisions peacefully through cooperation. Climate diplomacy and sustainable development diplomacy are emerging as major instruments in the multilevel governance architecture. International cooperation can be seen as a vertical integration in a multilevel governance framework<20>, which leads to the building of trust. At international climate discussions — from the Stockholm Conference in 1972 (the first global meet to build environmental diplomacy) to the annual Conference of Parties — India has aligned with global aspirations for multilateral actions and pushed cooperation, thus building trust with the rest of the world<21>. India’s consistent position has been that developmental deficits have to be reduced through global cooperation in technology, innovation sharing, capacity building, and the sharing of best practices (economic, environmental or social). In the past decade, India has streamlined its development partnership administration under the Ministry of External Affairs’ economic relations division<22>, with neighbouring states and African countries within its ambit.

Climate diplomacy and sustainable development diplomacy are emerging as major instruments in the multilevel governance architecture.

A key line of thinking in the post-pandemic world has been that development processes need to be more inward looking, with each country prioritising its own interests<23>. But there is an equally strong argument for global solidarity in this crisis, from vaccine sharing to providing equitable access to new knowledge, and including soft power diplomacy. Efforts are being made to identify and strengthen joint actions for economic growth and social justice without environmental damage<24>, in keeping with the SDG framework. India’s investment in infrastructure developing in Nepal, Bangladesh and several African countries in the pre-COVID-19 period, and its gestures of cooperation during the pandemic (such as through resource and vaccine sharing) are apt examples of soft power diplomacy, and meet the targets of SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing) and SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure).

The SDGs and climate diplomacy within the UN framework are providing India with new opportunities to flex its soft power through economic, developmental and cultural initiatives, strengthening the country’s position in international cooperation and peace building efforts. India’s role in managing global common resources has given its diplomats — who understand climate change imperatives and are aware of the new developmental mechanisms around adaptive and mitigative actions<25> — a new platform for international negotiations.

Sustainable development is now conditional on climate action and having robust international relations. The increasing role of information technology in diplomacy is also giving it newer dimensions. International and regional negotiations now include natural resource sharing and resource management, with close links to national, regional and developmental achievements.

Sustainable development is now conditional on climate action and having robust international relations.

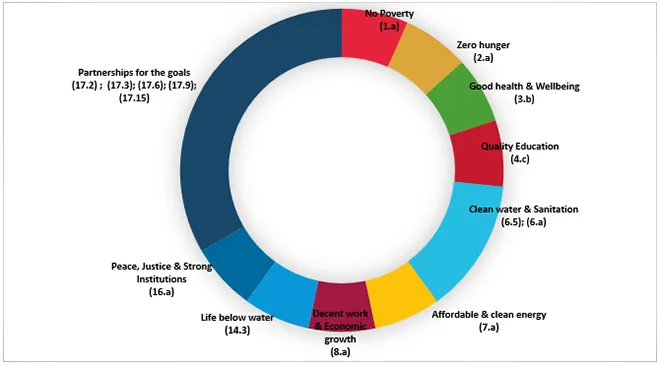

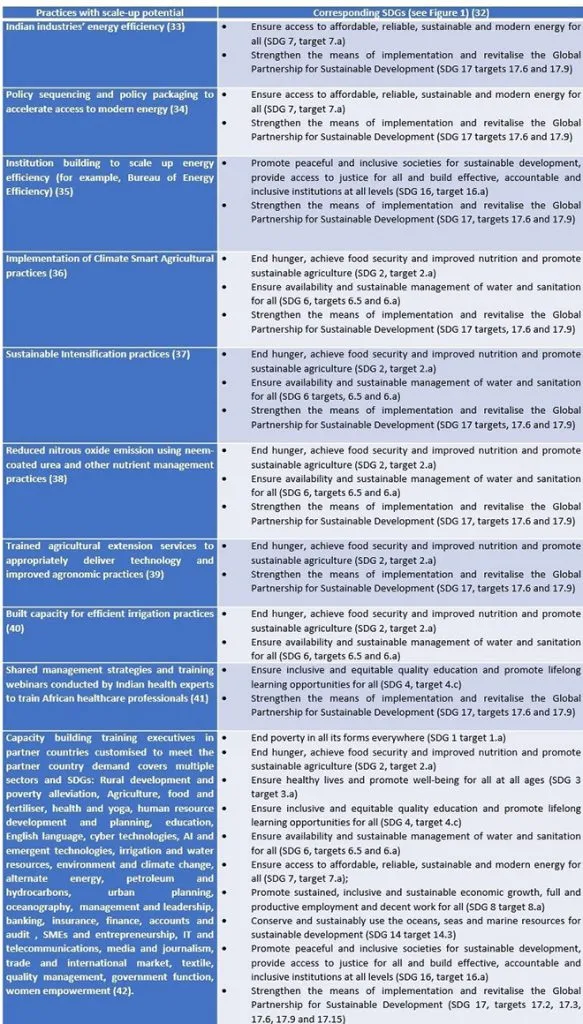

International cooperation within the SDG framework is possible under SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) as well as nine other SDGs: SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing), SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG 14 (life below water) and SDG 16 (peace justice and strong institutions) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: SDG Targets Related to International Cooperation

Source: Authors’ own

Source: Authors’ own

Note: Colour codes are the same as SDG colour code<26>. Numbers represent SDG 1 to SDG 17 and alphabets associated with the numbers represent targets under each SDG (see table below). The larger the slice, the larger are the relative number of targets having a ‘cooperation’ dimension within a given SDG.

| SDG |

Description |

No. of targets |

| 1 |

No poverty: (1.a) Mobilisation of resources to end poverty through developmental cooperation |

1 |

| 2 |

Zero hunger: (2.a) Invest in rural infrastructure, agricultural research, technology and gene banks by international cooperation |

1 |

| 3 |

Good health and wellbeing: (3.b) Support research, development and universal access to affordable vaccines and medicines |

1 |

| 4 |

Quality education: (4.c) Increase the supply of qualified teachers in developing countries through international cooperation |

2 |

| 6 |

Clean water and sanitation: (6.5) Implement integrated water resource management by transboundary cooperation; (6.a) Expand international cooperation to developing countries in water and sanitation related activities |

2 |

| 7 |

Affordable and clean energy: (7.a) Promote access to research, technology and investments in clean energy by enhancing international cooperation |

1 |

| 8 |

Decent work and economic growth: (8.a) Increase aid for trade support |

1 |

| 14 |

Life below water: (14.3) Reduce ocean acidification through enhanced scientific cooperation |

1 |

| 16 |

Peace, justice and strong institutions: (16.a) Strengthen national institutions to prevent violence and combat crime and terrorism through international cooperation |

1 |

| 17 |

Partnerships for the goals: (17.2) Implement all development assistance commitments; (17.3) Mobilise financial resources for developing countries (including South-South cooperation); (17.6) Knowledge sharing and cooperation for access to science, technology and innovation; (17.9) Enhanced SDG capacity in developing countries by South-South and triangular cooperation; (17.15) Respect national leadership to implement policies for the sustainable development goals through development cooperation |

5 |

India can strengthen its diplomatic relations by using more sectoral scientific research outcomes in its cooperation efforts. India has two major success stories at the intersection of climate change, sustainable development and economic growth that can be scaled up in many developing countries — energy efficiency in industries and sustainable agriculture practices.

Best practice in energy efficiency

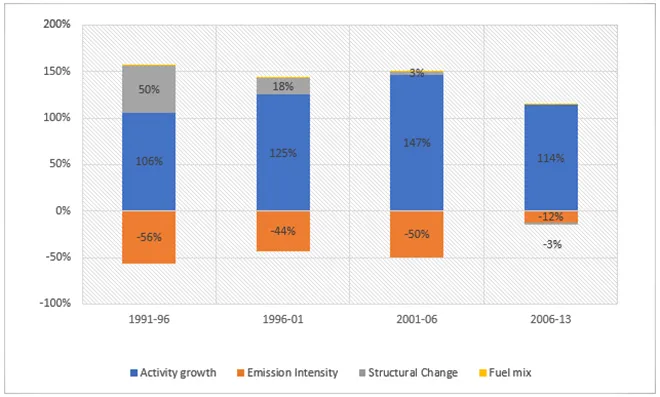

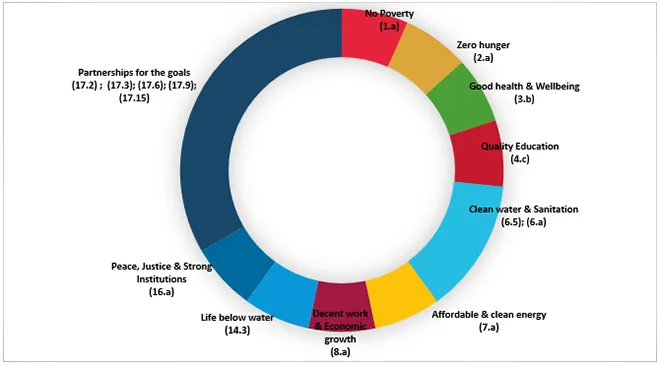

To remain globally competitive, Indian industries have been becoming increasingly energy efficient, taking advantage of technological advancements and innovations<27>. Higher industrial energy efficiency is responsible for India’s success in relative decoupling of growth from emissions<28> — achieving growth without a corresponding expansion of its carbon footprint across all sectors (residential, agriculture, transport, industry and power). Emissions are certainly rising due to growing economic activity, but structural changes and alterations in industries’ energy intensity have neutralised a major part of emission growth (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: India’s Energy Intensity (1990-2013)

Source: Adapted from Nandini Das and Joyashree Roy <29>

Source: Adapted from Nandini Das and Joyashree Roy <29>

Sustainable agriculture practices

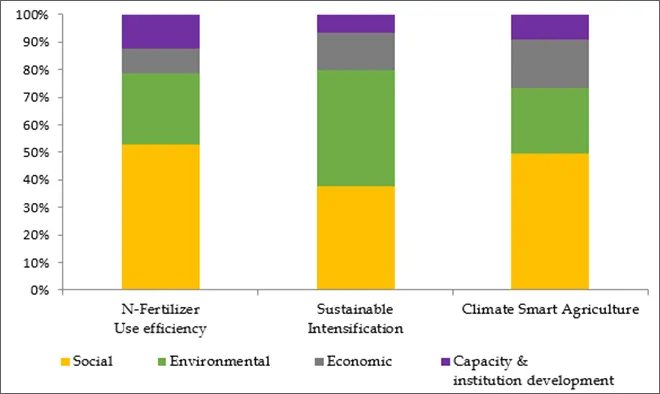

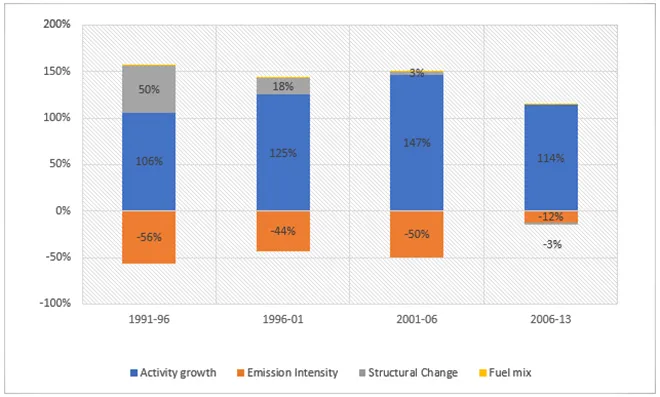

India has incorporated several sustainable agricultural practices, such as nutrient use efficiency (NUE), system of rice intensification (SRI) or sustainable intensification, and climate smart agriculture (CSA), that have wide economic, social, environmental and climate impacts. SDG benefits due to these practices have been tracked in four broad categories — social, representing SDGs 1, 2, 3, 4 ,5 and 10; environmental, representing SDGs 6, 12, 13, 14 and 15; economic, representing SDGs 7, 8, 9 and 11; and capacity and institution development, representing SDGs 16 and 17 (see Figure 3)<30>.

Figure 3: Relative Share of Different Impact Dimensions in Various Actions

Source: Adapted from Shreya Some <31>

Source: Adapted from Shreya Some <31>

With NUE, more than half the SDG net benefit (positive impacts minus negative impacts) is in the social category (52.8 percent) followed by environmental (25.8 percent); capacity and institution development and economic impact share 12.3 percent and 9.1 percent respectively. For SRI, the environmental impact is foremost at 42 percent, closely followed by the social at 38 percent. For CSA, the share of social net benefit is the highest at around 50 percent, distantly followed by environmental at 24 percent. Once these new practices are accounted for within the new sustainable development framework, development and climate goals can be achieved jointly. All these success stories stem from several factors, such as state intervention, public-private partnerships and capacity building. The negative impacts of growth can be avoided through science-based policy design, expert consultation, policy implementation, higher awareness and further capacity building programmes.

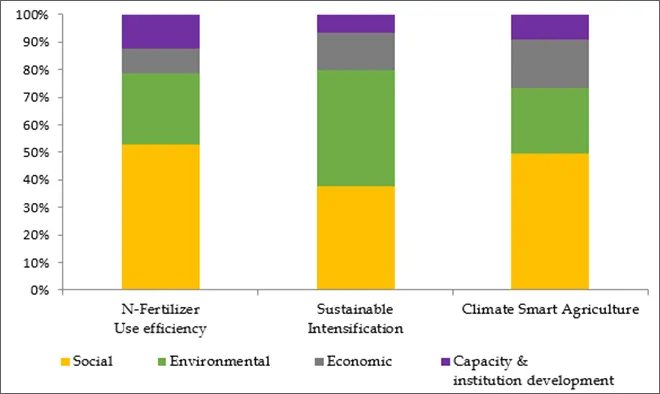

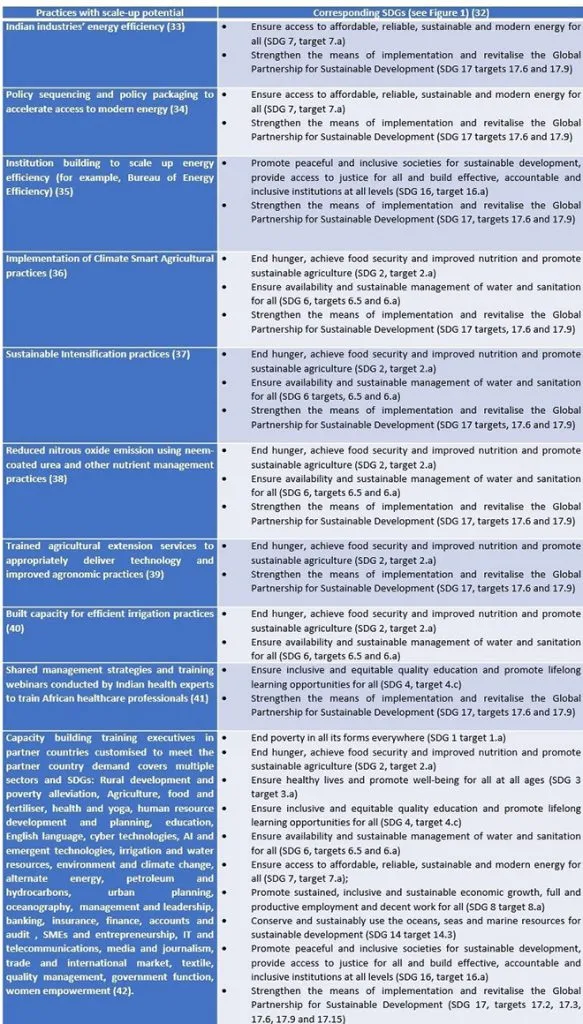

India has taken several actions that are replicable in the developing world (see Table 1) and fit well in its soft power and development diplomacy thrust and the SDG framework.

Table 1: Indian Policy Actions that Can be Replicated

The way forward

The developing countries have large informal sectors and a huge burden of poverty, and need accelerated, yet sustainable, development in the current carbon-constrained environment. India’s success in growing at a quick pace while keeping per capita emissions low despite its large population is a potential model for replication for the developing world.

India can share many best practices through its economic and developmental diplomacy within the SDG framework. Its developmental model — a combination of economic actors and institutions, market links, government funding, private investment, foreign direct investment and multilateral funding — is much like the ones followed in many fast-growing South Asian and African countries (and differ vastly from the ones followed by the OECD, China, South Korea and Singapore<43>)), making its experiences more valuable. India must share technical know-how and societal practices (vegetarianism, using public transport) that has enabled it to remain a low-carbon country (on a per capita carbon accounting basis)<44>.

India can share many best practices through its economic and developmental diplomacy within the SDG framework.

India’s learnings from its experiences with innovation, technology, policy and institutional arrangements should be disseminated widely, enabling the country to provide leadership in development practices across South Asia and Africa. Post-pandemic, India must leverage its experiences with achieving growth while keeping emissions low in diplomatic efforts to show the developing world, and indeed all other countries, the way forward while keeping SDGs at the heart of recovery.

Endnotes

<1> B. Hayward and J. Roy, “Sustainable Living: Bridging the North-South Divide in Lifestyles and Consumption Debates,” Annual Review of Environment and Resource, 44 (2019): 157-175.

<2> United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Paris Agreement, United Nations, 2015.

<3> United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, United Nations, 2015.

<4> J. Roy, S. T. Islam and I. Pal, “Energy, Disaster, Climate Change: Sustainability and Just Transitions in Bangladesh,” International Energy Journal Special Issue 3A (2020): 373-380; United Nations, Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, United Nations (2016).

<5> Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, IPCC, 2018.

<6> David Laborde et al., “COVID-19 Risks to Global Food Security,” Science 369, 6503; Andy Sunmer, Chris Hoy and Eduardo Ortiz-Juarez, “Estimates Of The Impact Of Covid-19 On Global Poverty,” WIDER Working Paper 2020/43, Helsinki, UNU-WIDER, 2020; J. Sachs et al., The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19, Sustainable Development Report (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

<7> Janet Fleetwood, "Social Justice, Food Loss, and the Sustainable Development Goals in the Era of COVID-19," Sustainability, 12 (12) (2020): 5027, 10.3390/su12125027; G. Reddick et al., "Determinants of broadband access and affordability: An analysis of a community survey on the digital divide," Cities, 106 (2020): 102904, 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102904.

<8> Ashri Anurudran et al., "Domestic violence amid COVID‐19," Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2020: 10.1002/ijgo.13247.

<9> Justin Stoler, Wendy E Jepson and Amber Wutich, "Beyond handwashing: Water insecurity undermines COVID-19 response in developing areas," Journal of Global Health, 10(1) (2020): 010355, 10.7189/jogh.10.010355.

<10> B. Barbier, Edward and Joanne C. Burgess, "Sustainability and development after COVID-19," World Development, 135 (2020): 105082, 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020; Hakovirta, Marko, and Navodya Denuwara, "How COVID-19 Redefines the Concept of Sustainability," Sustainability, 12(9) (2020): 3727, 10.3390/su12093727.

<11> Marina Andrijevic et al.,“Governance in Socioeconomic Pathways and iIs Role for Future Adaptive Capacity,” Nature Sustainability 3 (2020): 35-41.

<12> Cameron Hepburn et al. “Will COVID 19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36, Issue Supplement 1 (2020); Gustav Engström et al., "What Policies Address Both the Coronavirus Crisis and the Climate Crisis?" Environmental and Resource Economics volume, 76 (2020): 789-810, 10.1007/s10640-020-00451-y; Paul Malliet et al. "Assessing Short-Term and Long-Term Economic and Environmental Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis in France," Environmental and Resource Economics volume, 76 (2020): 867-883, 10.1007/s10640-020-00488-z.; Erik Gawel and Paul Lehmann, "Killing Two Birds with One Stone? Green Dead Ends and Ways Out of the COVID-19 Crisis," Environ Resour Econ (Dordr), 2020: 10.1007/s10640-020-00443-y.; Vivid Economics, Greenness of stimulus Index— An assessment of COVID-19 stimulus by G20 countries in relation to climate action and biodiversity goals, Vivid Economics, 2020; Climate Action Tracker, Briefing Global Update Pari 5 Years, Climate Action Tracker, 2020.

<13> Soumya Bhowmick, “The Role of SDGs in Post-Pandemic Economic Recovery,” ORF Issue Brief, issue no. 432, 2021.

<14> Joseph S. Nye, “Soft power,” Foreign Policy 80, 153-171.

<15> B. Hayward and J. Roy, “Sustainable Living: Bridging the North-South Divide in Lifestyles and Consumption Debates,” Annual Review of Environment and Resource 44, 2019, 157-175; Narasimha D. Rao, Jihoon Min and Alessio Mastrucci, “Energy requirements for decent living in India, Brazil and South Africa,” Nature Energy 4, 2019, 1025-1032; Narasimha D. Rao and Shonali Pachauri, “Energy access and living standards: some observations on recent trends,” Environmental Research Letters 12 (2), 2017, 10.1088/1748-9326/aa5b0d.

<16> Surjit S. Bhalla, Arvind Virmani and Karan Bhasin, “Poverty, Inequality and Inclusive Growth in India: 2011/12-2017/18,” National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER), 2020.

<17> Jane Golley and Xin Meng, “Income inequality and carbon dioxide emissions: The case of Chinese urban households,” Energy Economics 34 (6) (2012): 1864-1872; Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty, “Carbon and inequality: from Kyoto to Paris: Trends in the global inequality of carbon emissions (1998-2013) & prospects for an equitable adaptation fund,” 2015; Andrew K. Jorgenson et al., “Social science perspectives on drivers of and responses to global climate change,” WIREs Climate Change (2019), 10.1002/wcc.554.

<18> Juliet B. Schor, “Sustainable Consumption and Worktime Reduction,” Journal of Industrial Ecology 9 (1-2): 37-50.

<19> J. Roy et al., “Demand side climate change mitigation actions and SDGs: literature review with systematic evidence search,” Environmental Research Letters, 2021.

<20> L. Hooge and G. Marks, “Multi-Level Governance in the European Union,” in The European Union: Readings on the Theory and Practice of European Integration, 2003; J. Corfee-Morlot et al. “Cities, Climate Change and Multilevel Governance,” OECD Working paper 14, 2009.

<21> J. Roy et al., “Governing National Actions for Global Climate Stabilisation : Examples from India,” in Climate Governance in South Asia, Vishal Narain, Sumit Vij and Barua Anamika (CRC Press-Taylor and Francis Group, 2017).

<22> CII Blog, “India and Africa: Partners in Development,” CII, 18 September 2020.

<23> Roy et al., “Gover ning National Actions for Global Climate Stabilisation”

<24> Zhao, Wenwu et al., "A systematic approach is needed to contain COVID-19 globally," Science Bulletin 65(11) (2020): 876-878, 10.1016/j.scib.2020.03.024.

<25> A. Sen, “Trade policy scenario in post Covid-19 era,” Ernst & Young, 2 May 2020; UNCTAD, COVID-19 and beyond: What role for LDCs? UNCTAD, 12 November 2020; UNESCAP, Promoting inward and outward foreign direct investment in the post-coronavirus-disease era, UNESCAP, January 2021.

<26> United Nations Department of Global Communications, Sustainable Development Goals- Guidelines For The Use Of The SDG Logo Including The Colour Wheel, and 17 Icons, United Nations, May 2020.

<27> Shyamasree Dasgupta and Joyashree Roy, "Analysing energy intensity trends and decoupling of growth from energy use in Indian manufacturing industries during 1973–1974 to 2011–2012," Energy Efficiency (2017): 925-943.

<28> Nandini Das and Joyashree Roy, "India can increase its mitigation ambition: An analysis based on historical evidence of decoupling between emission and economic growth," Energy for Sustainable Development, vol. 57 (August 2020): 189-199.

<29> Das and Roy, “India can increase its mitigation ambition”

<30> S. Some, “Exploring mitigation interventions and SDGs link: Evidences from Indian agriculture,” in Paradigms, Models, Scenarios and Practices for Strong Sustainability, eds Arnaud Diemer et al., 2020.

<31> S. Some, “Economics of Greenhouse Gas Emission Mitigation: A Study of the Indian Agricultural Sector” (Upublished PhD Thesis, Department of Economics, Jadavpur University, 2020).

<32> UN Stats, Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, United Nations, 2020.

<33> Dasgupta and Roy, "Analysing energy intensity trends and decoupling of growth from energy use in Indian manufacturing industries during 1973–1974 to 2011–2012"; Das and Roy 2020, “India can increase its mitigation ambition”

<34> Praveen Kumar, R. Kaushalendra Rao and N. Hemalatha Reddy, “Sustained uptake of LPG as cleaner cooking fuel in rural India: Role of affordability, accessibility, and awareness,” World Development Perspective 4 (2016): 33-37; Ashwini Dabadge, Ashok Sreenivas and Ann Josey, “What Has the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana Achieved So Far?” Economic & Political Weekly 53, 20 (2018).

<35> Dasgupta and Roy, "Analysing energy intensity trends and decoupling of growth from energy use in Indian manufacturing industries during 1973–1974 to 2011–2012"

<36> NICRA, “National Innovations on Climate Resilient Agriculture,” NICRA, 6 January 2020; Some, “Exploring mitigation interventions and SDGs link”

<37> Some, “Exploring mitigation interventions and SDGs link”

<38> Some, “Exploring mitigation interventions and SDGs link”

<39> Some, “Economics of Greenhouse Gas Emission Mitigation”

<40> INDC, Intended Nationally Determined Contribution, Government of India (2015).

<41> “India and Africa: Partners in Development”

<42> Ministry of External Affairs, Indian technical and Economic Cooperation Programme, Government of India, 10 January 2021.

<43> Roy et al., “Energy, Disaster, Climate Change”

<44> World Bank, CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita), The World Bank Group, 10 January 2021.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication —

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication —  Source: Authors’ own

Source: Authors’ own Source: Adapted from Nandini Das and Joyashree Roy

Source: Adapted from Nandini Das and Joyashree Roy  Source: Adapted from Shreya Some

Source: Adapted from Shreya Some

PREV

PREV