The annual address from the ramparts of the Red Fort is Prime Minister Modi’s prime vehicle for mass outreach, other than via his Twitter handle. His style—discursive, evocative, and expansive—suits the occasion where substance needs to take a back seat to rhetoric.

All these are good reasons for not looking too deeply into the substance of the speech—unlike, for instance, the annual budget speech of the Finance Minister, but that would be throwing out the baby with the bath water. Throughout his term as prime Minister, his Independence Day speeches chart the evolution of his thinking. The speech and the Prime Minister evolved from simple homilies in 2014 to concrete domestic action in 2015

–2017, transitioning over 2018

–2021 to shaping long-term national aspirations till 2047.

Border tensions and skirmishes and tit-for-tat trade retaliatory (collaterally inflation stoking) tariff measures became mechanisms for India’s realignment with the ‘Western Alliance’.

The last three years have been rocky. India-China cooperation lost steam by 2019. The Asian giants drifted apart sensing mutually misaligned objectives and few complementarities. Border tensions and skirmishes and tit-for-tat trade retaliatory (collaterally inflation stoking) tariff measures became mechanisms for India’s realignment with the ‘Western Alliance’. The following years 2020 and 2021 were clouded by the COVID-19 pandemic. The government did well to step up welfare spending despite a ballooning fiscal deficit (9.2 percent of GDP during FY 2021) which continues at high levels of 6.4 percent this fiscal. Nor has the current fiscal year (2022) been propitious. India is highly susceptible to imported inflation—mostly due to fuel (coal, oil, and gas) and edible oil. Not being a net exporter of fuels, it is at the receiving end of the Ukraine crisis-led commodities boom.

Navigating the learning curve

There were early systemic setbacks. The first was the growth-dampening impact of demonetisation, unadvisedly used as a tool to stamp out corruption. To its credit, the government quickly pivoted by adding more effective, systemic measures like incentivising the Aadhaar-linked digitalisation of payments and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) which made tax evasion difficult. Tax revenues have been buoyant, despite lowering corporate tax rates to around 25 percent for existing firms and 15 percent for new firms in 2021.

Real growth levels have been progressively lower since 2017

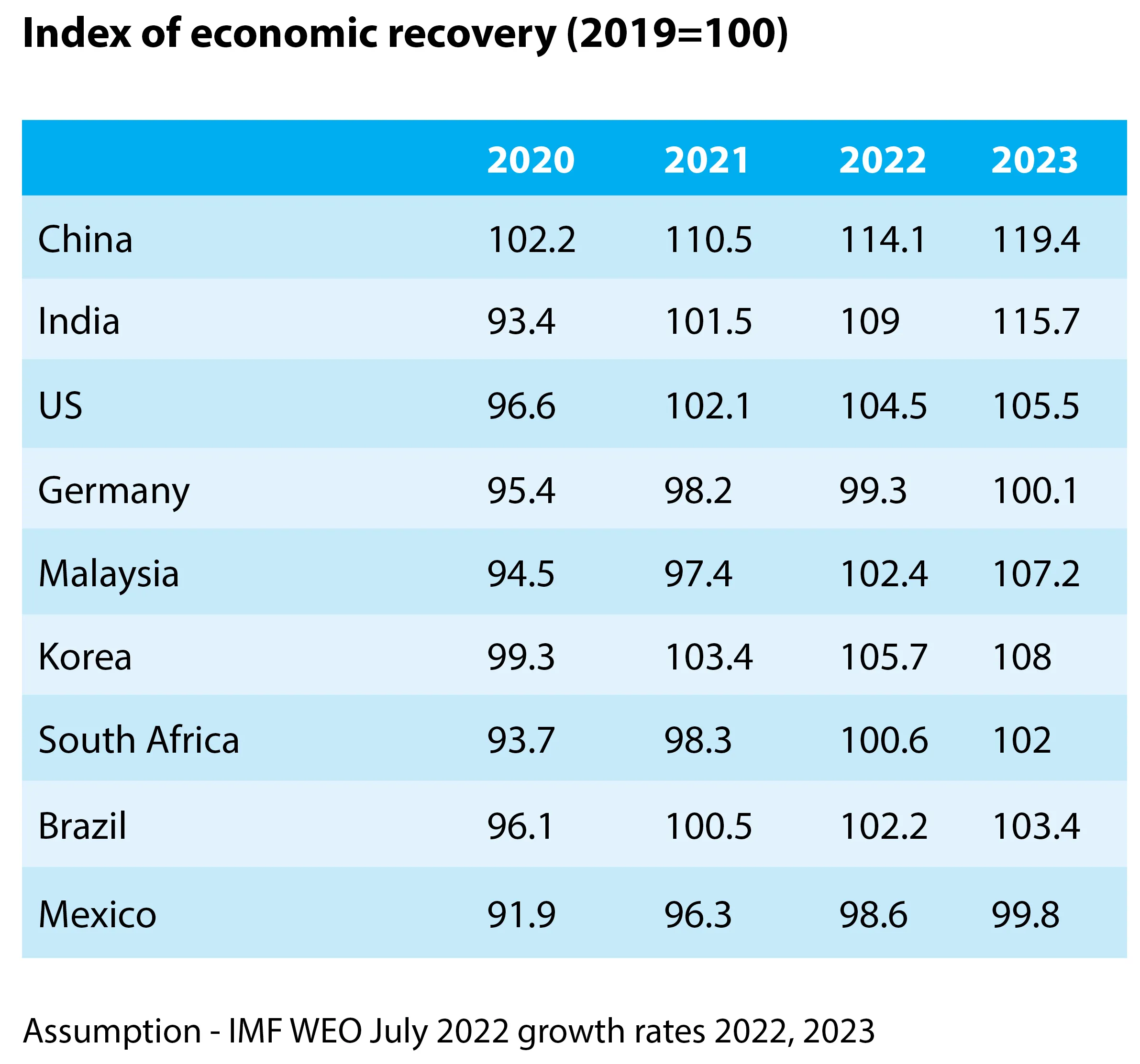

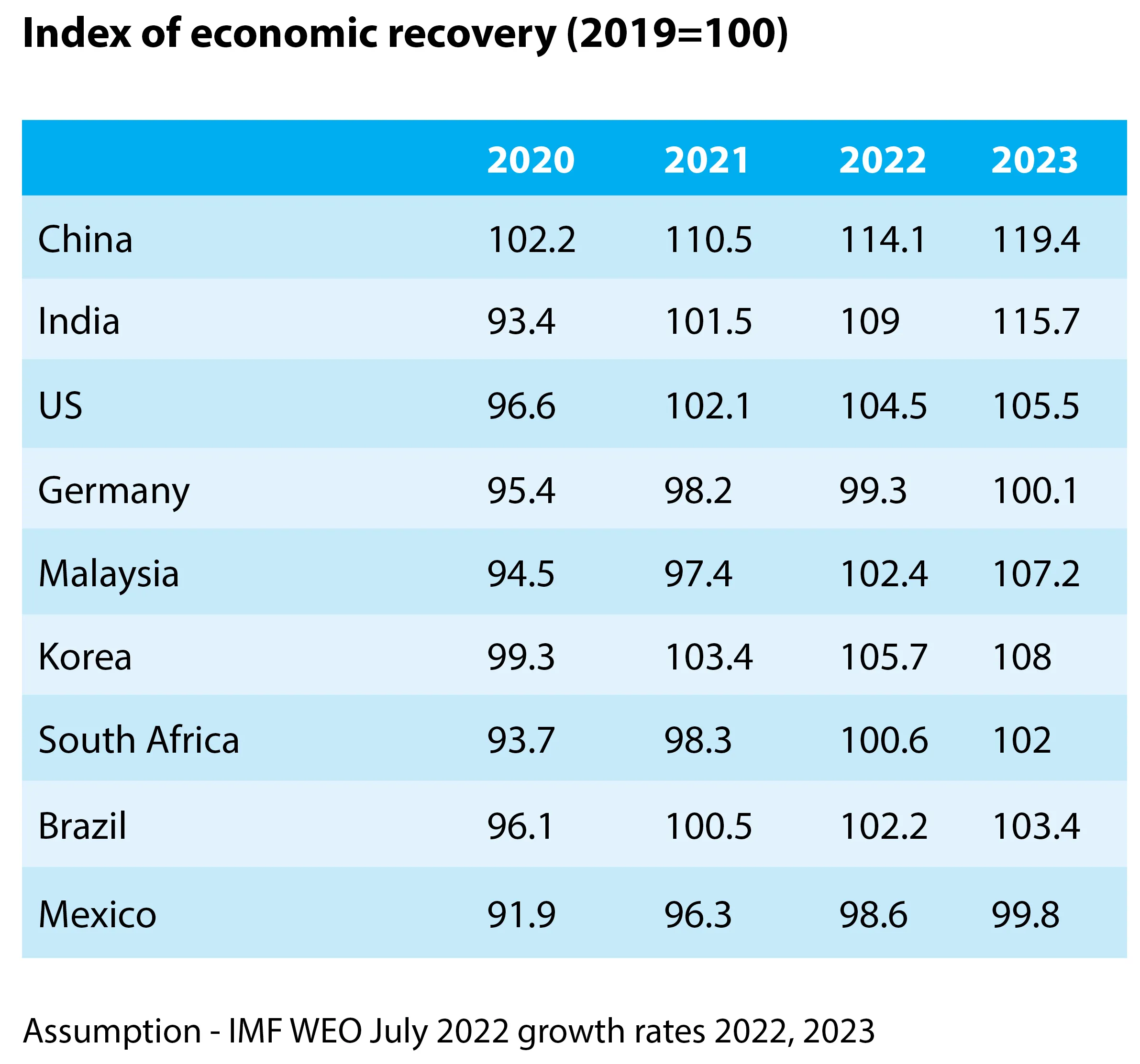

–18—a source of worry for job creation, income, and private investment flow. Nevertheless, the comparative resilience of the Indian economy in bouncing back from the pandemic-linked economic slowdown is illustrated by

recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) data. The table below charts the recovery path for a select list of nine economies out of 38, for which data is available. This list ignores Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Poland and Türkiye

<1> which did not experience a significant slowdown in 2020 but includes China and Korea which did not either—both being popular comparator economies. The recovery index sets 2019 GDP as the base and adds cumulative growth data for each succeeding year till 2023 (IMF projections for 2022 and 2023).

India shows the fastest recovery in real GDP between 2019 to 2022 (addition of 15.6 percent) despite recording the maximum reduction in GDP (of -6.6 percent) in 2020 along with South Africa (6.3 percent). Credit must be given to the growth-sensitive and localised pandemic management arrangements, continued high growth in agriculture, massive welfare payments to insulate the poor from the downturn, stabilised demand, and the accommodative monetary policy which ensured credit availability at lower interest rates.

A dearth of ‘good’ jobs

A continuing disappointment is the lack of adequate job creation—slowing growth being one reason since new investment was deferred. As a last resort, the government had to scrape the barrel and fill 1 million, long vacant and possibly redundant, jobs within its own agencies this year. And this is despite agriculture doing fairly well over the last four years.

Credit must be given to the growth-sensitive and localised pandemic management arrangements, continued high growth in agriculture, massive welfare payments to insulate the poor from the downturn, stabilised demand, and the accommodative monetary policy which ensured credit availability at lower interest rates.

Some of this is structural and expected. The post-1945 expansion in good jobs was due to accompanying efficiency enhancements in processes, innovation in products and services aided by digitalisation, and the international rules-based boom in global flows of finance, tourism, trade, and workers since the 1980s.

This ‘win-win’ arrangement is now broken. Global growth and trade are slowing. The worst affected are low and lower-middle-income economies like India, which have not accumulated the human and capital reserves for sustained growth, relative to the needs of the population. Protection and trade barriers constrain growth but are politically attractive as token ‘active’ economic policies. Brexit is a good example of tokenism driving practicality into isolation.

Demographic trends

Our per capita income is just half of the upper limit of US$ 4255 (World Bank Atlas method) for lower-middle-income economies. The upside is that emigration for work can continue to provide an overseas jobs wedge till our economy grows big enough to accommodate all our workers by 2050. To develop skills compatible with global demand we need to make systemic changes.

First, align syllabi with international standards. Ours, exceed the technical requirements while falling short on practical applications. A graded package of science, technology, mathematics, and basic foreign languages for communication purposes, needs to be rethought, aligning it with future jobs.

Protection and trade barriers constrain growth but are politically attractive as token ‘active’ economic policies. Brexit is a good example of tokenism driving practicality into isolation.

Second, India has 20 universities of excellence authorised to set their own syllabi and adopt pedagogical practices which prepare students for good jobs. Why cannot our government-funded schools, technology training institutes, and universities do the same by seeking collaborations and certification from branded institutions in advanced economies? Unshackling pedagogical innovation, enhancing management autonomy, and promoting international partnerships can improve educational outcomes at a lower cost for the government.

Another noteworthy point is that women are seemingly invisible in our workplaces. Only one-fifth (age cohorts 25 to 59) seek work versus 90 percent of men. Our total fertility rate of 2.2 in 2021 is declining toward the

global TFR of 2.1 children per woman in the childbearing cohorts. It could and should decline faster if more women are to seek work.

A determined overhaul of the reservation policy for women in public service is long overdue. Fiscal incentives (tax rebates) for the private sector to embed gender sensitivity, would have an even larger impact since private employment far exceeds public employment. The all-male 20-member Maharashtra cabinet sworn in on 9 August is an embarrassment, illustrating how far, even a progressive state, has to go in gender equity.

We also need to maintain our demographic dividend. Must we age even before we can graduate to upper-middle-income status? Though India does better (28 per 1,000 live births) than the 2021 global average of 37 in under five mortalities, compare with seven in Sri Lanka, 16 in Vietnam, and 22 in Bangladesh, we are falling behind. A coordinated expansion in nutrition (like fortified rice announced last year) and targeted public health facilities can preserve the baby cohorts providing workers over the next two decades, despite a desirable fall in fertility rates. This prolongs our demographic dividend.

Lok Shakti (People power)

The Prime Minister initiated Gati Shakti last year, a digital platform to integrate infrastructure planning and implementation across silos. Political power suffers from similar fracturing. Local bodies—where ward councillors and panchayat members are in close contact with the poorest of the 250 million households—remain an isolated part of the government, inadequately mandated with powers or finance. That funding and institutional drive matters were demonstrated by municipalities like Mumbai, whilst managing the COVID-19 response and saving lives.

A coordinated expansion in nutrition (like fortified rice announced last year) and targeted public health facilities can preserve the baby cohorts providing workers over the next two decades, despite a desirable fall in fertility rates.

Lok Shakti—the ability to motivate citizens—is intrinsic to local body experience. As per a dipstick survey of the existing Lok Sabha, less than one-third of the members have such experience. Why not revalue local body governance experience by infusing it formally into our disconnected state legislatures and Parliament through a constitutional amendment, prescribing a minimum service of three years as an elected local body representative, as a prior qualification for seeking election as an MLA or MP?

Consider the potential for additional local revenue from empowered local bodies and elected mayors. Revenue from property tax in India was estimated at 0.16 to 0.24 percent of GDP (ICRIER 2011). As per IMF data, the rate is just 0.01 percent of GDP (2015) in India. Vietnam collects 0.04 percent (2015) and Indonesia 0.35 percent (2018). China increased collection from 0.15 percent (2005) to 1.4 percent (2019). Local bodies can generate more than the INR 1.21 trillion allocated for systems revamp by the XV finance commission over five years, simply by taking property tax collections to Indonesian levels of 0.35 percent of GDP.

Bengaluru tripled property tax revenues (1996-2001). Homeowners paid just one-third of the increase. Two-thirds came from better land and building records management, assessment, and collections.

Investment, growth, and government finances can improve only when all vertical and horizontal segments of government are empowered to execute their mandates and executive independence is accompanied by accountability. India is moving. But so is time. The key is to trick time into seemingly stopping, whilst India races ahead—think of it as a national Botox.

<1> The Republic of Türkiye changed its official name from The Republic of Turkey on 26 May 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The annual address from the ramparts of the Red Fort is Prime Minister Modi’s prime vehicle for mass outreach, other than via his Twitter handle. His style—discursive, evocative, and expansive—suits the occasion where substance needs to take a back seat to rhetoric.

All these are good reasons for not looking too deeply into the substance of the speech—unlike, for instance, the annual budget speech of the Finance Minister, but that would be throwing out the baby with the bath water. Throughout his term as prime Minister, his Independence Day speeches chart the evolution of his thinking. The speech and the Prime Minister evolved from simple homilies in 2014 to concrete domestic action in 2015–2017, transitioning over 2018–2021 to shaping long-term national aspirations till 2047.

The annual address from the ramparts of the Red Fort is Prime Minister Modi’s prime vehicle for mass outreach, other than via his Twitter handle. His style—discursive, evocative, and expansive—suits the occasion where substance needs to take a back seat to rhetoric.

All these are good reasons for not looking too deeply into the substance of the speech—unlike, for instance, the annual budget speech of the Finance Minister, but that would be throwing out the baby with the bath water. Throughout his term as prime Minister, his Independence Day speeches chart the evolution of his thinking. The speech and the Prime Minister evolved from simple homilies in 2014 to concrete domestic action in 2015–2017, transitioning over 2018–2021 to shaping long-term national aspirations till 2047.

PREV

PREV