When India’s first full–length feature film —

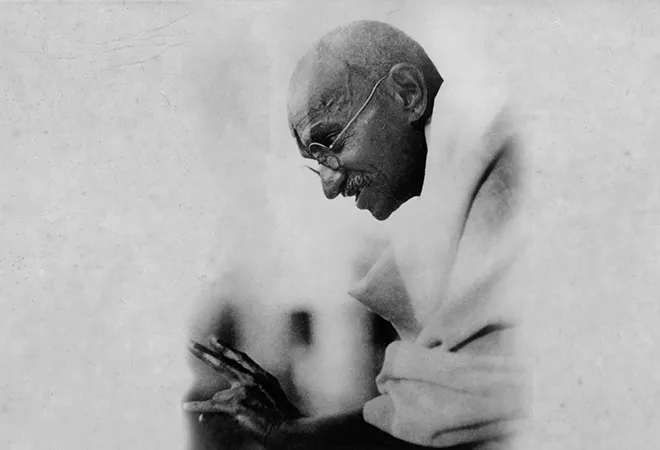

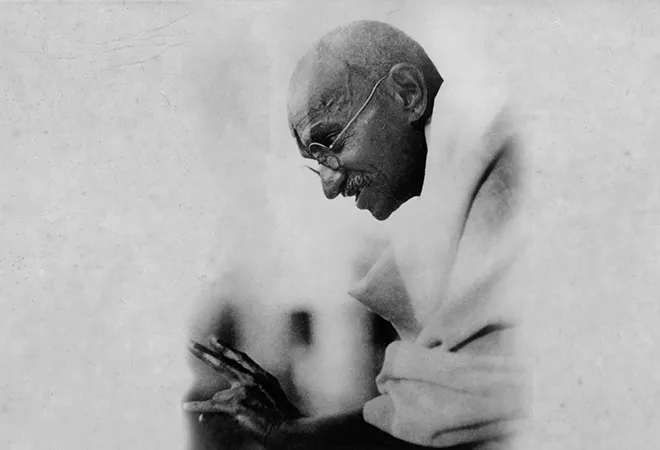

Raja Harishchandra was released, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was 7,045 km away from his homeland, carrying out his last political campaign in Durban, South Africa. The lawyer from Porbandar was now contemplating his return to India.

For decades to come, Gandhi’s influence on Hindi Cinema remained etched. Dadasaheb Phalke, V. Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor to more recently — Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Aamir Khan to Rajkumar Hirani — dozens of film makers consciously worked on Gandhian principles and teachings into their celluloid ventures. Gandhi remained highly sceptical of the moral impact of cinema on the masses.

It is ironical that the man who could not sit through

Ram Rajya — the only film he was made to watch on 2 June 1944 at Juhu, Bombay — would turn out to be a source of inspiration for an entire galaxy of filmmakers, Dadasaheb Phalke among them, known for their meaningful cinema.

In 1927, a questionnaire was sent to Gandhi by the Indian Cinematograph Committee. A Bombay daily sought Gandhi’s message on the occasion of the 25th year of Indian cinema. Mahadev Desai who was serving as Gandhi’s secretary, responded that Gandhi had least interest in cinema and a word of appreciation should not be expected.

The Mahatma’s impact was evident in the works of Phalke, Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor, Hirani etc. The films dealt with the core themes of Gandhian ideology — non–violence, love and sacrifice, Hindu–Muslim unity, the rural–urban divide, rejection of crass commercialism, women’s emancipation and fear of moral decay.

The Mahatma’s impact was evident in the works of Phalke, Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor, Hirani etc. The films dealt with the core themes of Gandhian ideology — non–violence, love and sacrifice, Hindu–Muslim unity, the rural–urban divide, rejection of crass commercialism, women’s emancipation and fear of moral decay. It was through their movies that Gandhi emerged as a towering moral force. While these filmmakers may not have imbibed his ideas consciously, their films revealed his influence, all the same, and it became a guarantee for success. Gandhism was, after all, too dominant an idea for idealistic filmmakers not to be swayed by it.

In the decade that followed the release of the first Indian film (1913–1922), over ninety films were produced in the country. Most of them were based on Indian mythology — an enduring theme that was also used quite liberally by Gandhi in his political and social discourses. In those days, cinema halls did not exist. Films would be screened in the open after sunset, with a tent covering the space where the ‘show’ was held. This arrangement called for considerable courage on the part of rural folk to watch films, as it required them to venture out after dark and return home late at night on foot, in the absence of transport, with no street lights to guide them on their way.

Film historian, distributor, producer and writer Jaiprakash Chouksey claims that during the first phase of Indian cinema, the masses, especially from the working class, were emboldened to conquer their fear of the dark, primarily by Gandhi’s urge, and come out in droves to watch mythological movies in rundown but burgeoning cinema halls across the country. He also insists that the Mahatma’s emphasis on religion and mythology in his political agitation against the British helped generate a great deal of interest in the films of that era. Gandhi’s political meetings would begin with multi–faith prayers, a practice that encouraged participants to respect religion and plurality — something the filmmakers of the time leveraged to the hilt.

In the decade that followed the release of the first Indian film (1913–1922), over ninety films were produced in the country. Most of them were based on Indian mythology — an enduring theme that was also used quite liberally by Gandhi in his political and social discourses.

Filmmaker Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and several others tried their best to convince him otherwise and argued that cinema was a force to contend with and could be used to advantage in disseminating his ideas, a doubting Gandhi preferred to rely on the efficacy of print media for the purpose.

After cinema found its voice, Mahatma Gandhi’s message became bolder and easier to interpret in Hindi Cinema. The release on 14 March 1931 of the first Indian talkie, Ardeshir Irani’s

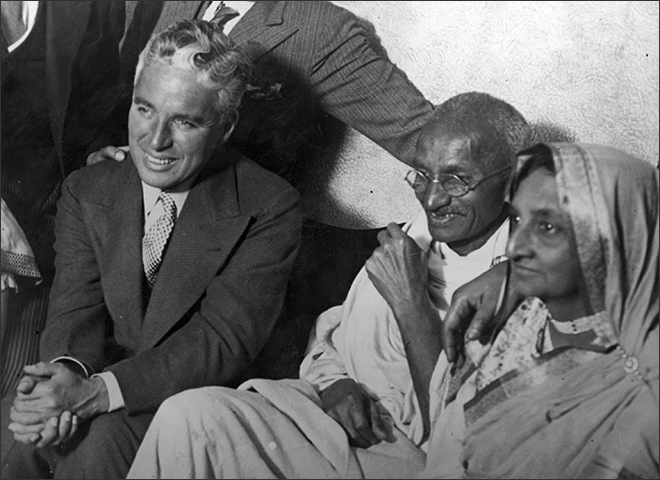

Alam Ara, would be followed, not long afterwards, by a serendipitous meeting in London between Charlie Chaplin and Gandhi in September 1931. Five years later, in 1936, Chaplin produced what was to eventually become a cult classic:

Modern Times. Depicting the dehumanising effects of the machine that was increasingly replacing manual labour, the film endorsed, in a way, Gandhi’s opposition to rampant mechanisation.

Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Katral — Canning Town, east London, 1931. © London Express/Getty Images

Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Katral — Canning Town, east London, 1931. © London Express/Getty Images

The Gandhi–Chaplin meeting provides an interesting anecdote for Indian history. According to a programme on BBC Radio 4, ‘Making History: Gandhi and Chaplin’, the Mahatma was in London to attend the Second Round Table Conference and had refused to stay in a West End hotel,

instead choosing to be with people from the working class at Kingsley Hall in East London. The Kingsley Hall Community Centre in Bow was run by Muriel Lester, a Christian pacifist who had visited Gandhi’s ashram in India in 1925. She shared his political beliefs and his idealism.

In her book

Entertaining Gandhi, published in 1932, Lester tells the story of the Mahatma’s visit and his meeting with Chaplin. “One of my clearest mental pictures,” she writes, “is of Mr. Gandhi sitting with a telegram in his hand looking distinctly puzzled. Grouped round him were secretaries awaiting his answer. As I came in, the silence was being broken by a disapproving voice saying, ‘but he’s only a buffoon, there is no point in going to meet him.’ The telegram was being handed over for the necessary refusal when I saw the name. ‘But don’t you know that name, Bapu?’ I inquired, immensely intrigued. ‘No,’ he answered, taking back the flimsy form and looking at me for the enlightenment that his secretaries could not give. ‘Charlie Chaplin! He’s the world’s hero. You simply must meet him. His art is rooted in the life of working people, he understands the poor as well as you do, he honours them always in his pictures.’ So, on 22 September 1931, at Dr. Katial’s house in Beckton Road, Canning Town, the local people were given the double thrill of welcoming both men.”

The process of economic liberalisation in the early 1990s introduced certain hedonistic changes in the cinematic preferences of the masses. The Mahatma’s ideal of simple living and high thinking was no longer as abiding an inspiration for the cinema–going public as it had once been.

The Gandhian imprint was also apparent in Hindi films based on women’s emancipation, marking a significant departure from the way the growing industry had progressed till then. Shantaram’s

Amar Jyoti (1936), for instance, dealt with the heroine’s revolt against her alcoholic husband, marking a trend in a period during which a large number of women had cast off the yoke of social restrictions to take part in the freedom movement. Though it was a period film, the heroine’s resistance to extreme ‘patriarchal laws’ was the central plot of the film.

The process of economic liberalisation in the early 1990s introduced certain hedonistic changes in the cinematic preferences of the masses. The Mahatma’s ideal of simple living and high thinking was no longer as abiding an inspiration for the cinema–going public as it had once been. Declining interest was increasingly evident in the low viewership for films on Gandhi. While an earlier film on the Mahatma, Sir Richard Attenborough’s

Gandhi (1982), had turned out to be one of the most successful international films ever made, the times were changing. Fourteen years later,

The Making of the Mahatma (1996) by Shyam Benegal turned out to be a commercial failure. Kamal Haasan’s

Hey Ram (2000), with Naseeruddin Shah in the role of Gandhi, also proved to be a flop. Gandhi, however, would be reinvented and his image resurrected by Rajkumar Hirani. With his film

Lage Raho Munna Bhai (2006), the director gave an irresistible contemporary twist to the Mahatma’s message that caught the imagination of the masses.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

When India’s first full–length feature film — Raja Harishchandra was released, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was 7,045 km away from his homeland, carrying out his last political campaign in Durban, South Africa. The lawyer from Porbandar was now contemplating his return to India.

For decades to come, Gandhi’s influence on Hindi Cinema remained etched. Dadasaheb Phalke, V. Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor to more recently — Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Aamir Khan to Rajkumar Hirani — dozens of film makers consciously worked on Gandhian principles and teachings into their celluloid ventures. Gandhi remained highly sceptical of the moral impact of cinema on the masses.

It is ironical that the man who could not sit through Ram Rajya — the only film he was made to watch on 2 June 1944 at Juhu, Bombay — would turn out to be a source of inspiration for an entire galaxy of filmmakers, Dadasaheb Phalke among them, known for their meaningful cinema.

In 1927, a questionnaire was sent to Gandhi by the Indian Cinematograph Committee. A Bombay daily sought Gandhi’s message on the occasion of the 25th year of Indian cinema. Mahadev Desai who was serving as Gandhi’s secretary, responded that Gandhi had least interest in cinema and a word of appreciation should not be expected.

When India’s first full–length feature film — Raja Harishchandra was released, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was 7,045 km away from his homeland, carrying out his last political campaign in Durban, South Africa. The lawyer from Porbandar was now contemplating his return to India.

For decades to come, Gandhi’s influence on Hindi Cinema remained etched. Dadasaheb Phalke, V. Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, Raj Kapoor to more recently — Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Aamir Khan to Rajkumar Hirani — dozens of film makers consciously worked on Gandhian principles and teachings into their celluloid ventures. Gandhi remained highly sceptical of the moral impact of cinema on the masses.

It is ironical that the man who could not sit through Ram Rajya — the only film he was made to watch on 2 June 1944 at Juhu, Bombay — would turn out to be a source of inspiration for an entire galaxy of filmmakers, Dadasaheb Phalke among them, known for their meaningful cinema.

In 1927, a questionnaire was sent to Gandhi by the Indian Cinematograph Committee. A Bombay daily sought Gandhi’s message on the occasion of the 25th year of Indian cinema. Mahadev Desai who was serving as Gandhi’s secretary, responded that Gandhi had least interest in cinema and a word of appreciation should not be expected.

Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Katral — Canning Town, east London, 1931. © London Express/Getty Images

Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Katral — Canning Town, east London, 1931. © London Express/Getty Images PREV

PREV