To understand India-China relations during the first term of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it is important to place the bilateral within the larger rubric of rapidly changing political forces at work in Asia. For the past two decades, the so-called “Asian Century” has been defined by the rise of China, and to a lesser extent, India’s economic growth. It was also characterised by cooperation between the two Asian giants in a number of forums, such as the BRICS, and even more recently at the New Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). And even though the border remained a point of friction, China and India were often found defending similar positions in global arenas on issues such as trade and climate change.

Figure 2: AIIB Loans (in USD Millions)

Source: AIIB.

Source: AIIB.

This quasi-camaraderie ended in 2012, when President Xi Jinping proclaimed that the Middle Kingdom was committed to realising the “China Dream”<1> by mid-century. Since then, Beijing has attempted to globalise its own “internal arrangement” for organising societies based on a mix of political authoritarianism and state-led capitalism. In 2017, President Xi called this “Socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new Era”<2> and offered it to the world to embrace.

These developments marked an important point of departure for Asia and India. Beijing was now visibly willing to dictate the political, economic and security architecture of the continent—and it had little respect for existing sub-regional groups and balance of power arrangements such as those in South Asia and South East Asia, and extending right up to the European Union. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which seeks to alter extant political geographies and economic models, is China’s most potent tool in this regard.

This expansive geopolitical ambition has naturally given rise to opposition from others. India, as a self-described “leading power,”<3> was the first to vocalise discontent with the BRI—and set the template for the other critics that have emerged since.<4> From this global pushback against China’s geopolitical ambitions emerged a new conceptualisation for Asia: “the Indo-Pacific.” While it was an American construct, India is undoubtedly the lynchpin of this new geography. The framing of this political geography is different from the imagination of the Asian century; this construct is driven not by cooperation, but by contest, conflict and competition.

The past five years of the India-China bilateral have been defined by this one trend: of vacillation between camaraderie in and of the Asian century, to the contest and acrimony in the Indo-Pacific. Consider, for example, the political dynamics of the China-led AIIB. India is the second largest shareholder in this institution that was widely recognised as a juxtaposition between Asia’s rise and America’s diminished influence over the international economic order.<5>

It was also perhaps the strongest indicator of cooperation between India and China. Contrast this with the BRI. China is coopting states in the Indo-Pacific into its broader BRI network to serve its export and national security interests while disregarding the territorial integrity of India and ignoring India’s priorities and vision for Asia.<6>

Similarly, consider India ascension into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The SCO has developed norms that serve as a direct counterpoint to the extant liberal international order. It is an impressive testament to how multipolarity has given rise to new engagements and propositions. From cyberspace to multilateral trade, the Beijing-led organisation is developing uniquely Asian solutions to political, economic and security imperatives. In 2019, in fact, India joined other members to criticise the US’ aggressive attitude to trade.<7> On the other hand, India is also invested in a revival of the Quadrilateral initiative. A grouping of democracies in the Indo-Pacific, the Quad seeks to preserve a democratic and rules-based order in the region. Like the SCO, the Quad’s cooperation is multifaceted and encompasses infrastructure investment, cyber norms and maritime security cooperation. Only this time, it is China’s mercantilist trade and investment propositions and its maritime coercion that India seeks to respond to.

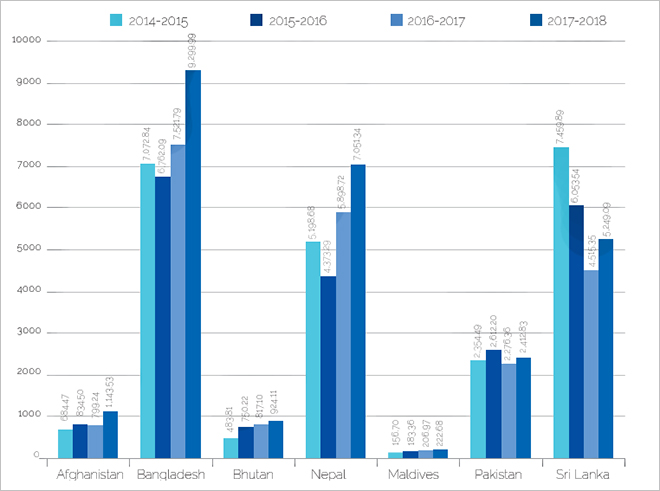

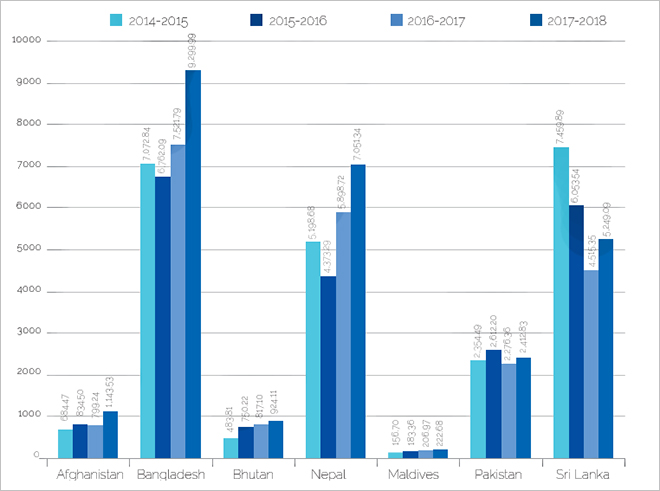

Figure 3: India-China Trade

Source: WTO

Source: WTO

Clearly there are two contradictory forces that drive the bilateral today: the appeal of an Asian Century that seeks to escape the burdens of colonialism, and a contest in the Indo-Pacific to avoid a new form of subjugation. This dynamic was invariably going to produce new friction and ultimately culminated in a skirmish in the Himalayas. The Doklam Standoff in the summer of 2017 marked the nadir in India-China relations and the sharpest decline in bilateral relations between the two powers in over four decades. Fundamentally, the dispute was a struggle to define and then manage Asia.<8> The stand-off will likely be remembered as a moment when ‘a’ sovereign finally stood up to China’s aggressive attempts to redraw political maps. Beijing is unlikely to either forget or forgive this. It will be naïve to ignore the acrimony, unease, contest and struggle that has defined the relationship between the two countries ever since.

Politically, China has attempted to choke India’s options. Beijing is not being petty when it refuses to allow Masood Azhar’s listing as a global terrorist, or when it objects to the Dalai Lama’s travels in India or refuses to accept India into the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). With these actions, China is being unrelentingly strategic in undermining India’s capacity to influence global and regional political developments.

On the economic and trade front, the numbers tell an obvious story about how China views the relationship with India: as a mere market for its manufactured industrial and consumer goods. China’s mercantilism offers no room for partnership; only dependence. Despite multiple negotiations in which India has indicated its displeasure with the negative balance of trade, the difference has only gotten larger.

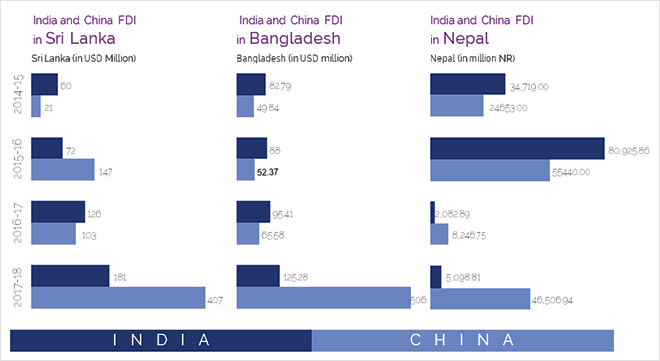

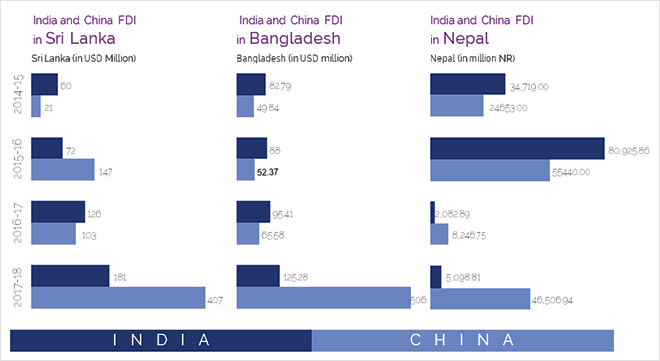

On the security front, Beijing has been completely disregarding India’s sovereign concerns in Kashmir by investing in the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. It has also attempted to undermine India’s economic influence around the neighbourhood, most dramatically in the Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka even as it sustains its overtures to Bangladesh (See Figure 4).<9> The Middle Kingdom has also been unrelenting with its pressure around Doklam, with satellite imagery suggesting that it maintains a growing security presence in the region.<10>

By exercising diplomatic, economic and military pressure on India within the sub-region, China is positioning itself to unilaterally design the continent’s

Figure 4: India FDI v. China FDI

Sources: Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh Bank, and Nepal Rastra Bank

Sources: Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh Bank, and Nepal Rastra Bank

security and political architecture. This vision is at odds with the original conceptualisation of the “Asian Century,” which was fundamentally a story of the rise of a group of countries in the region. Indeed, 21st-century Asia will not be defined by a solidarity of developing countries led by China and India. Instead, it will be defined by Beijing’s attempt to integrate, on its own terms and for its own interests, the Eurasian landmass.

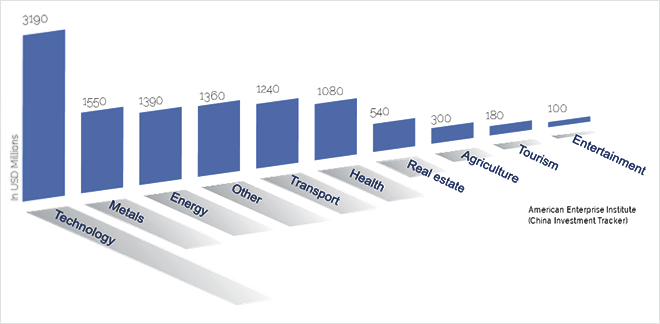

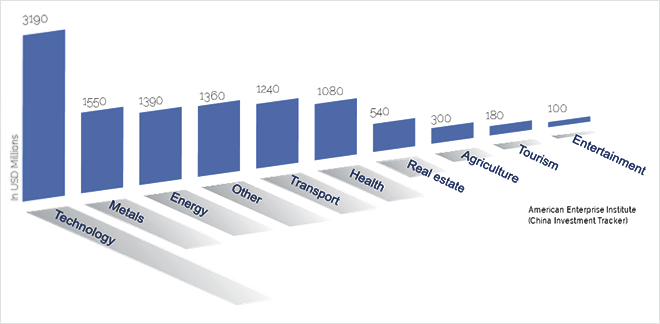

Before India can respond to China with its own propositions, it must acknowledge another set of contradictory forces that drive the relationship: even while China may apply tremendous pressure on the political and security front, it has also emerged as the largest investor in key areas that are likely to drive India’s economic growth (See Figure 5). As India’s economy moves towards the US$5-trillion mark, both political friction and economic engagement will only increase. In managing this, India will find little help from the North-Atlantic countries—who are themselves struggling to set the terms of engagement with China, both individually and collectively. Italy’s decision to join the BRI and the EU’s inability to decide on the future of 5G infrastructure only drive home the point.<41>

India will have to build its own capacity to resist and counteract China’s political aggression, even as it embraces investments and commercial opportunities. This is certainly easier said than done. However, China in its own emergence has demonstrated the method to do this. For years, it benefited from the American economy and investments even as it pushed back against a US-led world order and its presence in the Western Pacific. This is a template that India must emulate.

Figure 5: Chinese Investments in India (in USD Millions)

Source: China Investment Tracker, American Enterprise Institute.

Source: China Investment Tracker, American Enterprise Institute.

This will be the government’s most complex task: navigating the disconnect between the opportunities of the Asian Century and the hard realities of the Indo-Pacific. Even as India leverages Chinese investments to fuel its growth, it must offer to Asia and the world an alternative model for development that is based on democracy and a proposition for security based on international rules and institutions. Which conceptualisation eventually characterises Asia will invariably define the contours of the world in the 21st century.

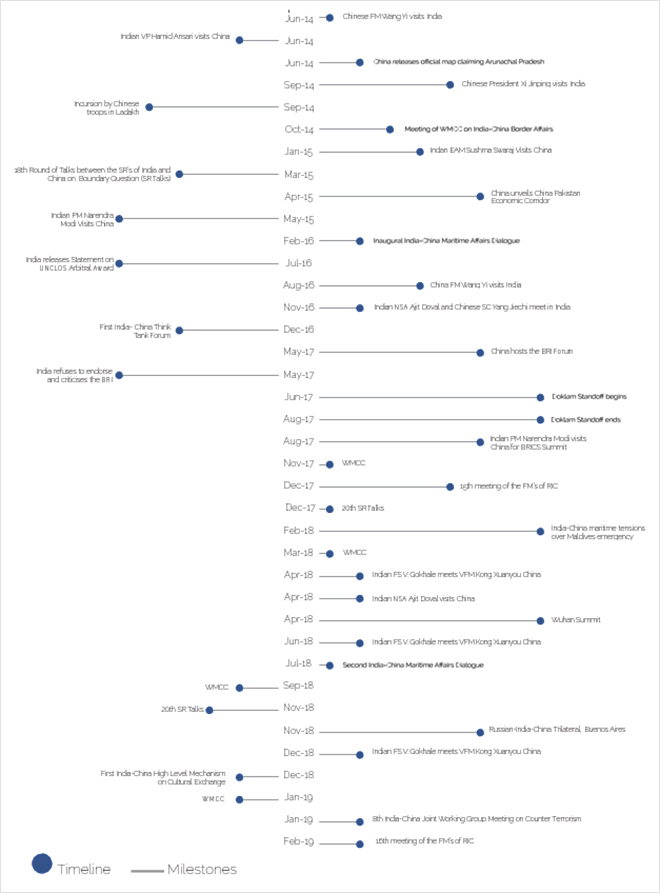

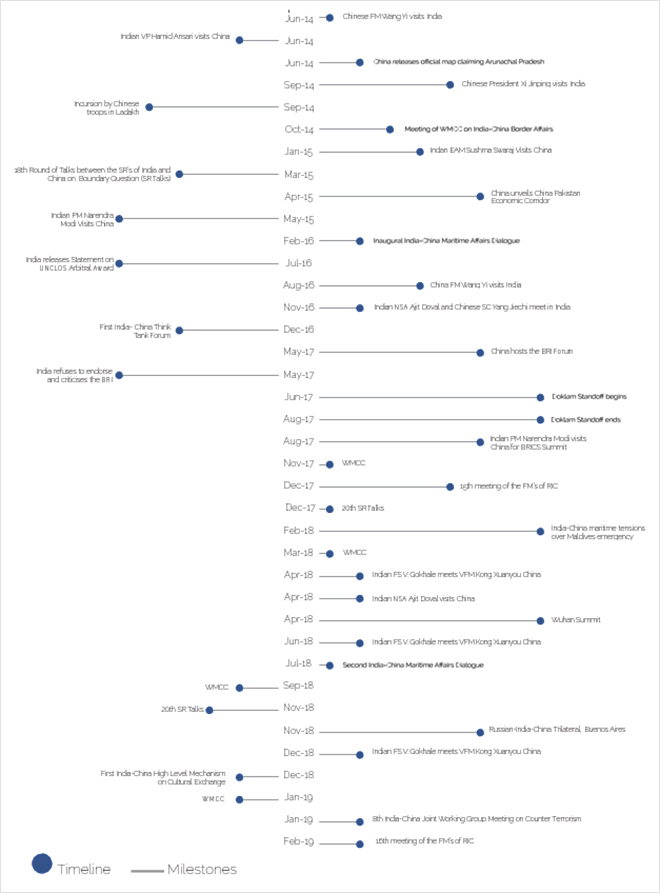

Figure 6: A Timeline of India-China Engagement (2014-’19)

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, India

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, India

This article originally appeared in special report Looking Back looking Ahead.

End Notes

<1> “Chinese Dream,” China Daily.

<2> Xiang Bo, “Backgrounder: Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” Xinhuanet, 17 March 2018.

<3> “IISS Fullerton Lecture by Dr. S. Jaishankar, Foreign Secretary in Singapore,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 20 July 2015.

<4> “Official Spokesperson’s Response to a Query on Participation of India in OBOR/BRI Forum,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 13 March 2017.

<5> ANI, “India Is Second Largest Shareholder Of AIIB: Piyush Goyal,” Business- Standard, 24 June 2018.

<6> Samir Saran and Sushant Sareen, “Battle for South Asia 2.0,” ORF, 27 September 2018.

<7> Dipanjan Chaudhury, “India Likely to Join China-Russia Call for New Trading System on SCO Sidelines,” The Economic Times, 10 June 2019.

<8> Samir Saran, “India Sees the Belt and Road Initiative for What It Is: Evidence of China’s Unconcealed Ambition for Hegemony,” ORF, 19 February 2018.

<9> Ashlyn Anderson and Alyssa Ayres, “Economics of Influence: China and India In South Asia,” Council on Foreign Relations, 3 August 2015.

<10> Vinayak Bhat, “Near Doklam, China Is Again Increasing Forces, Building Roads & Even A Possible Heliport,” The Print, 2 April 2019.

<11> Colin Lecher, “Europe Is Worried About 5G Security, But It Isn’t Banning Huawei Yet,” The Verge, 26 March 2019.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: AIIB.

Source: AIIB. Source: WTO

Source: WTO Sources: Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh Bank, and Nepal Rastra Bank

Sources: Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh Bank, and Nepal Rastra Bank Source: China Investment Tracker, American Enterprise Institute.

Source: China Investment Tracker, American Enterprise Institute. Source: Ministry of External Affairs, India

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, India PREV

PREV