This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

India has a long history of partnership with Africa, with solidarity and political affinity going back to the early 1920s when both regions were fighting against colonial rule and oppression. India’s freedom movement had an internationalist outlook; many Indian nationalists viewed the struggle for independence as part of the worldwide movement against imperialism. After India gained independence, it became a leading voice in support of African decolonisation at the United Nations. Independent India, though extremely poor after two centuries of colonial exploitation, strived to share its limited resources with African countries under the banner of South-South cooperation. In 1964, India launched the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) programme to provide technical assistance through human resource development to other developing countries, with African countries the greatest beneficiaries of it and the Special Commonwealth African Assistance Programme (SCAAP).

India’s total trade with Africa grew from US$ 6.8 billion in 2003 to US$ 76.9 billion in 2018, and India is now Africa’s third-largest trade partner.

India’s economic engagement with Africa, on the other hand, only began intensifying in the early 2000s. India’s total trade with Africa grew from US$ 6.8 billion in 2003 to US$ 76.9 billion in 2018, and India is now Africa’s third-largest trade partner<1>. Indian investments in Africa have also grown rapidly in the last decade and the country is currently the seventh-largest investor in Africa<2>. The scale of India’s development cooperation with Africa has also grown rapidly. From 2003 onwards, India began to use concessional lines of credit (LoC) as one of its key development partnership instruments to fund the construction of railway lines, electrification and irrigation projects, farm mechanisation projects, among others. The LoCs are demand-driven and extended on the principle of mutual benefit — recipient countries make development gains, while the LoCs help create new markets for Indian companies, foster export growth, build good relations with countries that are important sources of food, energy and resources, and contribute to the country’s image abroad. So far, India has sanctioned 182 LoC projects in Africa through the Export Import (EXIM) Bank of India, with a total credit commitment of about US$ 10.5 billion<3>. Indian LoCs have significant development impacts in Africa. For instance, India’s irrigation project in Senegal led to a six-fold increase in rice production and currently over 30 percent of that country’s consumption is covered by domestic production, as compared to 12.1 percent prior to the implementation<4><5>. Similarly India’s LoC worth US$ 640 million to Ethiopia helped the country become self-sufficient in sugar production and had major spill-over benefits<6>. The sugar factory installed a water-purification plant, which benefited nearly 10,000 villagers who previously relied on untreated water, and pastoralists in the region now have access to a stable source of income<7>.

Building African capacity

Although India was poor and underdeveloped after two centuries of colonial exploitation, it launched systematic efforts to promote African development soon after its independence. In 1949, India announced 70 scholarships for students from other developing countries to pursue studies in the country<8>. The ITEC programme, launched to share India’s lessons in development with other developing countries, continues to remain an important pillar of Indian development cooperation programme. Currently, about 98 Indian institutions run training courses in fields such as agriculture, food and fertiliser, engineering and technology, and environment and climate change<9>. In addition to civilian training programmes, ITEC also conducts and oversees defence training programmes, study tours, aid for disaster relief, the deputation of Indian experts abroad and project-based cooperation. Africa is a key beneficiary of the programme with nearly 50 percent of the ITEC slots reserved for countries from the region.

The ITEC programme, launched to share India’s lessons in development with other developing countries, continues to remain an important pillar of Indian development cooperation programme.

India-Africa cooperation has also focused on technoeconomic capacity building. Skill development and capacity building featured prominently in all the India-Africa Forum Summits, and in a speech to the Ugandan parliament in 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi reiterated India’s commitment to building African capacity: “Our development partnership will be guided by your priorities. It will be on terms that will be comfortable for you, that will liberate your potential and not constrain your future. We will rely on African talent and skills. We will build as much local capacity and create as many local opportunities as possible<10>.”

Information technology (IT) is an important pillar of India’s technical cooperation with Africa, given the role of the information and communication technology (ICT) sector in India’s growth story and the importance most African leaders attach to ICT sector development. The Pan African e-Network, launched in 2009, was a groundbreaking initiative to extend Indian expertise in IT to provide better healthcare and education facilities in 53 African countries. The second phase of this programme, e-VidyaBharti and e-ArogyaBharti (e-VBAB), was started in 2018, with an aim to provide free tele-education to 4,000 African students each year for five years and continuing medical education for 1000 African doctors, paramedical staff, and nurses<11>. The programme is fully funded by the Indian government and is web-based, so any Indian university qualified to offer online education can do so for African students.

India’s scholarship programme also grew rapidly. At the third India-Africa Forum Summit in 2015, India pledged to provide 50,000 scholarships to African students over a five-year period and set up institutions of higher learning in Africa. Over 42,000 scholarship slots have already been utilised in the last five years.

At the third India-Africa Forum Summit in 2015, India pledged to provide 50,000 scholarships to African students over a five-year period and set up institutions of higher learning in Africa.

In 2018, India’s Ministry of Human Resource and Development launched the ‘Study in India’ initiative to attract students from neighbouring and African countries. Foreign students can choose from 1,500 courses being offered at the undergraduate, graduate and PhD level by public and private institutions in India, and meritorious students could receive up to 100 percent fee waivers. However, the initiative has not been successful in attracting African students to India. Most foreign students who come to India only opt for the Indian Institutes of Technology through academic collaborations (and not the ‘Study in India’ programme)<12>. Of the top ten countries with the most number of students in India (making up about 63.9 percent of all foreign students in the country), only two are African — Sudan, accounting for 4.5 percent of foreign students, and Nigeria, with a 3.4 percent share (see Table 1)<13>. Foreign student enrolment for higher education programmes such as PhDs is also far lower than undergraduate programmes, highlighting that India is not perceived as an appropriate destination for higher education and research<14>.

Table 1: Country-wise distribution of foreign students in India (Top 10)

| Country |

No. of Students |

Share (%) |

| Nepal |

12,747 |

26.8 |

| Afghanistan |

4,657 |

9.8 |

| Bangladesh |

2,075 |

4.4 |

| Sudan |

1,905 |

4 |

| Bhutan |

1,811 |

3.8 |

| Nigeria |

1,614 |

3.4 |

| United States |

1,518 |

3.2 |

| Yemen |

1,498 |

3.2 |

| Sri Lanka |

1,252 |

2.6 |

| Iran |

1,127 |

2.4 |

| Total |

47,427 |

|

Source: Ministry of Human Resource Development (2019)<15>

China, on the other hand, has been viewed as a more attractive destination for higher studies to African students. Between 2003 and 2015, the number of African students in China increased from less than 2,000 to about 50,000<16>. China is currently the second most popular destination for African students after France, which hosts about 95,000 African students. The US and the UK, the two most popular destinations for international students, host about 30,000 African students each<17>.

Although the quality of education varies from institution to institution, even India’s most prestigious institutes do not meet global standards on infrastructure, research and faculty-student ratio.

The poor quality of education in India is the primary reason it is not the foreign destination of choice for African students. The Concept Note by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry and the Confederation of Indian Industry presented at the India-Africa Higher Education and Skill Development Summit in September 2019 describes India’s higher education sector as “reputable, older and more developed”<18>. But African students objected about the quality of education in India: “What you hear and read about the quality of Indian education, and what it actually is, are two totally different things. There are some colleges which the Indian government shouldn’t allow them to admit international students in the first place. They simply aren’t good enough. They neither have a good set up, nor well-trained teachers. Just because you have thousands of colleges doesn’t mean every one of them is good. Certain amount of streamlining is required”<19>. Although the quality of education varies from institution to institution, even India’s most prestigious institutes do not meet global standards on infrastructure, research and faculty-student ratio. According to the All Survey on Higher Education 2018-19, India has 993 registered universities<20>, yet not even one features among the world’s top 100, not even most reputable Indian institutions such as the Indian Institutes of Technology.

Cooperation on global issues

India and Africa have often held common positions in global platforms and worked together to guard the interests of other developing countries. They have moved joint proposals, such as the Agricultural Framework Proposal and Protection of Geographical Indications, at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and World Intellectual Property Organisation, and have worked towards protecting the food and livelihood concerns of farmers at the Doha Development Round of WTO negotiations. The ‘Framework for Strategic Cooperation,’ the outcome document of the Third India-Africa Forum Summit, also mentions that India and Africa will “enhance cooperation through training and collective negotiations on global trade issues, including at the WTO to protect and promote the legitimate interests of developing countries, especially the LDCs ”<21>. India and South Africa are also currently pressing for a waiver of certain provisions of the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights for COVID-19 treatment and vaccines<22>.

Nearly half of all member countries in the International Solar Alliance, initiated by India, are from Africa.

India and Africa have also coordinated responses in climate action negotiations. Nearly half of all member countries in the International Solar Alliance, initiated by India, are from Africa. India has announced an LoC worth US$ 2 billion to Africa over five years for the implementation of off-grid solar energy projects and is working to develop solar power systems across the Sahel region to provide electricity to approximately half of the 600 million Africans who are currently off-grid<23>.

India has also aided African countries amid crises, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. India has provided 270 metric tonnes of food aid (155 metric tonnes of wheat flour, 65 metric tonnes of rice, and 50 metric tonnes of sugar) to Sudan, South Sudan, Djibouti and Eritrea<24>, and supplied essential medicines (including hydroxychloroquine and paracetamol) to over 25 African countries<25>. The Indian government also organised an e-ITEC training course for healthcare professionals on COVID-19 prevention and management protocols<26>. And even as developed countries have focussed on securing large vaccine supplies for their own populations, India is being hailed for its vaccine diplomacy — it has exported over 1.6 crore doses of vaccines globally, of which about 62.7 lakh doses (or about 37 percent) are as grant assistance<27>. Mauritius and Seychelles have received 1 lakh doses and 50,000 doses, respectively, via the grant route.

Limitations to India’s approach

Despite being a developing country with huge domestic challenges, India has played an important role in building African capacity, with several notable ongoing initiatives. Additionally, the values that steer India’s development cooperation — demand driven, conditionality free and based on the principle of partnership among equals — are appreciated in Africa. But India’s model of development cooperation in Africa lacks a clear strategy. Beyond the ‘platitudes that they do business differently,’ it has so far proved tricky to distinguish what shape the ‘Indian model’ of cooperation with Africa would assume in practice. While it is increasingly obvious that the postcolonial rhetoric inherited from the Nehru years has limited relevance in the current global economic context, it remains difficult to pinpoint India’s position in contrast with other major players”<28>. In the absence of a clear and well-articulated vision for Africa, India’s development cooperation is often compared to the Chinese model of development cooperation in the region<29> — despite significant differences — which is based on state-led infrastructure for resources deals, rising debt threats, lack of domestic capacity building and job creation. In 2018, Modi outlined the ‘Ten Guiding Principles for India-Africa Engagement’<30>, often regarded as India’s vision statement for Africa. But these tenets cannot be seen as the mission for the next decade because many aspects are not new and instead represent continuity in principles that have traditionally defined India-Africa engagement<31>.

Beyond the ‘platitudes that they do business differently,’ it has so far proved tricky to distinguish what shape the ‘Indian model’ of cooperation with Africa would assume in practice.

There are two main flaws in India’s development strategy in Africa. Firstly, India is not actively pursuing any specific development goals. An assessment of India’s development cooperation instruments (LoCs, grants, and capacity building projects like ITEC) reflects the absence of a plan for Africa. Indian LoCs have not been designed to achieve a larger development goal such as food security, health security, clean energy or education for all. LoCs are typically used by recipient countries to fund small development projects such as roads, bridges, railway lines, power transmission and water supply systems. Although the individual projects have development benefits for recipient countries, the overall development impact of Indian LoCs in Africa is not significant. These individual projects barely make a dent on any of the larger development challenges (for instance, food insecurity, health insecurity, poverty) in African countries.

Secondly, there is no synchronisation between different development instruments. LoCs, grants and capacity building initiatives operate as standalone instruments of development cooperation, with almost no links with each other. As a result, the overall development impact of India’s development cooperation is small and difficult to measure. “India-Africa partnership is yet to achieve its full potential. What is needed is an infusion of energy, of something new and concrete, and with a specific focus and direction”<32>. Moreover, implementation has been a key constraint for Indian LoCs, with poor disbursal rates and project completion record.

India must chart out a roadmap for its development cooperation programme in Africa that outlines a long-term strategy and delineates how it will deploy state capacity to pursue common development goals. Doing so will become even more important for India in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic given the harsh economic impacts and the resultant inability to keep increasing its development cooperation budget without any tangible outcomes.

There have been numerous cases of violence against African students in India.

Although India projects its engagement with Africa as an ideal model for cooperation within the Global South, with frequent references to India’s support of African decolonisation and Afro-Asian solidarity, instances of violence against African students is common in India. There have been numerous cases of violence against African students in India and most African students complain of harassment and discrimination, with many leaving India without finishing their studies<33>.

COVID-19 setback and the way forward

India is among the African continent’s oldest and most consistent development partners, and the country has gained tremendous goodwill in the region. Unlike many Western countries that carry the baggage of colonialism or China, which has been severely criticised for its debt-trap diplomacy, disregard for local laws and lack of local employment creation in Africa, India enjoys good ties with the African states.

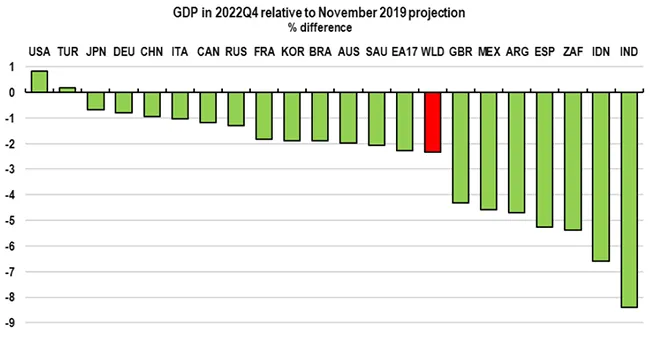

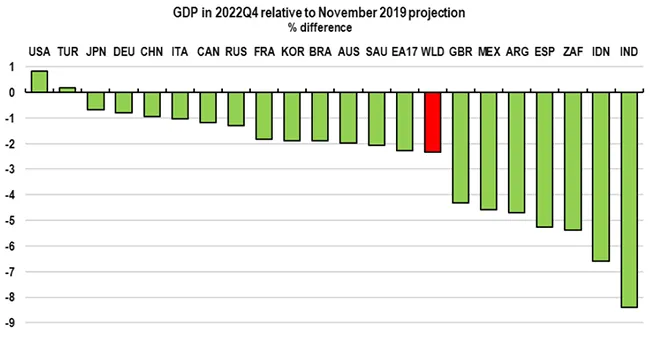

The coming decade presents massive development challenges for India and Africa, which have both been severely affected by the socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. India’s GDP declined by 8 percent in 2020<34> and about 10.9 million jobs were lost across the country<35>. Poverty and hunger are also on the rise<36>. A strong recovery in 2021 is unlikely to reverse the damage caused by the lockdown. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development forecasts suggest that India’s real GDP in the fourth quarter of 2022 will be over 8 percent lower than its pre-pandemic prediction (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Risk of Lasting Cost From the Pandemic Remains High In Many Countries

Source: OECD (2021)<37>

Source: OECD (2021)<37>

Note: The November 2019 projections are extended to 2022 using the November 2019 estimates of the potential output growth rate for each economy in 2021.

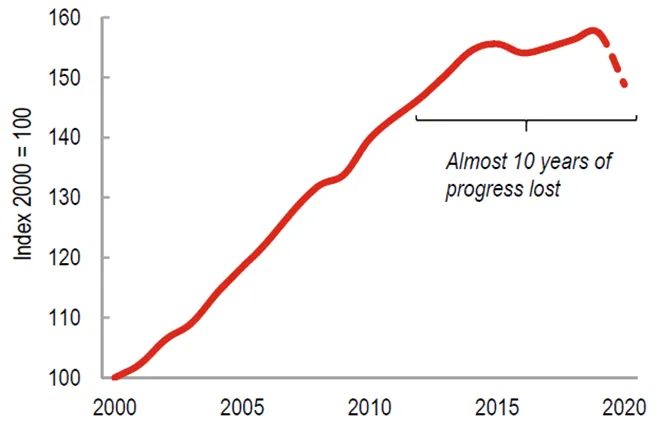

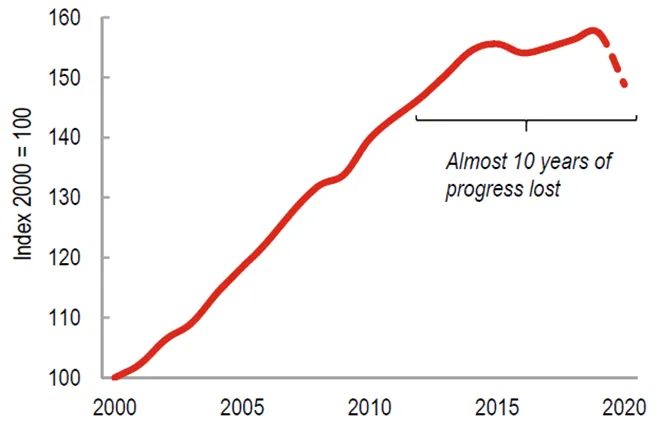

The COVID-19 pandemic is also expected to completely wipe out economic progress made by Sub-Saharan Africa in the previous decade. According to International Monetary Fund (IMF), the real per capita GDP of the region will decline by 5.4 percent in 2020, bringing it back to the 2010 level (see Figure 2). The pandemic is likely to push about 26 million more people into extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa and income inequality is also expected to increase substantially. Most African countries also do not have the fiscal room to fund large stimulus packages to revive their economies. Rising debt levels were already a concern for many African countries, but the pandemic and the associated loss in economic growth has made things worse for the region. Amid the pandemic, the G20 nations announced the Debt Service Suspension Initiative that allowed the world’s poorest countries — most of them in Africa — to suspend up to US$ 14 billion of debt service payment due in 2020. Twenty-nine African countries have also received IMF funding from emergency facilities or programme arrangements. But given the scale of the crisis, these efforts are not enough. The pandemic has widened Africa’s financing gap to US$ 345 billion and it will be extremely difficult for countries in the region to find the resources to meet the Sustainable Development Goals<38>.

The pandemic is likely to push about 26 million more people into extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa and income inequality is also expected to increase substantially.

Figure 2: Sub-Saharan Africa’s real GDP per capita (2000 to 2020)

Source: IMF (2020)<39>

Source: IMF (2020)<39>

Hard won development gains have been lost in India and Africa due to the pandemic. Poverty, unemployment and hunger are on the rise. Given the enormity of the challenges before India and Africa, closer cooperation is essential. However, domestic needs will not allow India to substantially increase its development aid budget. With its limited resources, India can try to make its development cooperation with Africa more impactful in the following ways:

• Clear strategy for African development: Both India and Africa face major challenges in the next decade. Unlike China and the West, India does not have substantial resources to support Africa. Therefore, it should prepare a focused Africa strategy for the next decade and identify a few areas for closer cooperation. Targeting a few important areas like food and health security, climate change adaptation and gender equality will help improve development outcomes and make India's development cooperation programme more effective.

• Continue the current focus on capacity building: Commodity-led high growth in the last decade did not lead to adequate job creation and poverty alleviation in Africa. Therefore, a simple focus on building physical infrastructure and economic growth will not contribute to a stable and prosperous Africa. Investment in human capital is the key to development in Africa. The current focus on capacity building is in line with Africa’s needs given the continent’s huge youth population that need skills and jobs.

• Harness Indian civil society organisations, NGOs, and Indian diaspora: Many Indian civil society organisations and NGOs are playing an important role at the grassroots. Some Indian organisations like Pratham and Barefoot College are also playing an important role in Africa. The Indian government should explore greater collaboration with these organisations to implement development projects in Africa at low costs. (See Navdeep Suri and Anurag Reddy’s chapter in this series for more details)

• Promote development-friendly private investments: The presence of Indian companies in Africa has grown rapidly in the last two decades. Given the emphasis on mutual benefit in its strategy, India’s development cooperation should be aligned to its commercial interests in Africa. Therefore, India should try to support Indian companies making investment in development-friendly projects for mutual benefit<40>.

• Timely completion of projects: Though some improvement in project implementation has occurred in recent years, India’s overall record is poor. Efforts must be made to expedite the LoC projects. Lessons should be drawn from other countries that have a much better record in implementation.

• Address concerns about academic experience in India: India’s record in providing higher education to African students has been patchy. Although it is too early to judge the ‘Study in India’ programme, initial results do not seem to be promising as very few African students prefer to come to India. Merely extending scholarships to African students will not be enough to increase the flow of African students to the country. Also, affordability is not the only consideration for international students who are looking for a wholesome academic experience, which includes living conditions, quality of education, exposure, the institution’s global ranking and cultural experience. Therefore, India must make largescale investments in its own higher education sector to project itself as an education hub for neighbouring countries and Africa.

• Improve the experiences of Africans in India: The Indian government is usually quick to respond to instances of Indian students facing racism in foreign countries. It should respond to instances of harassment and attacks on African students with the same alacrity. Incidents of race attacks on African nationals have severely dented India’s image. If untreated, this could be a potential source of tension between India and Africa and damage the goodwill India currently enjoys in the continent. Therefore, the Indian government should ensure that Africans studying or working in India are safe and enjoy their stay in the country. Efforts should also be made to educate Indians about Africa so that people-to-people connections between India and Africa flourish.

Endnotes

<1> World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), “UN COMTRADE,” World Bank.

<2> Malancha Chakrabarty, “Indian Investments in Africa: Scale, Trends, and Policy Recommendations,” ORF Occasional Paper 142, February 2018.

<3> India Exim Bank, “Financial Products,” India Exim Bank.

<4> Digital Repository, “A political economy approach of India in Senegal. A “winwin” partnership?” Universitat de Barcelona.

<5> H. H. S. Viswanathan and Abhishek Mishra, “India-Africa partnership for food security: Beyond strategic concerns,” ORF Occasional Paper 242, 24 April 2020.

<6> Asgar Qadri and Rajrishi Sehgal, “Development and Diplomacy through Lines of Credit Achievements and Lessons Learnt,” ORF Occasional Paper 53, 1 September 2014.

<7> Qadri and Sehgal, “Development and Diplomacy through Lines of Credit Achievements and Lessons Learnt”

<8> Sachin Chaturvedi, “The Logic of Sharing: Indian Approach to Development Cooperation,” Research and Information System for Developing Countries, 2014.

<9> Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation Programme, “India’s Development Partnership,” Government of India.

<10> Prime Minister’s Office, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, 25 July 2018.

<11> “Ministry of External Affairs," Government of India, 10 September 2018.

<12> Arnab Mitra, “Two years of ‘Study in India’ later, number of foreign students sees marginal rise,” Indian Express, 26 January 2020.

<13> Ministry of Human Resources and Development, All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19, New Delhi, MHRD, Government of India, 2019.

<14> “All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19”

<15> “All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19”

<16> Victoria Breeze and Nathan Moore, “China tops US and UK as destination for anglophone African students,” The Conversation, 28 June 2017.

<17> Ben Waxman and Liv Radue, “Out of Africa, Part 2: African Students Studying Abroad,” Intead, 10 July 2019.

<18> “India-Africa Higher Education and Skill Development Summit,” Ministry of Commerce and Industry and Confederation of Indian Industry, New Delhi, 26 – 27 August 2019.

<19> Bikash Mohapatra, “‘Study in India’ and India’s African Dilemma,” The Diplomat, 10 June 2019.

<20> All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19

<21> “India-Africa Framework for Strategic Cooperation,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 29 October 2015.

<22> Ann Danaiya Usher, “South Africa and India push for COVID-19 patents ban,” The Lancet, 5 December 2020.

<23> Ministry of External Affairs, “Transcript of Media Briefing on Founding Conference of ISA (March 11, 2018),” Government of India, 12 March 2018.

<24> Kaustuv Chakrabarti, “India’s medical diplomacy during COVID19 through South South Cooperation,” Observer Research Foundation, 9 July 2020.

<25> Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

<26> Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation Programme, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

<27> Chethan Kumar, “Vaccine diplomacy: 37% doses exported are grants,” The Times of India, 16 February 2021.

<28> Vincent Duclos, “Building Capacities: The Resurgence of Indo-African Technoeconomic Cooperation,” India Review, 11:4, 209-225.

<29> Harry G. Broadman, “China and India Go to Africa: New Deals in the Developing World,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 87, no. 2 (March - April 2008), pp. 95-109.

<30> Narendra Modi, “Prime Minister’s address at Parliament of Uganda during his State Visit to Uganda” (speech, Uganda, 25 July 2018), Ministry of External Affairs.

<31> H. H. S. Viswanathan and Abhishek Mishra, “The ten guiding principles for India-Africa engagement: Finding coherence in India’s Africa policy,” ORF Occasional Paper 200, 25 June 2019.

<32> Viswanathan and Mishra, “The ten guiding principles for India-Africa engagement”

<33> Indulekha Arvind, “Africans across India share their experience of living here,” Economic Times, 14 February 2016.

<34> National Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, Government of India.

<35> M Saraswathy, “Covid-19 job impact: Which sectors lost the most people and which ones hired the most in 2020?” MoneyControl, 12 January 2021.

<36> Flore de Preneuf, “Food Security and COVID-19,” The World Bank, 5 February 2021.

<37> OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2021, Paris, OECD Publishing, OECD, 2021.

<38> United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, “About ARFSD 2021,” UNECA.

<39> “Six Charts that Show Sub-Saharan Africa’s Sharpest Economic Contraction Since the 1970s,” IMF News, 29 June 2020.

<40> Malancha Chakrabarty, “Indian Investments in Africa: Scale, Trends, and Policy Recommendations,” ORF Occasional Paper 142, February 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: OECD (2021)

Source: OECD (2021) Source: IMF (2020)

Source: IMF (2020) PREV

PREV