Earlier this month, it was reported that New Delhi would be funding 400 full scholarships for Syrian students to study at Indian institutions. To make it a better deal, the Indian government is also reported to have agreed to provide the students with travel honoraria, taking care of their flights out of the embattled country with a shattered economy to come and study in India. Though this came as a surprise to many, it merely underscored a continuation of the Indian diplomatic relations with Damascus, which have been consistent throughout the ensuing civil war in the country since 2011.

India has been one of the few countries that have maintained full diplomatic ties throughout (most of) the Syrian civil war, now in its eighth year, and still nowhere near a conclusion.

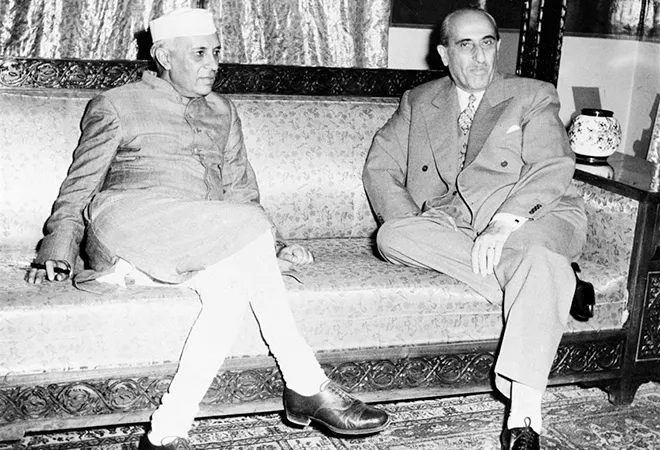

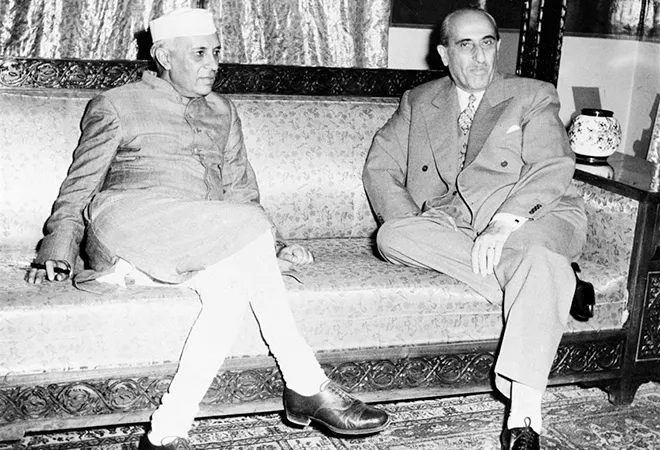

At the Raisina Dialogue 2019 in New Delhi, India’s foreign secretary Vijay Gokhale said that despite a historic perception of India’s foreign policy championing the idea of ‘non-alignment’, one envisioned by the country’s first Prime Minister Jawahrlal Nehru, it is in fact today “aligned”. “The alignment is issue based, and not ideological. That gives us the capacity to be flexible, gives us the capacity to maintain our decisional autonomy.” Over the past few years nowhere else has the impact of this posture more visible than the Indian discourse in West Asia.

India’s approach to its foreign policy via the mandate of ‘strategic autonomy’, as described in brief by Gokhale above, was offered in full view during the Syrian crisis. On the onset of the civil war, in 2011, the regime of President Bashar al-Assad found itself alienated by not just the global community, but perhaps more importantly by its own Arab allies as it was suspended from forums such as the Arab League. Nonetheless, for New Delhi, and via its posture and approach to the Syrian crisis, Assad remained the legitimate government of the embattled country gaining little criticism from India over his government’s actions against their own people.

Diplomatic exchanges between both Damascus and New Delhi have been relatively robust throughout the crisis. Assad’s adviser, Bouthaina Shabaan, made regular trips to India while in 2016, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Mualem visited the Indian Capital and held wide-ranging talks with the Minister of External Affairs Sushma Swaraj. The same year, India’s then Minister of State for External Affairs, MJ Akbar, also visited Syria as part of a trilateral visit of the region. In October 2017, the Grand Mufti of Syria, Ahmad Bader Eddin Mohammad Abid Hassoun, spent five days in India talking about secularism, democracy and even visited Kashmir, saying Kashmir’s power stems from India’s strength. The interesting observation during this period is that despite not having a defined stance on the Syrian crisis other than promoting the idea of immediate ceasefire via talks, all New Delhi did was to continue the diplomatic relations at the same pace as it did before the conflict. There were no major drawdowns, but also no major upraises. “The West puts conditions, the East helps,” the Grand Mufti had added. India also made sure Syrian participation in multilateral forums which it moderated. For example, delegations from Damascus participated in the 2016 3rd Asia Pacific Ministerial Conference on Housing and Urban Development (APMCHUD) in New Delhi. This was a fairly safe and low risk affair to engage Damascus with, while not being a forum that’d attract international ire yet keeping Syria engaged on the bilateral front. On other fronts, it also asserted its commitments to the long-standing development projects in the country.

Other than a brief period in the middle when the Indian embassy in Damascus did not have an Ambassador, on the back of increasing security concerns and, as per some with knowledge, not many within the diplomatic pool were very keen to take up the assignment at that point of time, leaving an Indian security official from one of the police forces as the charge d affaires.

However, the Indian presence and perception, seen as a neutral, non-aligned country and one that has had good ties with the Assad family over the past few decades, was a constant. While Syria is being taken as an example for this piece, the effects of this diplomatic footing over the past many decades has been exploited positively by the global community as well. For example, the P5+1 countries, during the arduous process of the Iran nuclear negotiations, also used New Delhi’s goodwill in Tehran to convince the Iranian government to accept a deal.

The fact that Indian presence almost always means reliance on soft power rather than hard power, a historical product of idealism fueled by an impoverished economy, it often finds itself able and capable to conduct diplomacy with states that are either isolated or at odds with the so-called ‘great powers’ of the global order. New Delhi’s good relations with both Washington D.C. and Moscow, despite its slant towards the Russian discourse on Syria, was largely irrelevant to the general global discourse on the crisis. However, once the clouds of war (relatively) subsided and now that it is largely accepted that Assad will remain at the helm in Damascus (with continuous help of Russia and Iran), the capabilities of Indian outreach were showcased after the Indian embassy organised Yoga Day celebrations not only in the capital but also in Aleppo, which only months ago was the de-facto capital of the so-called Islamic State’s caliphate.

Last year, India became the first country to hold an open air event since the fall of the caliphate’s hold on Aleppo, despite the city being in almost complete ruins. Sanskrit chants were recited amidst the rubble, which coincided with azaan from the local mosque, to highlight the messages of peace and unity.

India’s diplomatic outreach in the West Asia is riddled with both successes and failures, but events such as Syria over the past few years, the evacuation of Indians and foreigners alike from Yemen, its bullishness over protecting its bilateral relations with Iran against the reinstatement of US sanctions offer a good view of how its diplomacy has operated in the region. India’s ability to conduct robust diplomatic engagements over the past decade with the GCC, Iran and Israel -- the three main poles of regional power structure -– underlines a sound model on how ‘strategic autonomy’ can be effectively operationalised. Such an approach may be the only viable option for India as it attempts to counterbalance an increasingly assertive China, not just in the region, but around the world, with an increasingly volatile global order taking shape around the country’s celebrated growth story.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV