This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

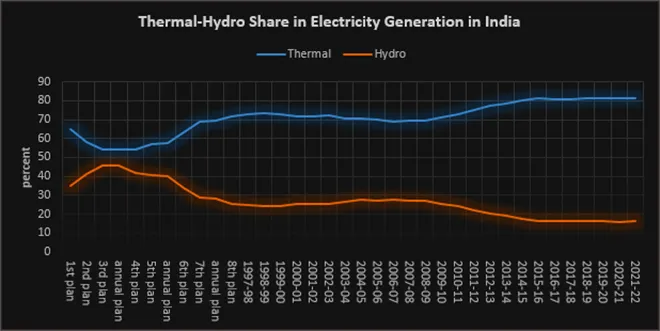

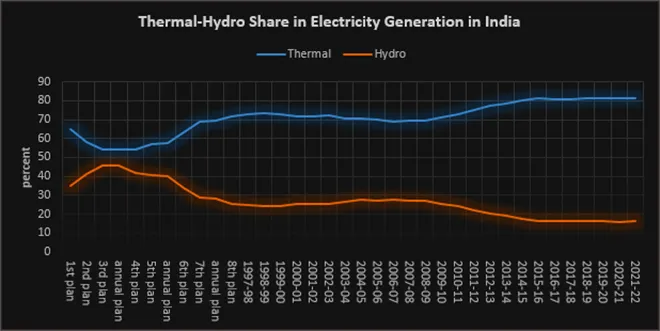

In 1947, hydropower capacity in India was about 37 percent of the total power generating capacity and over 53 percent of power generation. In the late 1960s, growth in coal-based power generation initiated the decline in hydropower’s share in both capacity and generation. In 2022, hydropower capacity of 46,512 MW (megawatts) accounted for roughly 11.7 percent of total capacity. Roughly 12 percent of power generation in 2020-21 was from hydropower.

In the first two decades since independence (1947-67), hydropower capacity addition grew by over 13 percent and power generation from hydro stations grew by 11.8 percent. In the following two decades (1967-1987) hydropower generation capacity grew by over 18 percent but hydro power generation grew only by 5.6 percent. The decline continued in the following decade (1987-2007) with both capacity addition and hydro-power generation growth falling to just over 3 percent. In 2007-2019, hydropower capacity addition grew by just over 1 percent and power generation from hydro-stations grew by under 1 percent. Specific generation or power generated per unit of capacity (a measure of economic efficiency) declined from over 4.4 in the 1960s to less than 2.5 in the early 2000s. Specific generation has improved since then reaching 3.4 in 2019-20.

Local environmental costs

In the last two decades the most significant policy push for hydropower was the 2003 plan for developing 50,000 MW of hydropower capacity. Under the plan, preliminary feasibility reports (PFRs) for 162 new hydro-electric projects were prepared. Out of these, more than half the capacity identified was in Arunachal Pradesh and about a third was in the Himalayan and North-eastern states. As of 2021, only one project of capacity of 100 MW in Sikkim has been commissioned and about 4345 MW capacity is under construction. Twelve projects of total capacity of over 3,500 MW have either been terminated or held up due to local environmental concerns. Forty projects of capacity 13633 MW have either been abandoned or delayed due to local opposition to the projects rooted in local environmental concerns. Only 37 projects got their detailed project reports (DPR) prepared with a decreased capacity of 18,487 MW against 20,435 MW as per the PFR. Seven projects are under survey and investigation; 66 projects are yet to be allotted.

The large body of literature critiquing the construction of hydro-projects in the Himalayan mountains highlight environmental damage imposed on local populations.

In the last few years, many of India’s newer hydro-power projects on the Himalayan rivers (commissioned or under construction) have been damaged by floods and landslides. In some cases, people trapped in project sites have lost their lives or severely injured. The large body of literature critiquing the construction of hydro-projects in the Himalayan mountains highlight environmental damage imposed on local populations. Studies also point out that though recurrent floods are a natural phenomenon, they can be aggravated by anthropogenic interventions. High precipitation in the Himalayas, coupled with the sudden fall in altitude in the mountains of that region results in large volume of water gushing down river channels. Construction of hydro projects and related infrastructure such as roads often aggravate this phenomenon.

Global benefits

In 2020, hydropower contributed to 4,370 Terawatt-hours (TWh) of global electricity generation, the highest contribution by a renewable and low carbon energy resource. Hydropower makes the largest low carbon energy contribution to the global primary energy basket, which is 55 percent higher than that of nuclear power and larger than all other renewable energy (RE) combined. By the end of 2020, there was 160 GW (gigawatts) of pumped storage hydropower installed globally, comprising 95 per cent of all total installed energy storage. Reservoir-based hydropower projects also provide flood control and a dependable water supply for drinking and irrigation purposes.

Many hydropower plants can ramp their electricity generation up and down very rapidly as compared with other power plants such as nuclear, coal, and natural gas. Hydropower plants can also be stopped and restarted relatively smoothly. This high degree of flexibility enables them to adjust quickly to shifts in demand and to compensate for fluctuations in supply from RE sources. Today, hydropower plants account for almost 30 percent of the world’s capacity for flexible electricity supply.

Push for Hydropower

Highlighting the technical and economic benefits of hydropower, the hydro-industry in India pressed for financial incentives from the government to match those received by the RE sector in India given that hydropower was both low carbon and renewable. Hydropower’s ability to rapidly ramp up or down power generation to follow load, meet peak demand, and make up for intermittent generation from RE sources whenever required strengthened the case for incentives from the government. These unique characteristics of hydropower were important in maintaining grid frequency through continuous modulation of active power, control of voltage through the supply of reactive power and the provision of spinning reserves to maintain system stability. As the share of RE in the Indian grid increases, inertia of the grid will decrease which means more hydropower capacity would be required. Hydropower demonstrated these capabilities on the 5th of April 2020 when most households in India switched off electrical lights for nine minutes. The anticipated electricity demand reduction was 12-14 GW but the actual demand loss was over 32 GW for 49 minutes, more than double the demand loss anticipated. Hydro generation stepped in increasing and then decreasing supply within few minutes. At its best hydropower decreased by over 68 percent with a peak ramp rate of 2.7 GW/minute.

The anticipated electricity demand reduction was 12-14 GW but the actual demand loss was over 32 GW for 49 minutes, more than double the demand loss anticipated.

In March 2019, the government approved targeted measures to promote hydropower development in India. This included (i) Inclusion of large hydro power projects as RE sources (until then only projects of less than 25 MW capacity were considered RE sources); (ii) Hydro-purchase obligation (HPO) as a separate category in the non-solar renewable purchase obligation (RPO). The annual targets set based on capacity addition plans were to be notified by the Ministry of Power (MOP) and necessary modifications were to be introduced in the tariff policy; (iii) Tariff rationalization measures including providing flexibility to the developers to determine tariff by back loading tariff after increasing project life to 40 years, increasing debt repayment period to 18 years, and introduction of escalating tariff of 2 percent (iv) Budgetary support for funding flood moderation component of hydropower projects on case-to-case basis for enabling infrastructure i.e. roads and bridges on case to case basis as per actual, limited to ₹15 million/MW for up to 200 MW projects and INR10 million/MW for above 200 MW projects.

The MOP has set the HPO at 0.18 percent for 2021-22 and proposed increase to 2.82 percent by 2029-30. This will increase the demand for hydropower (just as solar purchase obligations increased the offtake of solar power) though not all state distribution companies (discoms) have notified the HPO target. It is estimated that incremental hydropower generation capacity would have to increase by 39 percent or 18 GW to meet HPO obligations by 2030.

Challenges

The hydro industry is hopeful that new financial incentives will add momentum to the hydropower sector. By 2026, roughly 12,340 MW of hydropower capacity addition is planned. Barring a few small projects in central and southern India, most are in the North and North-eastern states. This means reinvigoration of local agitations over environmental compromises. This is justified given that the massive flash floods in Uttarakhand in 2013 caused 5000 deaths, destroyed homes and damaged hydropower projects. There have been many such incidents since then. The 12th plan cautioned that “hydro-power projects on the Himalayan Rivers may not be viable even if they are looked at from a narrow economic perspective”. The Himalayas are relatively young mountains with high rates of erosion. There is little vegetation in the upper catchment to bind soil. High sediment load reduces productive life of power stations through heavy siltation. Judicial intervention following the 2013 floods led to setting up of a committee to investigate future environmental risk recommended cancellation of 23 hydro-projects in the region. Members of the committee from the Central Water Commission, and Central Electricity Authority refused to endorse conclusions of the report from the committee. The enthusiasm for hydropower given its technical capabilities in addressing the challenge of intermittency from the growing share of RE in the grid and in reducing global carbon emissions is understandable. This does not mean local environmental compromises can be dismissed as environmental fundamentalism or anti-developmentalism. The trade-off between the local and global environmental benefits of hydropower are real. The costs are local, and the benefits are global and to some extent national. It is important that the government policy, in its enthusiasm to contribute to the global public good of carbon reduction, does not ignore the cost imposed on the local environment and populations dependent on it.

Source: Quarterly report on Hydropower, Central Electricity Authority 2022

Source: Quarterly report on Hydropower, Central Electricity Authority 2022

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV