This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Background

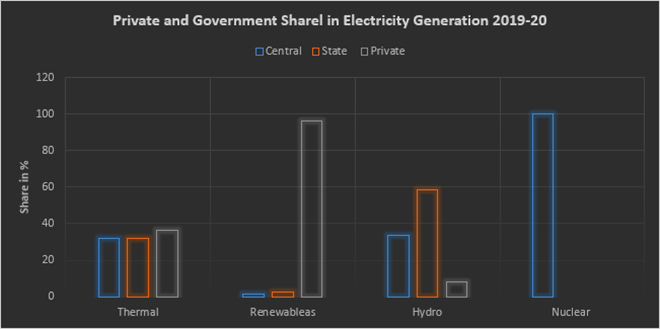

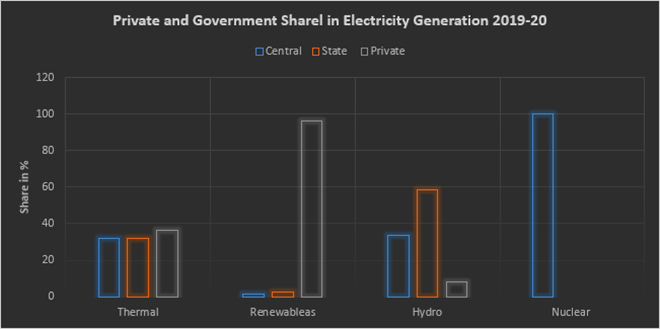

The executive director of the IEA (International Energy Agency) remarked in 2021 that hydropower was the forgotten giant of clean electricity and that it needs to be put squarely back on the energy and climate agenda if countries are serious about meeting their net-zero goals. This is an important message for India where the share of hydropower capacity and its share in a total generation is in terminal decline. In 1947, hydropower capacity was about 37 percent of the total power generating capacity and over 53 percent of power generation. In 2021-22, the share of hydropower generation capacity (not including small hydropower and pumped storage) was just over 11 percent and its share in power generation was also just over 11 percent of the total. To increase investment in the hydropower sector and facilitate growth, the government opened hydropower generation to the private sector in 1991. However, the share of the private sector in hydropower generation capacity is less than 10 percent today, the lowest compared to over 96 percent in the renewable energy sector and 36 percent in the thermal power generation segment.

Phases of Hydropower Development

From 1947-67, hydropower capacity development grew by over 13 percent and power generation from hydropower stations grew by 11 percent. This was a period of state-led growth in constructing large multipurpose storage dams. The state-sponsored the construction of large dams, labelled ‘temples of India’, for providing irrigation and for generating electricity. In the two following decades (1967-87) hydropower capacity development grew by 18 percent but generation grew by just over 5 percent. In this period, rapid scaling up of coal-based power generation started displacing hydropower generation and most of the large dams built were used for canal-based irrigation. Groundwater pumping accelerated across the country driven by electricity tariff subsidies at the state level, but it was coal that supplied most of the power. The decline in hydropower capacity development continued from 1987-2007 with both the growth of capacity addition and generation falling to about 3 percent. Social and environmental opposition to large dams that started in the 1980s gathered momentum in this period. Though hydro-power generation was open to the private sector both capacity addition and generation fell to about 1 percent in 2007-2019.

The share of the private sector in hydropower generation capacity is less than 10 percent today, the lowest compared to over 96 percent in the renewable energy sector and 36 percent in the thermal power generation segment.

Enabling Policies

Since the partial liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, a series of policies that enabled the entry of the private sector in hydropower generation was implemented. In 1991, hydropower generation was opened to the private sector and a 16 percent return on equity was allowed in 1992. In 1998 the hydropower policy was formulated to facilitate the development of hydropower projects in the North and Northeast of the country that held huge potential. In 1995, the government issued a notification providing a two-part tariff for hydel generation stations that addressed some of the concerns of private developers. The notification of the electricity act 2003, the national electricity policy 2005 and the tariff policy 2006 favoured private investment in electricity generation. The 2007 policy for rehabilitation and resettlement of people affected by industrial projects addressed one of the key concerns over hydropower projects. In 2003, the government launched the 50,000 MW hydropower initiative to expedite hydropower development. The policy intended to fast-track land acquisition and environmental clearances. This central government policy was followed by several state-level policies to promote private sector participation in hydropower development, with state electricity boards (SEBs) retaining authority to select developers to execute projects. In 1996, all hydro projects estimated to involve a capital expenditure above INR 1 billion required techno-economic approval from the central electricity authority (CEA) later raised to INR 2.5 billion. For projects selected by state government bodies through competitive bidding, the exemption limit for CEA techno-economic clearance was raised to INR 10 billion. This long rope offered to the private sector-led to the embrace of run-of-the-river (RoR) projects.

Role of the Private Sector: Run of the River Projects

In theory, RoR hydropower projects, unlike traditional hydropower schemes, do not impound water behind a dam in a large reservoir and work with the natural flow of the river. They make use of the natural flow of the running water by diverting it through tunnels over a certain elevation drop to generate power. The water is then released into the river channel after power generation. The absence of a large reservoir avoids the displacement of local communities. The use of natural flow, likewise, is considered to have a limited impact on the ecology of the river. For the private investor RoR hydro projects translated into lower capital costs (compared to storage dams), lower lead times, and less conflict with the local environment and the local population. Most importantly it meant attractive revenue streams would start flowing much earlier than in the case of storage dams. India’s Hydropower Policy 2008 contained a number of generous concessions, that insulated private companies from the majority of the hydrological and financial risks inherent to the sector. These risks were transferred to the public maximising the margin for profits for the private developer by raising the costs of power. The tariff regime for hydropower gave power producers no economic incentive to optimize project designs according to comprehensive hydrological data. Private developers projected high-capacity potential for projects as they were to be paid for full “design energy” generation, even when water is scarce and power generation is low, whilst buyers pay more for less electricity.

For the private investor RoR hydro projects translated into lower capital costs (compared to storage dams), lower lead times, and less conflict with the local environment and the local population.

The Himalayan states rushed into awarding hydro-power projects to private developers through what came to be known as the MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) route. Experienced and inexperienced private developers aggressively competed with each other to win projects from Himalayan states expecting windfall profits from favourable policies. The press reported that the expectation of hydro-dollar wealth had resulted in the MoU virus taking over the Himalayan states. About a decade later, private developers were competing with each other once again to walk out of hydro-projects as positive assumptions over environmental, social and financial outcomes proved to be false.

Issues

The private sector often portrays the entrenched role of the government in the Indian energy sector as a liability. However, the private sector leveraged government dominance over the energy, water and environmental sectors at the central and state levels to enter a new relatively high-risk sector such as hydropower generation. The presence of the government enabled the ‘socialisation’ of the environmental, social and economic cost of hydro-projects essentially minimising risks for private investment. The use of contracts and auctions rather than open markets to attract investment enabled the marginalisation of expert opinion on environmental issues, hydrological challenges and social participation. The costs determined contractually were passed through to consumers administratively rather than through responsive price mechanisms.

The government’s rush to meet ambitious targets for decarbonisation that enhances its global prestige is following roughly the same route of minimising risk and maximising reward for the private sector involved in renewable energy projects. Only time will tell if the private sector eventually decarbonises India’s energy system and provide abundant and affordable clean energy to all.

Source: tndindia.com

Source: tndindia.com

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV