Towards the end of her budget speech on Saturday, the Finance Minister made a puzzling announcement — new domestic companies engaged in electricity generation would be given a concessional corporate tax rate of 15%. Given what she’d said earlier about curbing pollution and shutting down old coal power plants, one would have expected this to be confined to renewable energy.

The answer lies in the

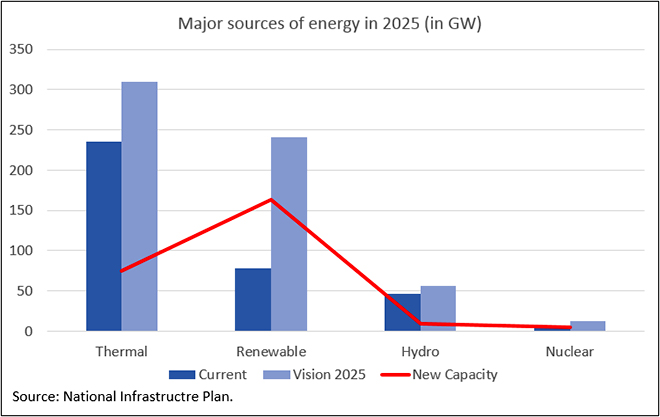

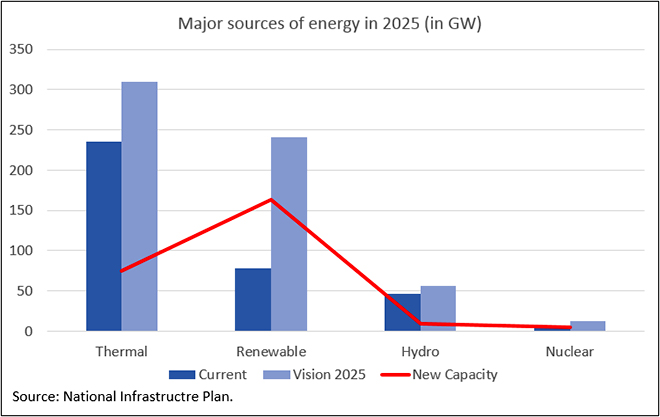

National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) put out by the Finance Ministry last month. While the government plans to bring the share of thermal energy in India’s energy mix down to 50% (from 66% currently), this still involves adding around 75 GW of thermal capacity in the next five years, and total thermal capacity of 310 GW. This number is far higher than the figures put out in the

National Electricity Plan 2018 (NEP 2018), which estimated thermal (coal and gas) capacity of 264 GW by 2026-27, at 43% of total capacity.

While the Finance Minister stated in her speech that the government would advise utilities to close down thermal plants which violate emissions regulations, there is no clarity on how this will be accomplished and what incentives will be provided to these companies. So far, the thermal power industry has

repeatedly flouted emissions norms, and deadlines for compliance have been extended multiple times.

The funding pattern in the NIP has the government financing around 90% of increased ‘conventional power’ capacity, which will cost around ₹12 trillion. While this does not differentiate between thermal and hydro-electric power, given the tiny increase in new hydro capacity, it seems likely that the money will be spent mostly on thermal plants.

The funding pattern in the NIP has the government financing around 90% of increased ‘conventional power’ capacity, which will cost around ₹12 trillion.

In contrast, the renewable energy capacity projected for 2025 in the NIP is 39% of the total mix, about 5% less than the projections in the NEP 2018. Surprisingly, the financing of new renewable energy capacity of 163 GW, at a cost of ₹9 trillion, has been left entirely to the private sector. While the report states there is a “well-stocked pipeline to FY25 because of 450 GW target visibility,” only 3% of projects are currently at the implementation stage.

A similar set of questions arise over the plan for farmers to use barren and fallow land to build solar power plants and sell it back to the grid, getting an additional source of income. This is to be done under the

Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) Scheme, which was announced in July last year. The implementation guidelines state that power plants of 500 kW to 2 MW capacity will be set up individual farmers or rural groups like cooperatives, panchayats etc. and the power generated by them will be purchased by local distribution companies (DISCOMs). The government is not providing any incentives/subsidies for the farmers building the solar plant, but will provide an incentive to the DISCOM buying the power.

The

estimated cost of a 1 MW solar plant is between ₹4–5 crore, and requires one hectare of land. For the average Indian farmer, this is more than 400 times their annual income

<1>, and would require their entire landholding.

<2> While there is a provision for leasing the land to developers who will then build the solar plant, the poor state of land records will make it difficult for small farmers to exercise this option. So far, there is no detail on how many solar plants have been commissioned since the inception of this scheme, but the cost appears prohibitive for all but the richest farmers.

This lopsided allocation of funds could easily lead to the government missing its target for renewable energy capacity, with huge costs to the environment. Under current trends,

CRISIL estimates that India will add only 40 GW of renewable energy by 2022, 42% short of the 175 GW target. This is largely due to policy uncertainty — state distribution companies delay payments to renewable energy generators, state governments cancel or try to renegotiate contracts if tariffs are too high, and low tariff caps make projects unviable. Therefore, despite the increase in tendering volume, the allocation of projects has slowed down — tenders are increasingly undersubscribed and cancellations of awarded tenders have increased. While lower tax rates are a welcome start, they should have been used to create an advantage for renewable energy companies. As things stand, they will not be sufficient to kickstart private sector investment if the policy environment remains unstable.

<1> NABARD All India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey (NAFIS) 2016-17

<2> Agriculture Census 2015-16

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Towards the end of her budget speech on Saturday, the Finance Minister made a puzzling announcement — new domestic companies engaged in electricity generation would be given a concessional corporate tax rate of 15%. Given what she’d said earlier about curbing pollution and shutting down old coal power plants, one would have expected this to be confined to renewable energy.

The answer lies in the

Towards the end of her budget speech on Saturday, the Finance Minister made a puzzling announcement — new domestic companies engaged in electricity generation would be given a concessional corporate tax rate of 15%. Given what she’d said earlier about curbing pollution and shutting down old coal power plants, one would have expected this to be confined to renewable energy.

The answer lies in the  While the Finance Minister stated in her speech that the government would advise utilities to close down thermal plants which violate emissions regulations, there is no clarity on how this will be accomplished and what incentives will be provided to these companies. So far, the thermal power industry has

While the Finance Minister stated in her speech that the government would advise utilities to close down thermal plants which violate emissions regulations, there is no clarity on how this will be accomplished and what incentives will be provided to these companies. So far, the thermal power industry has  PREV

PREV