This is the 136th article in the series–The China Chronicles.

Under Xi's rule, the CCP was going to be tougher on minorities, a move that could backfire in global organisations and amongst countries that had strong bonds with them, especially in Central Asia. The Muslims of Xinjiang became the CCP's first target under Xi's dictatorship, and have been subjected to grave human rights violations and high-tech surveillance. With its contested history, Xinjiang traditionally enjoyed solid cultural bonds with Central Asia. Increased Chinese economic exploitation and marginalisation of the native Uyghur Muslims under Xi's rule further fuelled the region's centrifugal tendencies and separatism.

China built pipelines to get oil and gas back to China and flooded the region's markets with cheap finished goods. Beijing also helped the CAR's communist leadership via loans and investments under flexible conditions.

China and Central Asia

After the breakup of the former Soviet Union, Beijing regarded the Central Asian Republics (CARs) as vital for the security of Xinjiang. Xinjiang also became China’s gateway to the markets of Eurasia, Europe, and Russia. The rich hydrocarbon resources of the CARs “is a rich piece of cake given to today's Chinese people by Heaven,” according to Lt. Gen. Liu Yazhou. China intensified its efforts to revive the ancient Silk Route in the region by building pipelines, railway links, and roads. With Russia's help, China created the Shanghai Five in 1996 to solve the problem of undefined borders through confidence-building measures. In 2001, with the entry of Uzbekistan, the Shanghai Five evolved into the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). The SCO was China's first multilateral organisation and China leveraged it for its mercantile economy and for the security of volatile Xinjiang. China, through SCO, persuaded the CARs to ban Uyghur organisations and intensify surveillance on Uyghur activists in the region.

China built pipelines to get oil and gas back to China and flooded the region's markets with cheap finished goods. Beijing also helped the CAR's communist leadership via loans and investments under flexible conditions. In 1994, Kyrgyzstan borrowed US $7.4 million in credit and another US $14.7 million in 1998. In 2005, Uzbekistan received a US $600-million loan. In 2009, China not only signed a US$ 10-billion loan for an oil deal with Kazakhstan but also gave another US$ 10-billion loan to the SCO to help the struggling economies of the organisation. Similarly, in 2011, Beijing sanctioned a US $4.1-billion loan to Turkmenistan. China also gained control over the region's political elites and used corruption to create a social class to serve Beijing's imperialistic interests.

Xi’s strategy for Central Asia

Xi was aware of his goals within China and his revamped foreign policy accordingly. Before initiating such actions, Xi laid the groundwork for a wide range of foreign policy steps. He built Beijing-centric global institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and fortified China’s position in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

Xi used BRI for a multifaced strategy in an ambitious drive to make China a global player; to transit finished goods to different parts of the world; and to use its economic clout to Beijing's favour in BRI participant countries at international organisations.

In Central Asia, Beijing established a military base at the strategic Wakhan Corridor in Tajikistan. The region became the vital linchpin for China's “march west strategy”. In September 2013, Xi announced the launch of BRI in Kazakhstan as the “project of the century”. Xi used BRI for a multifaced strategy in an ambitious drive to make China a global player; to transit finished goods to different parts of the world; and to use its economic clout to Beijing's favour in BRI participant countries at international organisations. For the CARs, BRI was a chance to blur the physical barriers for continental connectivity projects and once again assume centrality in global trade.

As Xi’s control tightened in the Xinjiang region, a series of policies that violated human rights were undertaken and surveillance has been increased since 2014. The CCP constructed more than 1,200 detention centres to imprison more than one million Muslims, including Uyghurs, Kazaks, and Uzbeks. These Muslims were detained on the flimsy pretexts of wearing a veil or growing a long beard. Central Asia has a population of more than 300,000 Uyghurs. Xinjiang, on the other hand, had 1,810,507 Kazakhs, 196,320 Kyrgyz, and many Uzbeks with a sizeable Uyghur population within the region. The activists who raised their voices against the Chinese ill-treatment of these minorities were sent to jail or forced to leave the region. Xi used China's economic clout under BRI and its investments in the CAR to keep the rising dissatisfaction against Chinese treatment of their ethnic brethren under control. The Central Asian countries also detained many Uyghurs and Kazaks Muslims escaping from the atrocities and sent them back to China.

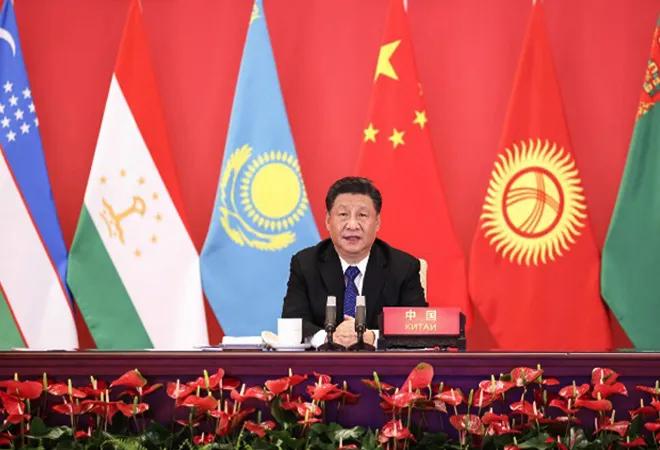

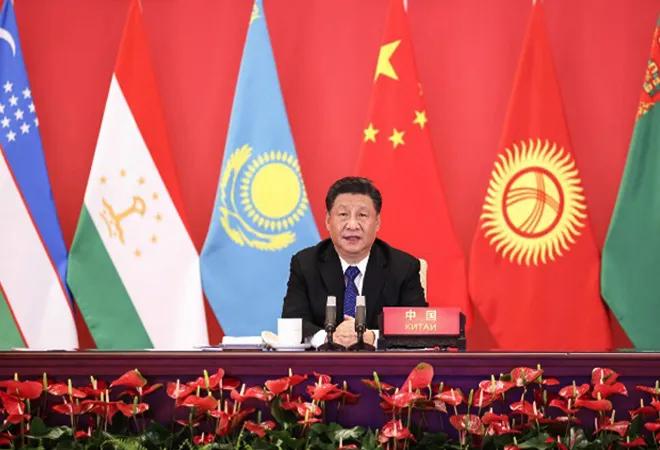

Globally, the CARs have helped Xi defend his policies in Xinjiang and other minority regions at global forums. In October this year, the United States-led core group of democracies presented a draft resolution to the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) to debate the human rights situation in Xinjiang. The 47-member council of the UNHRC rejected the US-led draft resolution. Only 17 members voted in favour of the draft resolution, and 19 voted against it. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, who had earlier abstained on the Uyghur issue at global forums and endorsed CCP's actions in Xinjiang, also voted against the draft resolution. The favour from these two larger Central Asian countries came after Xi visited both countries in September during the SCO summit. Xi, during his first foreign visit after COVID-19, signed a new US$ 4.1-billion railroad deal with Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Xi used China's economic clout under BRI and its investments in the CAR to keep the rising dissatisfaction against Chinese treatment of their ethnic brethren under control.

Xi also set aside Deng Xiaoping's cautious approach to China's foreign policy and abandoned his strategy of “hiding its capacities and biding its time”. On the contrary, Xi strived for global hegemony, with authoritarianism as a core value, which is being perceived negatively by the US and the West. This uncompromising attitude under Xi forced the Western democracies to adopt a policy of strategic pushback.

On 23 October, Xi secured a historic third term with a strengthened inner circle of loyalists. However, Xi’s third term will face an inevitable confrontation with the US and the West on trade, tech, and human rights in Xinjiang, Tibet, and frictions over Taiwan. This intensified rivalry between the US and China that the Biden administration calls a “decisive decade” is seen by Beijing as external attempts to blackmail, contain, and blockade. The Russia-Ukraine war adds supplementary concerns within the CARs on territorial integrity, trade, and transit routes via Russia. Some Central Asian countries have even criticised Russia and sent humanitarian aid to Ukraine. Under such challenging, confrontational geopolitical and geostrategic circumstances, the geographical centrality of Central Asia coupled with a receding Russia will help Xi to assert himself in the region more than ever.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV