The fourth tranche of the stimulus package announced measures that gave a boost to the coal industry in India. A Rs 50,000 crore package was announced for the evacuation of the mined fuel. The distinction between captive and non-captive mines was done away with, which means that there are no end-use restrictions now for private firms. India hopes that with the participation of the private sector, India will become self-sufficient in coal production and will be able to reduce its dependence on imports. In 2018, the private sector was allowed to sell up to 25% of their output in the market, the first step towards commercialisation. However, private sector remains cautious about investment in this sector, given the COVID pandemic. The coal auctions have been postponed to October for now but there are larger roadblocks that question how private sector would be able to successfully invest in coal projects and the consequences for the financial sector.

In India, the reasons for build-up of stranded assets or underutilisation of coal projects are due to non-availability of land, lack of a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), lack of availability of coal, etc.

India currently has about 62 GW of coal projects under construction. Public sector institutions and banks are major financiers of coal projects. In 2018, the standing committee report shows that about 65,000 MW operational coal-based power plants in the private sector selected for the study, are under financial stress, which stands at more than 85%. This has already impacted the financial sector. It translated to an equivalent exposure of about Rs 3 lakh crores for lenders, which are primarily scheduled banks, and thus adds to the non-performing assets (NPA) problem in the banking sector. Majority of the NPAs in the banking sector is concentrated in a few sectors, one of which is the power sector.

In India, the reasons for build-up of stranded assets or underutilisation of coal projects are due to non-availability of land, lack of a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), lack of availability of coal, etc. But, in addition, the coal sector as a whole faces the problem of stranded asset on account of competition from renewable and policies changing globally away from coal-fired projects. This trend is reflected in India as well.

It is important that the future build-up of stressed assets is prevented.

Stranded coal assets have implications for the economy. High NPA in the banking sector reflects the state of the economy. It affects liquidity in the economy and increases the risk of default. It also diverts funds away from renewable energy. The government and RBI have taken steps to address the issue of NPA and stressed assets in the banking sector. Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code is a step towards resolving the issue of stressed assets in the coal sector. In the future, India is likely to face a stranded asset problem of about US$ 40 billion. Hence, it is important that the future build-up of stressed assets is prevented.

Source of finance: Current trend

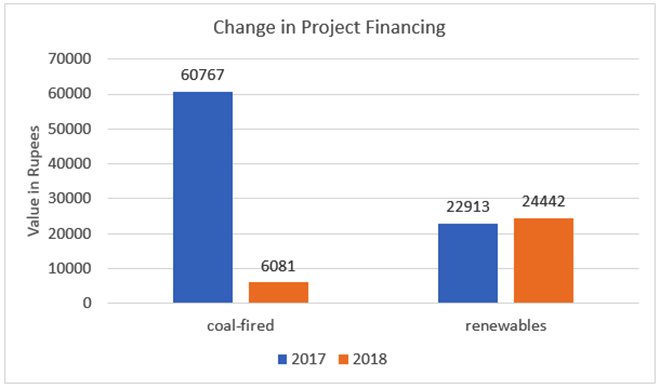

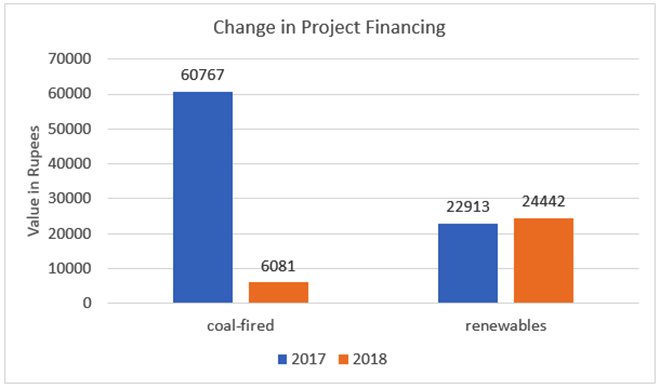

In India, the financing of coal-fired plants reduced by 90 percent in 2017 and 2018. The number of such projects also came down from 12 to 5 in 2018. More than 80% of loans went to the renewable sector in 2018, out of all the projects that achieved financial closure. The graph below shows that the primary source of funding has also declined by 90% for coal projects whereas for renewables they have increased by 10%. Also, the incremental capacity additions of renewable power is double that of coal. For the third consecutive year, the additions under renewable power was more than that under conventional powers such as coal.

Data from Centre for Financial Accountability (CFA) report

Data from Centre for Financial Accountability (CFA) report

International finance for coal projects is also drying up. Even countries such as Japan, China and Korea are facing pressure to stop funding of coal projects in Asia. Given the present trend, newer plants will find it difficult to achieve financial closure. This is likely to intensify the issue of stranded assets and financial stress of banks and financial institutions. Further, it is the public sector that will be expected to foot the bill for newer power plants as the private sector may have few takers.

There is a need for better data, to analyse climate-related risks the financial institutions and corporates face.

The Group of 20 finance ministers, this year, included a statement about the financial stability implications of climate change. Even the US admitted that climate change has serious economic implications. Christine Lagarde, recently at the launch of the financial agenda of UN’s COP26 climate summit, spoke about the importance of financial institutions to be transparent about the climate risks they face. There is a need for better data, to analyse climate-related risks the financial institutions and corporates face. Regulators around the world have already started taking steps. Central banks in Brazil, China and recently South Africa have incorporated policy measures to factor in environmental factors.

Greater access to energy is a key policy objective for India, therefore coal will continue to get policy support, but ― it is no longer possible to ignore the economic consequences of climate changes and any delay is not feasible. However, India would have to gradually phase out coal investments and devise a roadmap on how to deal with stranded assets. Alongside, India must take similar steps to protect the economic health of banks and financial institutions through.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Data from Centre for Financial Accountability (

Data from Centre for Financial Accountability ( PREV

PREV