Europe and the European Union are divided more than ever, specifically on the Russian threat against Ukraine. Europe for a large part in the ongoing conflict has assumed the role of a bystander which is due to culmination of disunity, inability, and historical dependence on the US for European security. The Russia–Ukraine crisis for Europe comes in comprising circumstances as the UK Prime Minister is surrounded by domestic scandal; France begins its preparation for its Presidential Elections due in April; the new German coalition government is yet to find their unified voice against Russia; and Eurozone is encountering increasing inflation largely due to higher energy prices. Additionally, Europe has been dealing with an energy crisis for the past several months which has led to rising energy prices. The contentious circumstances in Europe have unequivocally outsourced security and diplomatic efforts to Washington. The transatlantic relationship over the years has become skewed and asymmetrical largely dictated by the US.

The collaborative military defence spending dropped from €5.5 billion in 2017 to €4.1 billion in 2020 due to which the EU member states fell short of their 2017 commitment to spend at least 35 percent of their equipment procurement budget with other member states.

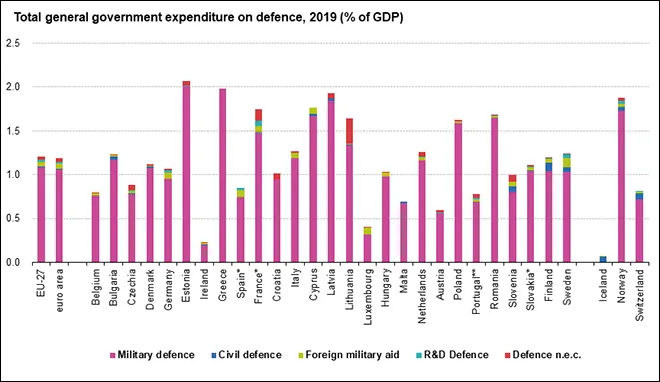

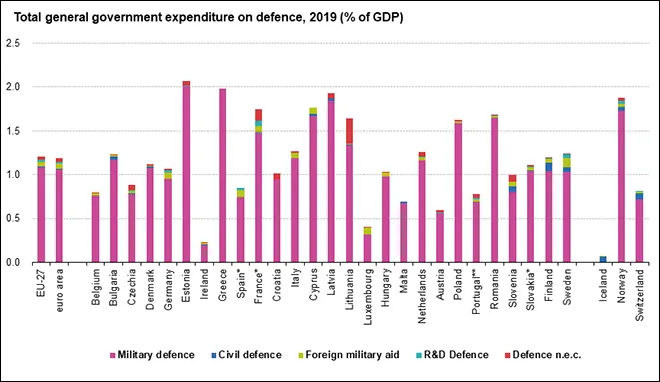

The French President, Emmanuel Macron, ever since coming to power in 2017 has advocated establishing a true European army and increasing Europe’s military spending. However, his appeal has found minimal resonance across the bloc with the majority of the member states finding comfort in aligning with Washington for its security purposes than creating a European army. Additionally, the collaborative military defence spending dropped from €5.5 billion in 2017 to €4.1 billion in 2020 due to which the EU member states fell short of their 2017 commitment to spend at least 35 percent of their equipment procurement budget with other member states. Similarly, Europe’s military expenditure has decreased from US $303 billion in 2008 to US $292 billion in 2020. Ambitious initiatives such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), the European Defence Action Plan, and establishing new defence funds to facilitate the financing of research and development of EU military capabilities have not necessarily progressed as the European Defence Agency (EDA) warned EU member states over the lack of spending on defence research and technology. The disunion between the EU and UK has further impaired a united European response towards Russia, and Brussels’ failure to bridge the widening differences over the years is finally cracking the bloc, courtesy of Russia’s aggressive movement across the Ukrainian border.

Figure 1: EU Member States’ Total General Government Expenditure on Defence, 2019 - % of GDP

Source: Eurostat

Source: Eurostat

After the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in 2021, the European policymakers pro-actively sponsored investing in European strategic autonomy to decrease its dependence on Washington and conjure consensus within Brussels to make its own autonomic decisions. The desire to endear European sovereignty by President Macron which was also highlighted as one of France’s major agendas in its Presidency of the EU is in its nascency, as the term necessitates a vivid understanding to the majority of the member states. After Brexit, France and Germany have become the two figureheads in the EU's governance and policymaking, therefore, both Paris and Berlin have been under immense pressure to cooperate with other member states and formulate a unison response towards Russia. However, circumventing this obstacle is a ginormous challenge by itself as various regions across Europe perceive Russia differently rather than being driven by a western narrative of the Kremlin. In Macron’s recent visit to Kremlin, he reiterated avoiding war and bridging the differences between Europe and Russia through diplomacy and trust-building measures. In the same meeting, Kremlin officials arranged for a 6-metre table where Putin and Macron sat at the ends of the table which metaphorically could also be decoded as apprehension and disjunction in relations between Russia and Europe. Germany’s new chancellor, Olaf Scholz also visited Moscow earlier this week in a last-ditch diplomatic attempt to reason with Putin. Scholz before visiting Moscow visited Washington, where multiple issues were discussed, notably Germany’s refusal to supply weapons to Kyiv, hesitancy in increasing Germany’s troop presence in Eastern Europe and the future of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. The pipeline for Washington has been an objectionable project since its conception as it would deliver gas from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea. The US has made its stance clear on the functionality of the pipeline since the beginning; however, in the context of the Russia–Ukraine issue, Washington has said that they will shut down the project.

After Brexit, France and Germany have become the two figureheads in the EU's governance and policymaking, therefore, both Paris and Berlin have been under immense pressure to cooperate with other member states and formulate a unison response towards Russia.

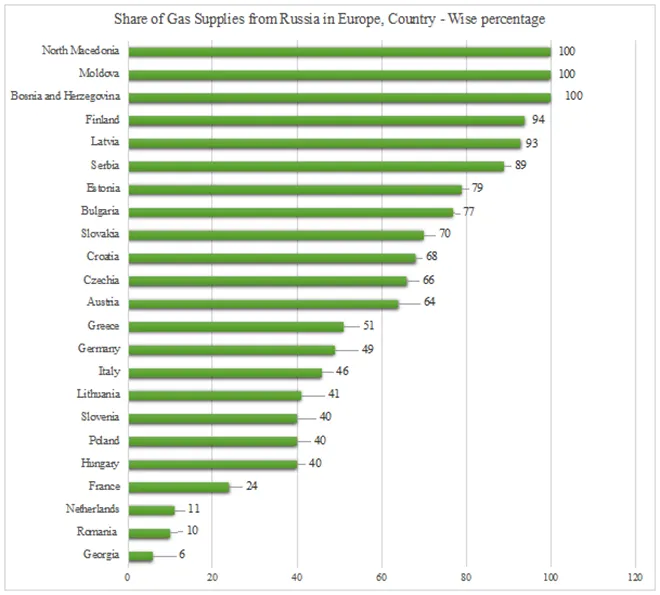

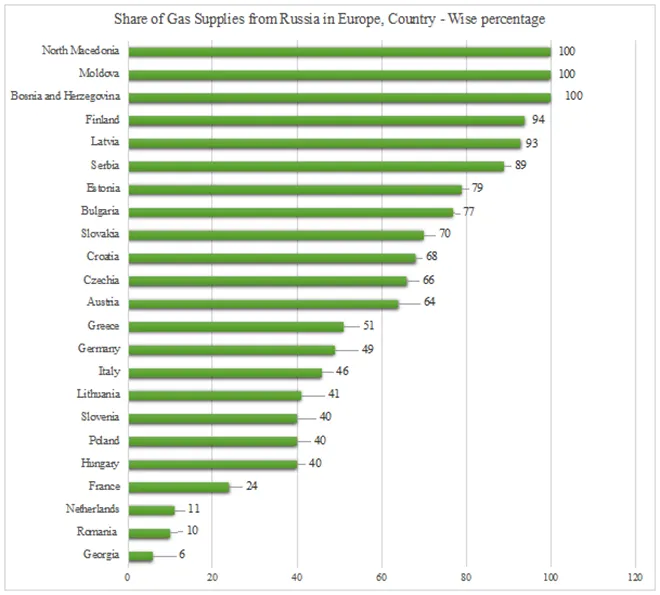

The defence ministers from NATO member states have met to strengthen their diplomatic strategy against Russia which is a major threat to European security since the Cold War. Fearing the fallout in Eastern European states, NATO troops have been deployed in Poland and the Baltic states to contain any Russian aggression. Furthermore, NATO is set to come up with four new battle groups in South-Eastern Europe as France has offered to lead the battlegroups in Romania. Europe and the West have threatened heavy sanctions on Russia if it invades Ukraine; however, Europe also faces a major energy security conundrum if it imposes sanctions on Russia. The EU imports 39 percent of its total gas imports and 30 percent of petroleum oil imports from Russia with CEE countries being almost 100 percent dependent on Russian gas. In absence of any signs of de-escalation from Russia, the EU has asked Qatar and Japan to provide LNG shipments as an alternative to Russian imports. However, this is a temporary resolution to a longer problem. The EU now attempts at diversifying its hydrocarbon imports by looking at Norway and Southern Europe can increase its imports via the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline. The EU is also aiming to incorporate nuclear energy into its energy architecture, however, nuclear availability is declining in Western European states due to phase-outs and other countries have raised objections against the inclusion of nuclear energy. Therefore, the EU is now looking at Africa for its energy imports and is eager to invest in joint EU–AU research on renewable energy, therefore, the EU aims to bolster Africa’s role in the EU’s hydrogen imports.

Figure 2: Share of Gas Supply from Russia to Europe (2020), Country Wise Analysis

Source: Data obtained from Eurostat and European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators; Graph by Author.

Source: Data obtained from Eurostat and European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators; Graph by Author.

The current situation in Europe is characterised by regional security affecting climate actions that can be detrimental not only to the carbon neutrality ambitions but also cause disruption to livelihood across the continent in short term. With a potential war at the footsteps, Europe’s security threat is at an all-time high since the Cold War. The majority of the Europeans perceive the conflict in Ukraine as a European crisis that can have detrimental effects on European governance. Poland is increasingly worried about Ukraine’s invasion primarily because it shares its border with Ukraine, and any war-like scenario would create a massive influx of migrants from Ukraine. In recent months, Poland has been embroiled in differences with Brussels over the primacy of rule of law and other issues which impede democratic functioning. Moreover, the migration crisis is a major concern for Poland and the EU, especially after dealing with illegal migrants at the Poland–Belarus border. The Baltic states are cautious fearing that Russia will cut its energy supply, thereby, causing economic distress in the region. France, which is set for Presidential elections in April is concerned with cyber-attacks and Kremlin’s interference in their election.

The majority of the Europeans perceive the conflict in Ukraine as a European crisis that can have detrimental effects on European governance.

The European Commission has proposed a new emergency macro-financial assistance (MFA) programme for Ukraine for €1.2 billion with €600 million ready to be dispatched immediately to maintain Ukraine’s macroeconomic stability; however, the package is yet to be approved by all member states. The Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen in her speech reaffirmed Brussels’ commitment towards Ukraine and has not shied away from Kremlin’s threats. The future of Europe situates itself on a slippery slope with the EU having a bystander effect in the Russia–Ukraine conflict. In a of seven months, Brussels has faced multiple geopolitical challenges particularly the Afghanistan crisis, the natural gas crisis, the influx of migrants at the Poland–Belarus border and now the Russian presence at the Ukrainian border. The aforementioned challenges now compel Brussels to investigate deeply into establishing European strategic sovereignty which would allow the bloc to be at the forefront of its geopolitical decisions against external threats. While seeking solutions for the future, Brussels could perhaps consider adopting Gestalt psychology whose adage states that, ‘the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Likewise, a collected, cohesive, and unified EU is more likely to achieve optimal outcomes against external threats rather than being divisive which not only threatens Europe but could also have significant geopolitical repercussions.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV