This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2021.

December 2020 marked the fifth anniversary of the Paris Agreement; at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris, France, in 2015, world leaders succeeded in agreeing on a comprehensive, ambitious and universal global pact on climate change. In the lead-up to COP21, a number of developed countries and multilateral institutions made significant climate finance pledges. The outcome of COP21 further urged developed countries to scale up their level of financial support, with a concrete roadmap to achieve their US$ 100-billion-a-year commitment by 2020. Less than 10 years remain to cut emissions by nearly half if we are to have a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions will need to be reduced by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching “net zero” around 2050. The “decade of action” in support of climate and other sustainable development goals (SDGs) has begun, but much remains to be done.

Despite progress, atmospheric CO2 concentrations continue to increase. Global average temperatures in 2020 were tied for the hottest on record, capping what was also the planet's hottest decade ever recorded. The year 2020 also topped the previous record in terms of number of billion-dollar weather and climate disasters.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions will need to be reduced by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching “net zero” around 2050.

In the near term, the priority will be to address the health, economic and societal crisis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, and to ensure a durable and resilient economic recovery from this crisis. Yet, a return to “business as usual” and environmentally detrimental investment activities must be avoided; the world must commit to ‘building back better’ and stepping up actions for a sustainable and inclusive recovery.<1>, Countries and regions have already made important steps towards that; for instance, South Korea’s Green New Deal or the European Green Deal.

Achieving climate objectives requires an unprecedented acceleration of financial flows into climate-aligned investments, and a massive shift away from investments in emissions-intensive activities. While ramping up efforts for a resilient, sustainable and inclusive recovery, the transition to a green economy must be accelerated. With many countries aiming to achieve carbon-neutrality by mid-century, private finance for green investment must be leveraged, with governments playing a critical role in this effort. Addressing climate change will require a significant increase in green finance and investment at a time when investment is falling sharply. Achieving the objective agreed in the Paris Agreement — limiting global temperature increases to well below 2°C from pre-industrial levels — requires all forms of finance, whether private, public or blended finance. Mainstream private finance is particularly indispensable to help companies realign their business models towards net-zero emissions pathways.

India’s nationally determined contribution estimates that the country will require around US$ 170 billion per year for climate action.

Take India, for instance. In 2019, India announced an ambitious target to reach 450 GW of renewable power by 2030. India’s nationally determined contribution estimates that the country will require around US$ 170 billion per year for climate action. There are some positive signs — FDI in India increased by 13 percent in 2020 and the country has a fast growing energy sector. A recent study estimates that in 2018, India received green financing worth US$ 21 billion. Still, it is clear that meeting India’s climate and other sustainability goals will require a significant scaling up of investment, including from private sources of finance.

The good news is there is no shortage of available capital globally. Institutional investors in OECD and G20 countries alone have at least US$ 64 trillion of assets under management — and under the current investment regulations in OECD and G20 countries, pension funds and insurance companies can allocate up to US$ 11.4 trillion towards infrastructure.<2>, Environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing and broader sustainable finance have also rapidly increased in the past few years. Positive developments include the initiatives such as the Financial Stability Board’s industry-led Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the development of sustainable finance taxonomies and definitions in Asia and elsewhere to guide financial decisions, and the growth in green bonds issuance. Since the first issuance of green bonds by Yes Bank in 2015, India has emerged as the second-largest emerging green bonds market, with US$ 7.2 billion in issuance, most of which has been used to fund renewable energy projects. Yet, issuance so far remains too small to meet the country’s green finance needs.

Institutional investors in OECD and G20 countries alone have at least US$ 64 trillion of assets under management — and under the current investment regulations in OECD and G20 countries, pension funds and insurance companies can allocate up to US$ 11.4 trillion towards infrastructure.

Unfortunately, the world is still a long way from aligning financial flows with the Paris climate objectives. The lion’s share of financing is not yet sustainable, even though making infrastructure climate-compatible will require only a 10 percent incremental increase in expenditure over known levels. A new OECD empirical study of institutional infrastructure investment shows that institutional investors hold only US$ 314 billion in green infrastructure, out of US$ 1.04 trillion in infrastructure assets.<3>, As for international climate finance flows, OECD analysis highlights that donor countries need to urgently step-up efforts to provide public climate finance and improve its effectiveness in mobilising private finance. These efforts must further support developing countries to respond to the immediate effects of the pandemic and to integrate climate actions into each country’s recovery from the COVID-19 crisis to drive sustainable, resilient and inclusive economic growth.

Countries are also far from addressing the global loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services, which are being destroyed at an unprecedented and accelerating rate, with 25 percent of all plant and animal species now threatened with extinction. Protecting biodiversity is also vital to avoid the next pandemic. COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, as are nearly two-thirds of infectious diseases. The pandemic has underscored the importance of environmental health and resilience as a critical complement to public health. Yet, investors’ and businesses’ awareness of and commitment to biodiversity action remain too limited. This is despite a few encouraging initiatives to build momentum in the lead-up to fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, such as the future Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures.

Protecting biodiversity is vital to avoid the next pandemic.

If sustainable finance is to be environmentally sustainable, it must assess and manage its impact on the environment instead of only considering the financial risks posed by environmental factors. In the lead up to COP26, the shift towards a financial system that fully considers its own climate (and biodiversity) impacts on people and the planet must be accelerated. There needs to be improved assessment, management and disclosure of corporates’ and financial actors’ adverse climate (and biodiversity) impacts and risks on society and the planet, from an environmental materiality perspective.<4> More broadly, much more work is needed to align the entire financial system with environmental and social goals, as stressed in ongoing OECD work with the United Nations Development Programme and other key actors on SDG-aligned finance.

Creating real impact

Good progress has been made worldwide on disclosing the risks that climate change poses for financial returns, i.e. from a financial materiality perspective.<5> An increasing number of central banks, financial supervisors, and individual investors, insurers and financial institutions are trying to better understand and emphasise the economic and financial impact of climate-related financial risks (particularly physical and transition risks), and to develop climate scenario analysis and stress tests to better assess and manage these risks. This is partly thanks to momentum amongst financial regulators generated by the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, in which the OECD is an observer, as well as a transition in thinking amongst investors based on the implementation of TCFD recommendations.

Policy interventions, incentives and, more broadly, low-emissions resilient transition trajectories will depend on countries’ national circumstances and priorities.

Yet, making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development, as called for under Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, requires that policymakers, standard setters, investors and finance providers pay far greater attention to the climate impacts of finance in the real economy, society and the planet. Of course, governments need to set the right incentives in the real economy to redirect finance away from emissions-intensive projects, and provide policy frameworks consistent with a transformational — not incremental — approach to decarbonising the economy. It is important to note here that policy interventions, incentives and, more broadly, low-emissions resilient transition trajectories will depend on countries’ national circumstances and priorities. Variability between regions and individual economies is desirable to ensure broad consensus and the successful delivery of global commitments. But beyond the need for tailored policies in the real economy, given the systemic nature of climate change and other environmental goals, changes are needed in how the global financial system works to deliver the financing needed to transition to a green economy and sustainable development.

The financial market must pay increased attention to the choice of metrics used across asset classes and investment mandates from the standpoint of environmental materiality. Whether in setting climate disclosure standards, ESG indices or benchmarks, or green bond standards, environmental impact is central to achieve sufficient emission reductions and climate resilience in the coming decade. The latest proposal by India’s Securities and Exchange Board on mandatory business responsibility and sustainability reporting is an appreciable step towards better assessing the environmental materiality of financial decisions.

The financial market must pay increased attention to the choice of metrics used across asset classes and investment mandates from the standpoint of environmental materiality.

Ensuring the financial system addresses its adverse climate and other environmental impacts will also help focus attention on issues of greenwashing in sustainable finance. For example, although green bonds continue to be a focal point for green finance, a 2020 study by the Bank for International Settlements indicates that “green bond projects have not necessarily translated into comparatively low or falling carbon emissions at the firm level.” Similarly, while ESG investing assets now account for trillions of dollars and have increased during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, its climate benefits are unclear at best. For example, a 2020 OECD report found that several highly rated ESG portfolios actually have higher total CO2 emissions and carbon intensity than traditional market weighted portfolios.

|

Inter-related concepts of environmental materiality, alignment, and impact

Financial materiality addresses environmental factors where such factors may have an impact on the financial performance of a company or on the broader financial stability of the financial system. Taking an “outside-in” perspective, financial materiality considers the (internal) impacts that environmental (and social) factors may have on a company’s financial performance. In contrast, the concept of environmental (and social) materiality takes an “inside-out” perspective. It focuses on the adverse (external) impact of a corporate or investment decision on society and the environment, in terms of environmental (and social) factors. For an increasing number of investors and other stakeholders, managing climate risks and adverse impacts on society and the planet requires assessing the misalignment of portfolios with climate goals, and aligning portfolios with such goals.

Beyond the notion of impact, the word materiality also implies a degree of relevance, level or sufficiency. In the financial materiality context, an investor considers whether a particular risk factor has a sufficiently “material” impact on financial performance to warrant assessment and disclosure. In the context of corporate and investor disclosure, the environmental materiality concept encompasses the relevance and sufficiency of corporate and investor actions to reduce negative environmental impacts and risks in light of broader environmental goals. In the context of sustainable finance standards, taxonomies and definitions (as well as the emerging area of transition finance), environmental materiality encompasses whether investments are sufficiently aligned with key environmental objectives to merit or qualify for the use of a particular label. For example, the EU requires that only those green bonds (issued or sold in the EU) that finance economic activities aligned with the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy, are sufficiently green to receive the EU green bond label. The Taxonomy criteria are aligned with the EU’s goal of climate neutrality by 2050, which in turn can be understood to encompass a regional pathway and underlying national and sectoral pathways. Thus, judgements on what is sufficiently green — or what might be sufficiently stringent to qualify for a future “transition finance” label, for example — are multi-faceted and complex to assess.

Sources: Dobrinevski, A. and R. Jachnik (2020); European Commission (2021); European Union (2020); European Commission (2019); IMP (2020). |

Of course, climate change is not the only environmental challenge for which significantly increased scrutiny on the environmental impacts of finance is urgently needed. Biodiversity loss and water-related challenges are existential challenges for humanity, and yet the environmental impacts of finance are only beginning to be explored in detail, particularly for biodiversity. So far, the biodiversity finance agenda has largely been driven by the public sector,<6>, for instance, with India’s National Biodiversity Finance Plan launched in 2019. Yet, scaling up private finance in support of biodiversity action will be critical to achieve biodiversity goals. And investors, issuers and corporates need to better integrate biodiversity factors (including risks, impacts, dependencies and opportunities) in their decisions.

As sustainable finance has begun to merge with mainstream finance, fragmentation, a lack of transparency or the risk of greenwashing can be seen in various areas.

In addition, strong growth in ESG investing and broader sustainable finance have encouraged a proliferation of disclosure frameworks, metrics, rating methodologies and investment approaches, which creates further challenges to ensure that sustainable finance delivers on environmental materiality and impact. Currently, ESG practices vary so widely that they lack clear alignment not only with financial materiality (and there is little evidence that risk adjusted returns have kept pace over the past decade) but also with societal and environmental objectives. Indeed, as sustainable finance has begun to merge with mainstream finance, fragmentation, a lack of transparency or the risk of greenwashing can be seen in various areas. These include sustainable finance definitions, ESG methodologies and metrics, sustainability and integrated reporting metrics, sustainable infrastructure standards, and the emerging area of climate transition finance. Importantly, steps to harmonise financial and sustainability reporting have only just begun, and while there is a wealth of ESG data available, it is not consistent, comparable or easily verifiable. Policymakers must step up to make sustainable finance practices fit for purpose by working together towards a global, mandated, auditable sustainability reporting framework, including to drive better transparency and standardisation of the core elements of environmentally (and socially) sustainable disclosure. Policymakers can also strengthen the regulatory environment, including regulatory guidance on data disclosure and appropriate labelling of sustainable finance products to ensure their link to the double materiality is clear, in addition to defining long-term financial materiality to better capture slower-moving environmental and social risks.

There is already an international legal instrument to help businesses, investors and other financial actors undertake and report on environmental and social due diligence, namely the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (the Guidelines). The Guidelines, and related due diligence guidance<7> for corporates and investors, focus primarily on social and environmental materiality. The Guidelines are the only multilaterally-agreed and comprehensive code of Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) that governments have committed to promoting, representing international consensus on the responsibility of businesses regarding impacts on society and the environment. The Guidelines are adopted by all OECD members and 12 non-member countries, and are open for adherence to interested non-OECD members. These countries represent some of the largest markets in the world and a large majority of global trade and investment activity. Climate, biodiversity and other environmental considerations explicitly fall under the scope of the Guidelines, but no practical guidance has been developed yet to support the implementation of RBC and due diligence for climate change or biodiversity specifically.

India is part of the EU International Platform for Sustainable Finance to advance environmentally sustainable finance, along with 16 other members accounting for 55 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, 50 percent of the world population, and 55 percent of global GDP.

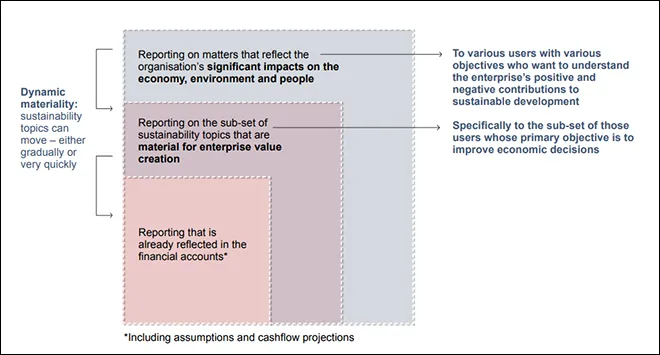

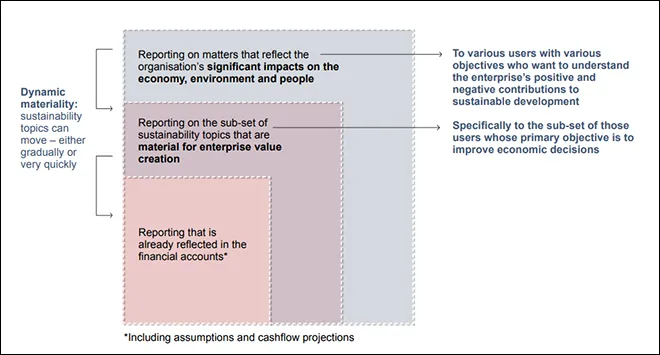

In addition, environmental materiality and due diligence are gaining traction as an important complementary lens through which to consider sustainability factors, although it is important to recognise that national circumstances may differ worldwide. The EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive, for instance, has a double materiality approach, and the EU’s disclosure obligations under the Sustainable Finance Taxonomy regulation are introducing a focus on the environmental impact of economic activities, which may impact Indian companies seeking to attract EU-based investment. India is part of the EU International Platform for Sustainable Finance to advance environmentally sustainable finance, along with 16 other members accounting for 55 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, 50 percent of the world population, and 55 percent of global GDP. In Asia, examples of recent environmental due diligence regulations include Japan’s guide for environmental due diligence along value chains. Worldwide, five framework- and standard-setting institutions<8> have published a shared vision of the elements necessary for more comprehensive corporate reporting that consider environmental material factors as part of a “dynamic materiality” approach (see Figure 1). The IFRS Foundation’s 2020 consultation paper on sustainability reporting suggests that a new Sustainability Standards Board could consider how to extend its scope beyond financial materiality in light of evolving stakeholder views. The OECD stressed the importance of considering double materiality in its response to the IFRS Foundation Consultation on Sustainability Reporting, along with the need for greater coordination to standardise sustainability disclosure practices.<9>, Several investors, issuers and other financial institutions have stressed a similar message to the IFRS Foundation.

Figure 1. Dynamic materiality

Sources: CDP et al. (2020); WEF (2020).

Sources: CDP et al. (2020); WEF (2020).

The Paris Agreement has also stimulated a wide range of activities on how finance might be better aligned with climate goals. For several years, the OECD-led Research Collaborative on Tracking Finance for Climate Action has been producing analyses and organising workshops that contribute to increasing the knowledge base on climate finance and climate alignment of investments and financing. An increasing number of stakeholders are recognising the need to align portfolios with climate goals to manage climate risks and adverse impacts on society and the planet, from an environmental materiality perspective. Though country contexts differ, several financial stakeholders are also increasingly recognising the need to go beyond a pure financial stability, financial materiality or pure risk management approach, towards a precautionary, market-shaping approach in support of broader climate alignment goals. In August 2020, the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, for instance, launched a Net Zero Investment Framework for consultation, as part of the Paris Aligned Investment Initiative, to explore how investors can align their portfolios with the goals of the Paris Agreement. And as part of the COP26 private finance strategy, environmental materiality issues are being discussed in the guise of ongoing work on portfolio alignment with climate objectives.

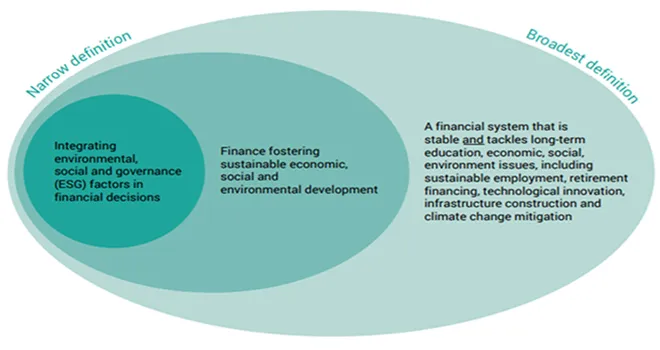

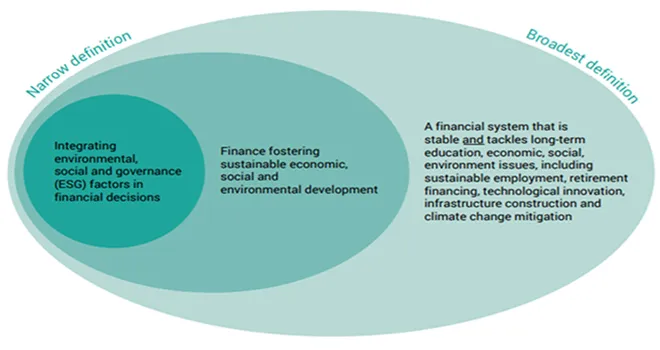

Figure 2. Three definitions of sustainable finance

Source: EU HLEG (2017).

Source: EU HLEG (2017).

The next few years will be critical to ensure the financial system is fit for purpose to deliver the financing needed to achieve environmental and other SDGs. Beyond a narrow definition of sustainable finance as merely integrating ESG factors in financial decisions, the broadest definition of sustainable finance is “a financial system that is stable and tackles long term education, economic, social, environment issues” (see Figure 2). In the past decade, the OECD has worked to mobilise private finance for sustainable investment, including through analytical work and engagement under its Centre on Green Finance and Investment and its annual flagship event, the OECD Forum on Green Finance and Investment, which took place virtually in October 2020, with 3800 registered participants, including 500 from 23 Asian countries. As its contribution to this global effort, the OECD plans to initiate analytical work on the climate and environmental materiality, alignment and impact of finance. Foreseen research and analytical work include projects on the environmental materiality of metrics used in financial and non-financial disclosures; climate alignment assessments of finance; emerging approaches to climate transition finance; and environmental and climate due diligence process and risk management tools, building on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

This article has benefited from very substantial inputs from Robert Youngman (team leader, Green Finance and Investment, OECD) as well as useful inputs from other OECD colleagues, including Simon Buckle, Beth del Bourgo, Raphael Jachnik, Aayush Tandon, Barbara Bijelic and Cecilia Tam.

<1> As part of its support the green recovery, the OECD is currently updating and refining its database tracking the environmental dimensions of recovery measures. The database and further analysis can support governments in setting the right signals to attract private finance for sustainable investments.

<2> In investable assets under management (AUM)

<3> Excluding corporate stocks, even of infrastructure-related corporations

<4> i.e., material adverse impacts and risks on people, the environment and society, resulting from investment and business decisions.

<5> i.e., the material risks to financial performance and broader financial stability resulting from climate change.

<6> Based on currently available data, global biodiversity finance is estimated at US$ 78-US$ 91 billion per year (2015-2017 average), including US$ 67.8 billion per year in public domestic expenditure, US$ 3.9-US$ 9.3 billion per year in international public expenditure, and only US$ 6.6-US$ 13.6 billion per year in private expenditure on biodiversity

<7> Including the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct; the OECD report Responsible Business Conduct for Institutional Investors, and forthcoming supplement to this report to analyse what the OECD Guidelines and the Due Diligence Guidance means for institutional investors in terms of climate risks to society and the environment.

<8> The CDP, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board, the Global Reporting Initiative, the International Integrated Reporting Council and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board.

<9> The OECD’s response to the consultation states that, “the OECD supports efforts by the SSB to consider how to broaden its scope as it proceeds with its work, while working with other initiatives, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the risks and opportunities for a reporting entity.”

Angel Gurría, “The Paris Agreement 5 years on: Taking stock and looking forward,” OECD, 11 December 2020.

Valérie Masson-Delmotte et al., eds, Global Warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, IPCC, 2018.

Sustainable Development Goals, “Decade of Action,” United Nations.

“2020 Tied for Warmest Year on Record, NASA Analysis Shows – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet,” NASA, 14 January 2021.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 1980 - present, NCEI, 2021.

“Making the green recovery work for jobs, income and growth,” OECD, 6 October 2020.

“Making the green recovery work for jobs, income and growth”; Donald Kirk, “Korea Reveals ‘New Deal’ Designed To Boost Jobs, Revive Sagging Economy,” Forbes, 14 July 2020.

Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth (Paris: OECD Publishing, 23 May 2017).

Mark Carney, Building a Private Finance System for Net Zero: Priorities for private finance for COP26, COP26, UN, 2020.

Climate Polivy Initiative, Landscape of Green Finance in India, CPI, 2020.

UNCTAD, “Investment Trends Monitor,” UNCTAD, 2021.

“Landscape of Green Finance in India”

Green Infrastructure in the Decade for Delivery: Assessing Institutional Investment, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 6 October 2020).

“The US SIF Foundation’s Biennial “Trends Report” Finds That sustainable investing assets reach USD 17.1 trillion,” US SIF 16 November 2020.

Developing Sustainable Finance Definitions and Taxonomies, (Paris: OECD Publishing, Paris, 6 October 2020).

“Yes Bank issues India’s first green bond,” Climate Home News, 19 February 2020; Monica Filkova, Camille Frandon-Martinez and Amanda Giorgi, Green bonds: The state of the market 2018, Climate Bonds Initiative, 2019.

Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth

Green Infrastructure in the Decade for Delivery

Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-18, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020.

“Biodiversity and the economic response to COVID-19: Ensuring a green and resilient recovery,” OECD, 28 September 2020.

Edward Perry, “Time for Nature: Is a global public health crisis what it takes to protect the planet’s biodiversity?” OECD Environment Focus Blog, 5 June 2020.

“Environmental health and strengthening resilience to pandemics,” OECD, 21 April 2020.

TNFD, “Bringing Together a Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures,” TNFD.

OECD SDG reporting Framework, (Paris, OECD Publishing, 2021).

Mark Carney, Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon - Climate change and financial stability - speech by Mark Carney (speech, London, 29 September 2015), Bank of England.

UNFCCC, Paris Agreement, UNFCCC, 2015.

Raphaël Jachnik, Mariana Mirabile and Alexander Dobrinevski, “Tracking finance flows towards assessing their consistency with climate objectives,” Paris, OECD Environment Working Papers, no. 146, 19 Mar 2019.

OECD, The World Bank and UN Environment, Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure, Paris, OECD Publishing, 2018.

“Financing Climate Futures”

SEBI, Consultation Paper on the format for Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting, SEBI, 18 August 2020.

Torsten Ehlers, Benoît Mojon and Frank Packer, “Green bonds and carbon emissions: exploring the case for a rating system at the firm-level,” BIS Quarterly Review (September 2020).

“The US SIF Foundation’s Biennial “Trends Report” Finds That Sustainable Investing Assets Reach $17.1 Trillion”

Riccardo Boffo, Catriona Marshall and Robert Patalano, ESG Investing: Environmental Pillar Scoring Reporting, OECD, 2020.

Alexander Dobrinevski and Raphaël Jachnik, “Exploring options to measure the climate consistency of real economy investments: The transport sector in Latvia,” Paris, OECD Environment Working Papers, no. 163, 2020; European Commission 2021, “EU taxonomy for sustainable activities,” European Commission, 2021; European Union, “EU Regulation 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088,” Official Journal of the European Union, 2020; European Commission (2019), Guidelines on non-financial reporting: Supplement on reporting climate-related information, European Commission, 2019; Impact Management Project, Reporting on enterprise value: Illustrated with a prototype climate-related financial disclosure standard, IMP, 2020.

OECD, A Comprehensive Overview of Global Biodiversity Finance A Comprehensive Overview of Global Biodiversity Finance, OECD, 2020.

“India’s Biodiversity Finance Plan launched on International Biodiversity Day,” BIOFIN, 24 May 2019.

Biodiversity: Finance and the Economic and Business Case for Action (Paris: OECD Publishing, 6 December 2019).

OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2020: Sustainable and Resilient Finance, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 29 September 2020); OECD, Environmental social and governance (ESG) investing, OECD, 2020.

“ESG Investing”; “Environmental social and governance (ESG) investing”

OECD, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition, Paris, OECD, 2011.

“OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition”

OECD “Promoting Responsible Supply Chains in Japan,” OECD, 2020.

OECD, OECD Response to the IFRS Foundation Consultation on Sustainability Reporting, OECD, 2020.

Carlos Tornero, “IFRS sustainability project a “backward step” without double materiality at its core - Federated Hermes,” Resposible Investor, 22 December 2020.

CDP, CDSB, GRI, IIRC and SASB, “Statement of Intent to Work Together Towards Comprehensive Corporate Reporting,” September 2020; World Economic Forum, “Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation,” WEF, 22 September 2020.

OECD, “Research Collaborative: Tracking Finance for Climate Action,” OECD; OECD, “Workshop on measuring the alignment of investments and financing with climate objectives,” OECD, 7 October 2020.

IIGCC, Net Zero Investment Framework for Consultation, IIGCC, 2020; IIGCC, IIGCC Net Zero Investment Framework: Consultation Response, IIGCC, 2021.

EU HLEG, Interim report of the High-Level Expert Group on sustainable finance - Financing a sustainable European economy, EU HLEG, 2017.

OECD, “Centre on Green Finance and Investment,” OECD.

Ben Caldecott, “Defining transition finance and embedding it in the post-Covid-19 recovery,” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment (28 July 2020): pp. 1-5.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sources: CDP et al. (2020); WEF (2020).

Sources: CDP et al. (2020); WEF (2020). Source: EU HLEG (2017).

Source: EU HLEG (2017). PREV

PREV