This article is part of the new publication — Reconciling India’s Climate and Industrial Targets: A Policy Roadmap.

This article is part of the new publication — Reconciling India’s Climate and Industrial Targets: A Policy Roadmap.

Introduction

India’s climate policies have consistently aimed at fostering green growth in the country, with the development of green industries being a focus area. However, despite concerted efforts and huge growth potential, India’s ‘green market’ remains at a nascent stage. While the growth of green industries requires policies that stimulate both demand and supply to achieve market growth,<1> Indian policies have only managed to successfully increase production capacities for green products without a similar boost in demand.

Indeed, green industries in India find it difficult to capture the market owing to consumer perceptions and preferences.<2>,<3>,<4> Consumers tend to purchase goods that are produced using more pollutive processes even as they are willing to switch to sustainable products; there are various reasons: they are restricted by the large costs of environmentally sustainable products; there is a lack of an enabling environment to create better access to green products; an overall dearth of information about available green products and their benefits; and a lack of confidence regarding what is termed ‘green’ by companies.<5>

A shift in consumer perceptions and preferences towards green products can be achieved by addressing the issues on the demand side.

Several studies show that a change in consumption behaviour patterns towards environmentally sustainable goods and products can lead to a larger market share for them.<6>,<7> A shift in consumer perceptions and preferences towards green products can be achieved by addressing the issues on the demand side. Thus, it is paramount for a green industrial policy to incorporate market creation strategies aimed at increasing market demand for, and access to green sectors over traditionally polluting sectors. This chapter studies the biggest sources of industrial emissions and recommends policy instruments aimed at demand-creation for greener sources.

Scope of the study

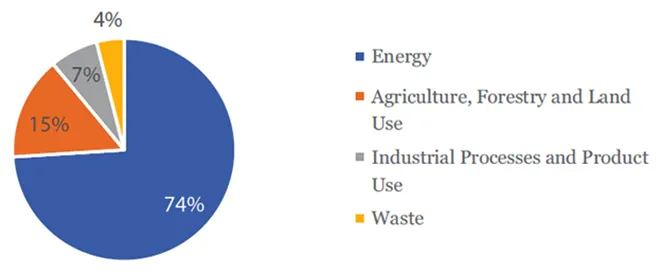

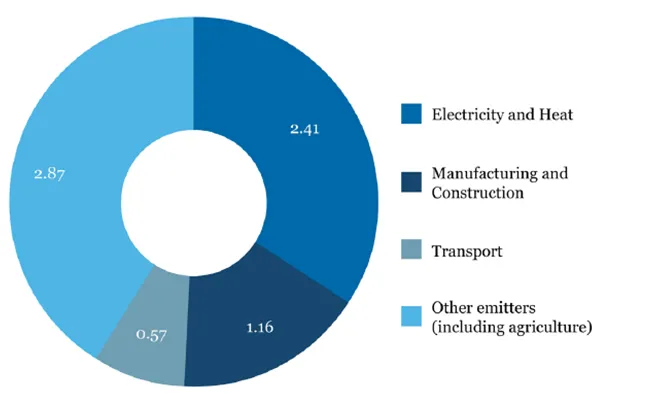

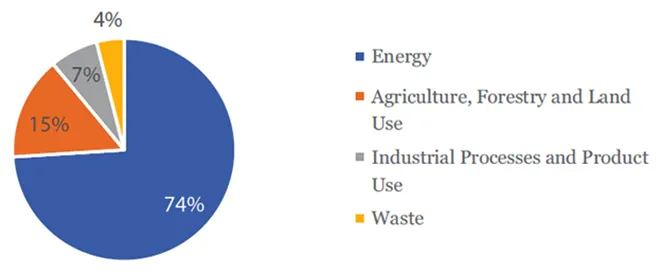

Emissions from India constitute seven percent of the total global emissions.<8> According to GHG Platform India, the energy sector and industrial process and product use (barring Agriculture) are the highest emitters in India (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Emissions from India, by Sector

Source: GHG Platform India<9>

Source: GHG Platform India<9>

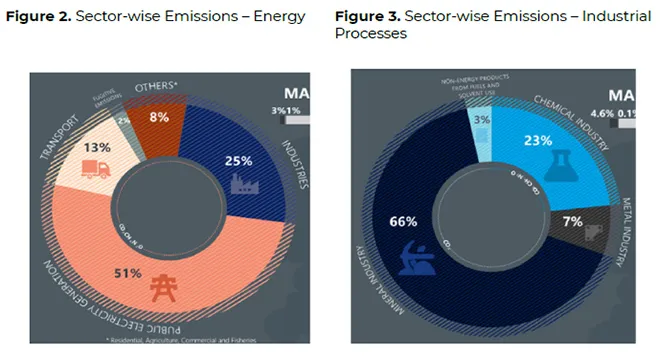

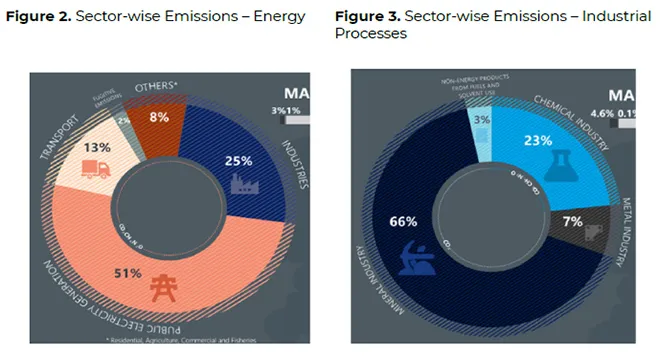

Industry in India drives emissions emerging from these two sectors. Within the energy sector (See Figures 2 and 4), the three biggest emitters are electricity and heat generation, industries (comprising manufacturing and construction), and transportation. Within the industrial processes sector (See Figures 3 and 5), the mineral industry (comprising iron and steel, and cement) is the biggest emitter. Since the manufacturing and construction industry is the sole contributor of industrial emissions, and industry is a big consumer of electricity and heat generation, as well as road transport, the emissions from these sectors are largely driven by industries. Overall, industrial emissions are responsible for a quarter of the emissions in India.

Source: GHG Platform India<10>

Source: GHG Platform India<10>

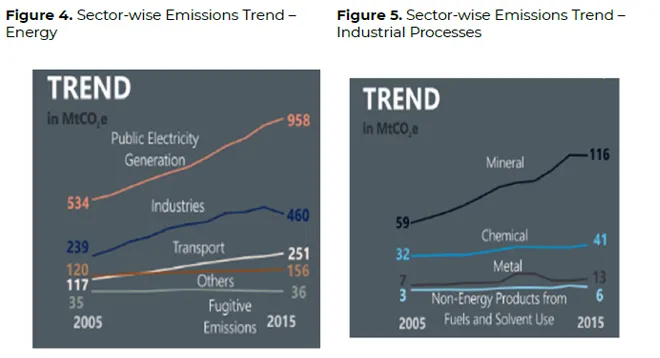

To understand the magnitude of the emissions from these sectors from India, one must note that Electricity and Heat constitute 2.41 percent of the seven percent global emissions from India; Manufacturing and Construction constitute 1.16 percent; and Transportation constitute 0.57 percent (See Figure 6).

Figure 6. India’s Contribution (7 Percent) to Global Emissions, by Sector

Source: Climate Watch<11>

Source: Climate Watch<11>

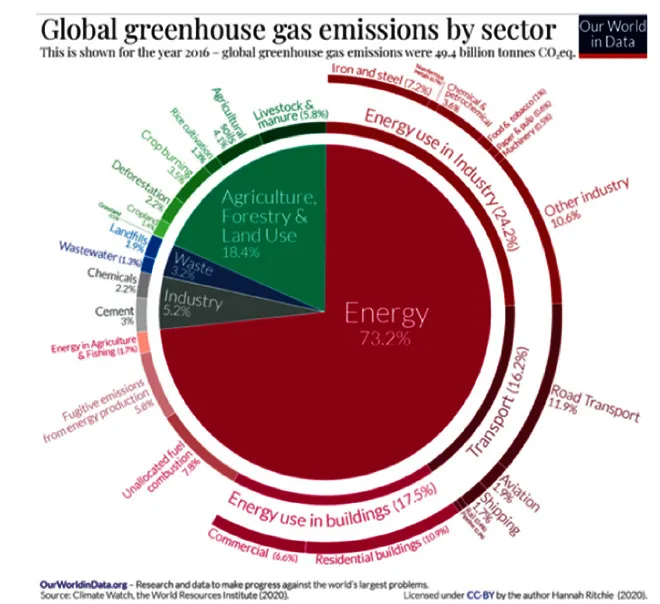

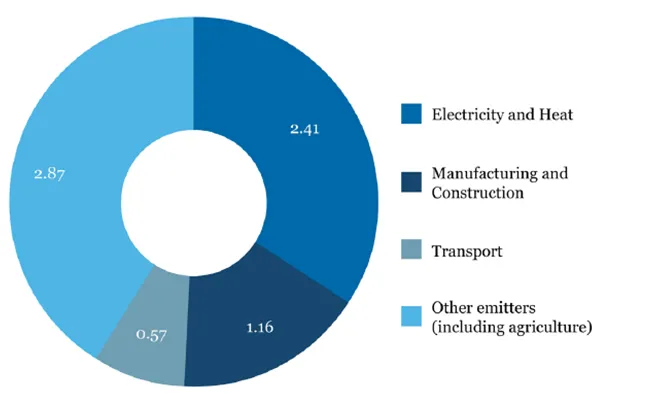

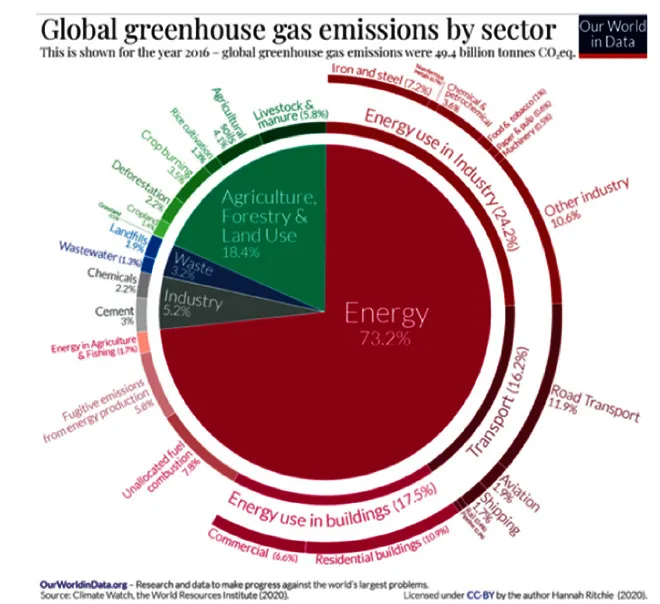

The breakup of sector-wise emissions from India matches global patterns (See Figure 7); thus, addressing emissions from these sectors is important for the world at large. While the energy sector contributes the most to global GHG emissions, within energy use, the highest emitters (as was the case in India) are industry (iron and steel being the largest), transport (especially road transport), and electrification and heating (specifically for buildings). Similarly, industrial process (particularly cement production) is the third-largest global emitter.

Figure 7. Global Greenhouse Emissions, by Sector

Source: Our World in Data<12>

Source: Our World in Data<12>

Polluting sectors: An overview

This section provides a brief overview of the three sectors, highlighting the source of pollution in each along with sustainable alternatives; the efforts undertaken by the government; the current gaps; and how the growth potential of these sectors requires the emissions to be addressed in an urgent manner.

Electrification and heat generation

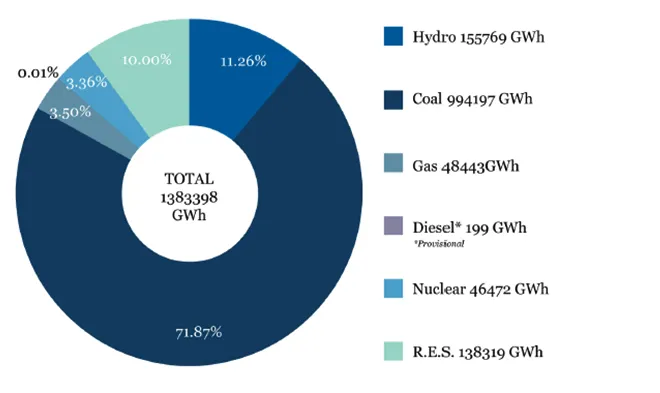

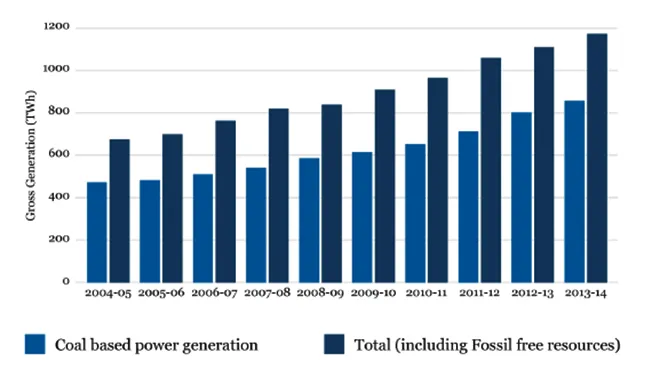

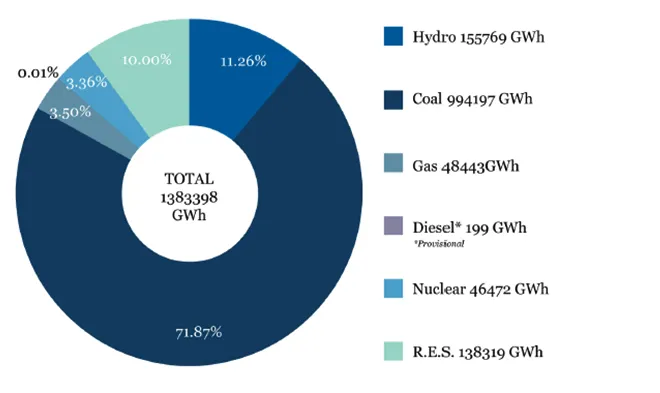

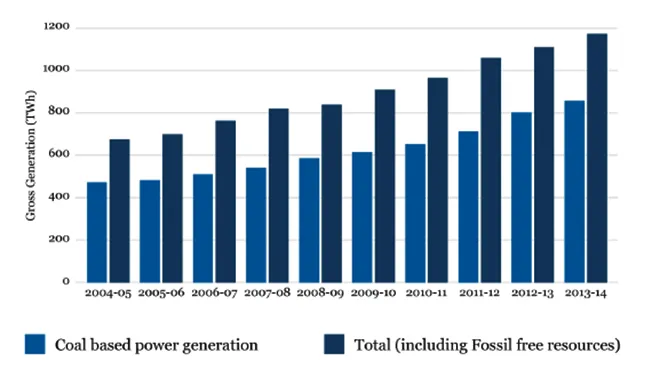

India ranks, respectively, third and fourth globally in terms of electricity production and consumption.<13> Fossil fuels — and coal in particular — dominate electricity and heat generation in India. In 2018-19, coal was used to generate over 70 percent of the country’s electricity, followed by renewable energy (RE) sources (See Figure 8). Indeed, the share of coal in India’s electricity generation has been on the rise in recent years (See Figure 9).

Figure 8. Gross Electricity Generation in India, Mode-wise (2019-20)

Source: Govt<14>

Source: Govt<14>

Figure 9. Share of Coal-based Power Generation (2004-05 to 2013-14)

Source: Shakti Foundation<15>

Source: Shakti Foundation<15>

The dominance of coal has made electrification highly polluting, with emissions from fossil fuels contributing to 96 percent of total emissions from the electricity generation sector. Since industries are the largest electricity consumers, comprising 44.11 percent of the total electricity consumption in the country, industry reports massive Scope 2 emissions that need urgent attention.<16>

During the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s proportion of RE rose from 17 percent to 24 percent, while coal-fired power declined from 76 percent to 66 percent.

To de-carbonise the electricity generation sector, the Government of India has made a push towards increasing the renewable generation capacity in the country, which is in line with its commitments to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Aiming to improve the affordability of solar and wind power, India introduced the National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency, focusing on the industrial and commercial sector.<17> In light of the increased emphasis on deploying RE sources, India’s expenditure on solar energy surpassed its spending on coal-fired power generation for the first time ever in 20190-20. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s proportion of RE rose from 17 percent to 24 percent, while coal-fired power declined from 76 percent to 66 percent. Consequently, the number of people working in RE in India has increased fivefold since 2015.<18>

Based on India’s current policies and its aim to reach 100-percent electrification to meet India’s SDG Targets, the country’s electricity demand could triple by 2040, due to increased appliance ownership and cooling needs.<19> This steady rise in the demand for electrification presents an opportunity for RE to overtake coal as the main source of electricity generation — that is, provided that market access and demand for RE is boosted. While a commitment to sustainability has led many companies to pledge to use 100 percent renewable-powered electricity, lack of access to certified, commercially supplied RE at a low cost remains a barrier.<20> Moreover, the general market for RE remains largely uneven, which creates an additional obstacle for demand. The NITI Aayog has observed that consumers of electricity are restrained by higher costs in states with poor RE source, whereas DISCOMs are hindered by the lack of demand in states rich in RE sources.<21>

Thus, phasing out coal and replacing it with RE via increased accessibility and affordability is crucial to reducing the emissions emerging from electrification. A greater emphasis on facilitating access to RE will also be key in attracting global RE100 companies.

Construction and manufacturing

The manufacturing and construction industries together account for 18.4 percent of the total emissions from the energy sector. Within this, the biggest polluters are cement, and iron and steel.<22>

Cement: India is the world’s second-largest cement producer, accounting for over eight percent of global installed capacity. In 2010, the cement industry’s share of India’s total CO2 emission was around seven percent. The construction industry’s demand for cement drives production and is thus a crucial contributor to total CO2 emissions. The construction of housing and real estate, followed by infrastructure (e.g. the development of roads) and industrial development are the largest consumers of cement.<23>

With India recognising cement production as a significant source of unsustainable production practices, there have been concerted efforts by the country’s private sector to embrace green practices.<24> Consequently, India’s CO2 emission in the cement sector has come down to 670-700 kg per tonne of cement, compared to the global average of 900 kg per tonne of cement.<25> However, while CO2 emissions from cement has been on a steady decline, it still makes up five percent of India’s total emissions.<26> This is largely due to the unaffordability of the green production practices for small- and medium-scale companies.<27>

With increased emphasis on infrastructure (NIP), housing (PMAY), real estate (smart cities) and industrial development (Make in India) by several Indian policies, cement production in India is expected to be 800 million tonnes by 2030.<28> Given the anticipated spike in the demand for cement, studies show that significant efforts will be needed to meet the 2050 objective of a 40-percent reduction in CO2-based emissions from cement production.<29>

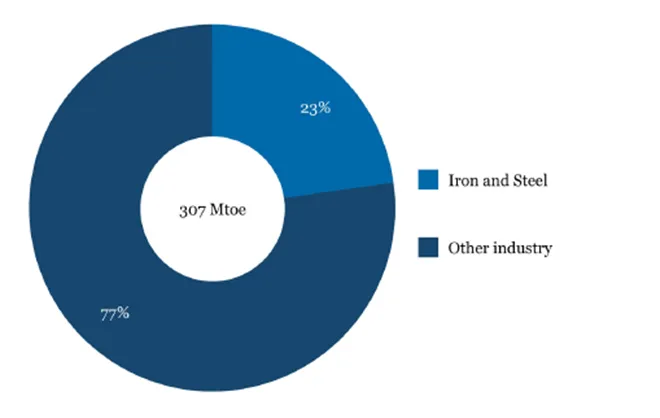

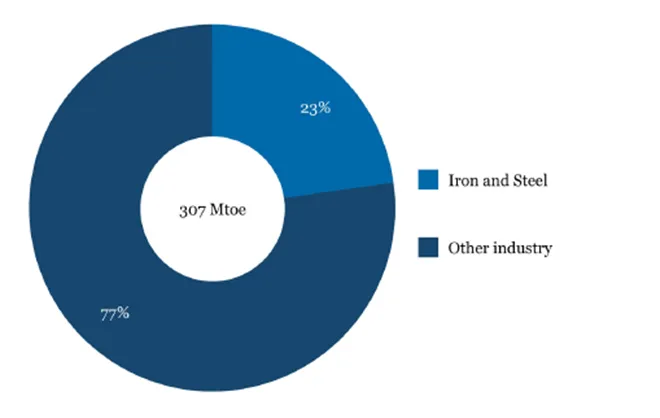

Iron and steel: India is the fourth-largest producer of crude steel in the world. The sector contributes around three percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), employing around 2.5 million people.<30> It also adds 6.2 percent to the national GHG load.<31> Within industry, the iron and steel sector is the largest energy-consuming sub-sector, accounting for over 20 percent of industrial energy use (See Figure 10).

Figure 10: Iron and Steel’s Share of Industrial Energy Use 2018-19

Source: TERI report<32>

Source: TERI report<32>

While critical for economic growth, the iron and steel sector is both energy- and resource-intensive, and the rapid growth of Indian steel demand has had significant environmental and economic consequences. The iron and steel sector accounts for 28.4 percent of the entire industry sector emissions, which constitute 23.9 percent of the country’s total emissions.<33>

There is enormous potential for growth in the consumption of iron and steel, due to the thriving automobile and railways sectors, infrastructure development, and construction.

To drive a reduction in energy use in the steel sector, one of the major initiatives undertaken by the Government of India is the Perform Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme.<34> Despite this, the average energy efficiency level of the industry remains low compared to global peers, and emissions from the sector are still significant and rising. The National Steel Policy, 2017 envisages 300 million tonnes of production capacity by 2030-31.<35> There is enormous potential for growth in the consumption of iron and steel, due to the thriving automobile and railways sectors, infrastructure development, and construction. In light of the present policies and the increased demand for iron and steel, experts estimate that emissions from the sector will increase to 837 MtCO2 per annum by 2050, i.e. nearly half of India’s total CO2 emissions in 2018.<36> This massive yet anticipated demand in manufacturing and construction creates an excellent opportunity for India to reduce emissions by increasing access to affordable low-carbon options for consumers.

Transportation sector

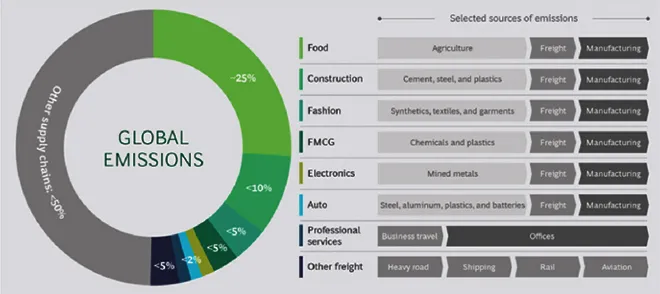

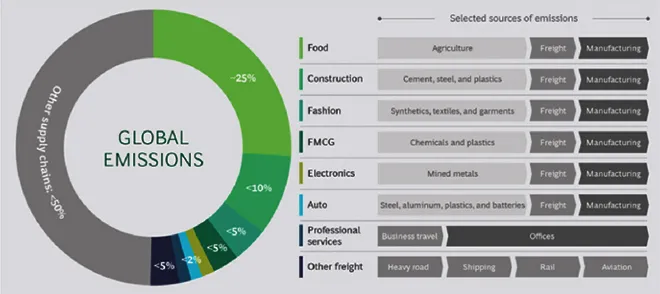

The transportation industry, including both passenger and freight, is vital for growth. The production of any commodity or service requires the transport of people and goods. Freight transportation, in particular, is a source of significant supply-chain emissions from all industries globally (See Figure 11).

Figure 11: Supply Chains that Dominate Emissions – Freight’s Contribution

Source: BCG analysis<37>

Source: BCG analysis<37>

In India, road transport is a dominant form of transportation, carrying almost 90 percent of the country’s passenger traffic and 65 percent of its freight — contributing 5.4 percent of India’s GDP.<38> Consequently, within the transport sector, road transport utilises 78 percent of the total energy share and contributes 87 percent of the total CO2 equivalent emissions. The two major fuels used by the transport sector are gasoline and diesel, both of which are highly carbon intensive and release greenhouse gases and other pollutants on combustion.<39>

India’s road transport has witnessed remarkable growth in recent years and is expected to grow at a significant rate in future. Current projections indicate that road transport traffic will grow more than five times from 2011-12 to 2031-32.<40> This growth will have a significant impact on the overall GHG emissions of the country. Recognising the need to decouple the growth of the transport sector from rising GHG emissions, the Government of India has already undertaken several initiatives to promote a sustainable mode of transportation. The National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), launched in 2008, includes “sustainable transport” under the National Mission on Sustainable Habitat. The Indian government is focusing on decarbonising the transport sector through increased efficiency, cleaner fuels (promoting the use of Liquefied Natural Gas and Compressed Natural Gas ), electric mobility (Electronic Vehicles ), creating an enabling environment, and modal shift.<41>

Unless the demand for cleaner fuels and EVs is boosted, increases in transport will continue to have serious health and environmental impacts.

Despite these efforts, the projected increase in road transport will lead to increased consumption of fossil fuels. Unless the demand for cleaner fuels and EVs is boosted, increases in transport will continue to have serious health and environmental impacts.

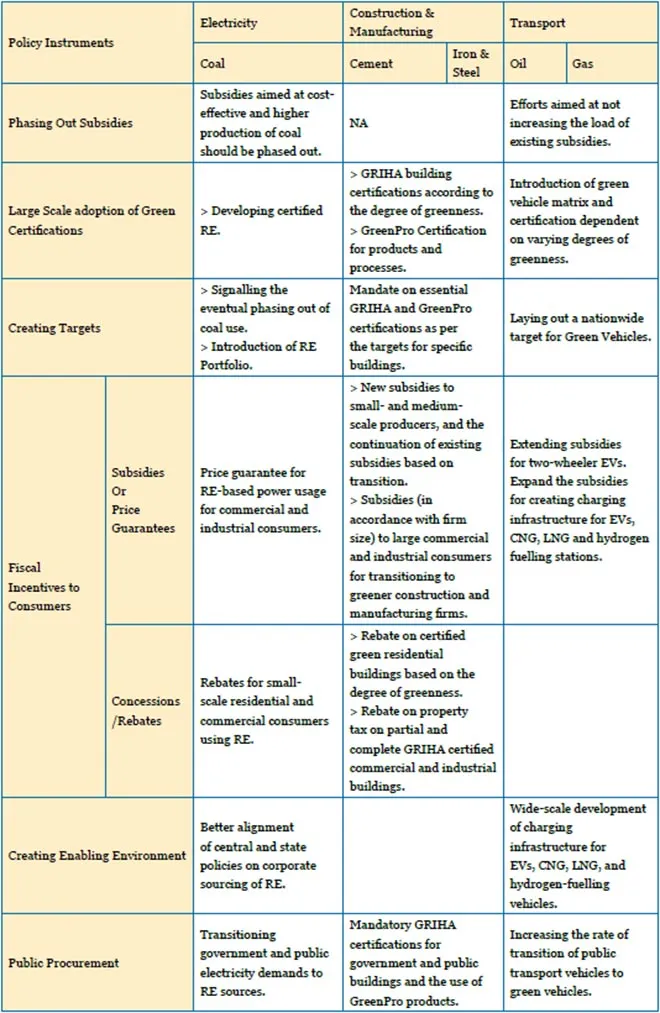

Policy instruments

Given these sectors’ contribution to GHG emissions and the future growth potential, it is important to address emissions from them. The overview of the sectors in consideration further clarifies the importance of reducing emissions by bridging demand and market access gaps. This section lists policy instrument suggestions for stimulating the demand for alternative or green industries.

A. Phasing out harmful subsidies: To help the market for green products prosper, a policy must first ensure that subsidies to environmentally harmful sectors are removed. This will boost the demand for greener alternatives. Thus, < style="text-decoration: underline">gradually phasing out harmful subsidies aimed at cost-effective production and consumption of environmentally unsustainable products and processes allows market signals to align with the true values of polluting sectors. This is the first step towards incentivising the emergence of green industries.<42>

- As explored in the chapter on carbon pricing, subsidies for fossil fuels, like coal are seven times more than subsidies for RE. In 2019-20, coal subsidies were estimated at US$2.3 billion.<43> < style="text-decoration: underline">Phasing out harmful subsidies aimed at cost-effective coal production exposes consumers to the real cost of coal, incentivising the shift to other sources of electricity production, i.e.

RE.

- Phasing out oil and gas subsidies entirely might have a significant negative impact on the poor, due to the lack of alternative green and affordable modes of transport. However, between 2017-18, oil and gas subsidies saw a 65-percent increase.<44> Efforts should be made to not increase the load of existing subsidies on oil and gas.

B. Large scale adoption of green certifications: A large-scale adoption and promotion of green certifications by the government will impress upon the market the importance of and possible fiscal benefits associated with such certifications. As a result of the BEE certifications, for instance, not only did producers transition to developing more energy-efficient products, but people also moved towards products with green ratings, thereby fostering a larger market for green industries.<45>

- < style="text-decoration: underline">Buildings that use energy-efficient systems and are overall less environmentally taxing must be identified and given GRIHA certifications.<46> This could begin with new commercial, industrial and government buildings, and eventually include residential and old buildings.

- In parallel, the use of < style="text-decoration: underline">GreenPro Certification<47> must be widely adopted for identified green-building materials, and industrial and consumer products.

- < style="text-decoration: underline">Certified RE must be developed and can be supplied through multiple electricity supply companies, allowing consumers to choose their RE supplier.<48>

- A < style="text-decoration: underline">green vehicle matrix must be developed, wherein passenger vehicles using CNGs, heavy transport vehicles carrying freight and using LNGs, and vehicles using hydrogen fuels must be identified, with varying levels of green being given appropriate certifications. For instance, EVs could be awarded a higher level of green vehicle certification.

C. Creating mandates and targets: The creation of mandates and targets by governments support increased production and demand for green industries. This signals India’s prioritisation of green products and incentivises the transition to green goods and processes.<49>

- Since a large proportion of India’s energy needs is dependent on coal, a blanket ban would not work. However, < style="text-decoration: underline">creating targets towards the eventual phasing out of coal-use for electrification could incentivise consumers to shift to other sources of electricity generation.

- The government must introduce an < style="text-decoration: underline">RE portfolio, whereby every industry must fulfil a part of their electricity generation needs using RE sources.

- < style="text-decoration: underline">A gradual mandate must be released that requires every new commercial, industrial and government building (and eventually, residential and old buildings as well) to hold a certification for partial (specifying the target) or complete green materials used (GreenPro and GRIHA certifications). The Andhra Pradesh government has already pushed for making ECBC mandatory for obtaining building approval.<50> At the national level, these mandates can be first deployed in industrial parks and SEZs, with the provision of special rebates.

- Expanding on the already existing target for EVs for 2030<51>, a target could be set for the newly devised certification for green vehicles in the country.

D. Fiscal incentives: The easiest way to promote demand for a particular industry is to make it more cost-effective than its competitors. Thus, increased affordability will enable consumers to switch to greener industries.<52>

- In India, around 91 percent of RE subsidies are for production, while the remaining schemes support both production and consumption. This creates the need for focused subsidies for end consumers on the use of RE for electrification needs, in addition to the already introduced subsidies such as low GST and viability gap funding.<53> Introducing a price guarantee for RE-based power usage for industrial consumers and rebates for small-scale consumers using RE at home will incentivise end consumers to increase the demand for renewable sources of energy for electrification in their industries and homes.

- To allow small and medium industrial producers of cement, iron and steel to switch to greener and more efficient processes, they can be provided with fiscal incentives.<54> These can include land-related support; expenditurerelated incentives such electricity duty exemptions, rebates, and subsidies; and capital investment-related incentives. These special incentives for small and medium producers, as well as existing subsidies to steel, cement and iron producers, should be contingent on their level of transition while ensuring that there is no green washing.

- Large industrial and commercial consumers of iron and steel, and cement can be given subsidies to allow them to transition to greener manufacturing and construction companies. These must be in accordance with firm sizes, such that smaller firms get bigger subsidies to switch.

- Rebate can be offered for certified green residential buildings located in urban areas where land value is usually high and additional rebate for rural and semi-urban areas, both based on the degree of greenness. Additionally, rebate can be extended to property tax for partially and fully GRIHA-certified commercial and industrial buildings, based on the degree of greenness.

- Since India is a two-wheeler dominant country, and the sales for EVs in 2018 were only 0.3 percent of total two-wheeler sales,<55> the government must extend the already available subsidies for buying two-wheeler EVs in India.

- The success of CNG in Delhi has been a testament to the benefits of technology, which allows retrofitting in existing vehicles for a green transition.<56> This can be applied to freight as well as passenger vehicles, by subsidising the retrofitting procedure and facilitating the transition to CNG, LNG and hydrogen fuels. Further, the subsidies on creating charging infrastructure (for EVs, CNG, LNG, and hydrogen-fuelling stations) can be expanded.

E. Public procurement: The best tool for the government to increase the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of cleaner sources of energy is the undertaking of mandatory green procurement requirements. In India, this will also allow governments to create a demand for green products, especially since 30 percent of the country’s GDP is spent on public procurement. Considering the massive size of public spending, the public sector in India can be a prime driver towards sustainable production and consumption, creating both environmental and economic benefits. Furthermore, public procurement would highlight “greening” as a government priority and provide clear directives and expectations to politicians and procurement officials.<57> < style="text-decoration: underline">The first step will be to introduce a clear < style="text-decoration: underline">mandate and targets for the procurement of sustainable items in tenders.

- A clear transition of government and public resources to cleaner and less polluting RE sources of electrification will constitute the first step towards establishing the state’s green priority. For instance, electrification in parks must be shifted to RE sources.

- New government and public buildings must aim at getting the highest level of GRIHA certification. The recent government-initiated “Housing for All” programme<58>, for instance, presents significant green building potential. Further, efforts must be made to use only GreenPro products for government requirements.

- There must be a concerted effort to use retrofitting to increase the rate of transition of public transport vehicles (such as intra- and inter-city buses) to green vehicles, aimed to eventually achieve successful targeted conversion to EVs.

F. Creating enabling environment: The policy interventions mentioned here will only work if the environment is suitable for their optimal utilisation. This makes it equally important to create policies that help bridge gaps in effectiveness to facilitate those that aim at improving access to green products in the market.

- While India is heavily focused on EVs and is making efforts to provide affordability for the product, the lack of charging stations is an obstacle to the adoption of these green vehicles. Public investment and nationwide development of charging infrastructure<59> are therefore necessary to encourage the usage of EVs.

- Charging stations for CNGs, LNGs, and hydrogen fuels must also be developed. This can also be done in collaboration with various up and coming private-sector start-ups in the line.

- Better alignment between state and central policies on corporate RE sourcing and its enforcement will help bridge implementation gaps.<60> The recent mandate by the Centre, that states must pay RE generators and clear their dues, reflects a disconnect between Central and states policies.

Additional policy instruments

- Green marketing:< style="font-size: 16px"> Currently, there is a lack of information for consumers and producers regarding the availability and affordability of green technology, and about phasing out harmful polluters. There is a need to invest in awareness campaigns. Green marketing must especially focus on consumers, to allow them a chance to opt for greener products, incentivised by the available subsidies and the need to switch targets. At the same time, green marketing will allow producers—particularly, the small- and medium-scale enterprises—to learn about targets and public procurement and align their production strategies accordingly.<61>

- Monitoring and evaluation of subsidies: As illustrated, it is important to provide useful subsidies while phasing out the harmful ones. However, subsidies must be identified as useful, outdated, or harmful by monitoring existing and new subsidies for green industries and polluting industries. This will help improve the transferring of resources for better use and the filling of gaps to create a greater market for green goods. Compulsory environmental audits in buildings, and monitoring the gaps in EV subsidies, for instance, can help formulate a more fruitful industrial policy.<62>

Impact

The suggested policy instruments are intended to increase market access and boost the demand for green industries as alternatives to conventional highly polluting industries. The impact would create environmental benefits whilst also fostering green growth for India.

Electricity and heat generation: Investments in RE have the potential to create thrice as many jobs as compared to investments in fossil fuels such as coal. Furthermore, the creation of clean energy and closing the energy access gap are good business, since the cost of renewables has fallen enough to build new RE capacities instead of operating on existing coal capacities.<63> In India, 50 percent of coal production will become uncompetitive by 2022, reaching 85 percent by 2025.<64> If subsidies enhancing the competitiveness of coal production are phased out, this figure will be much higher. Thus, India can become a true global superpower in the fight against climate change if it expedites its shift from fossil fuels to RE.

Construction and manufacturing: Industry projections suggest that India’s green building market for new buildings is estimated to be somewhere between US$30 billion to US$ 40 billion.<65> Additionally, a recent TERI report estimated that investments in green building and RE have the potential to generate 2.4 million unskilled and 6.1 million skilled jobs in India.<66>

Transportation: The global automotive market’s projected shift towards EVs creates a huge opportunity for India. According to a government blueprint, the EV sector is expected to create 10 million jobs in India and be a USD 206 billion opportunity.<67> Given the country’s increased focus on LNG and CNG, the total consumption for these greener fuels is set to witness a projected year-on-year increase of 28 billion cubic metre (BCM) during 2019-25. Finally, as the Asia Pacific region prepares to increase its LNG imports, from 69 percent in 2019 to 77 percent by 2025, India has the potential to supply this increased demand to a large extent and account for 20 percent of incremental trade.<68>

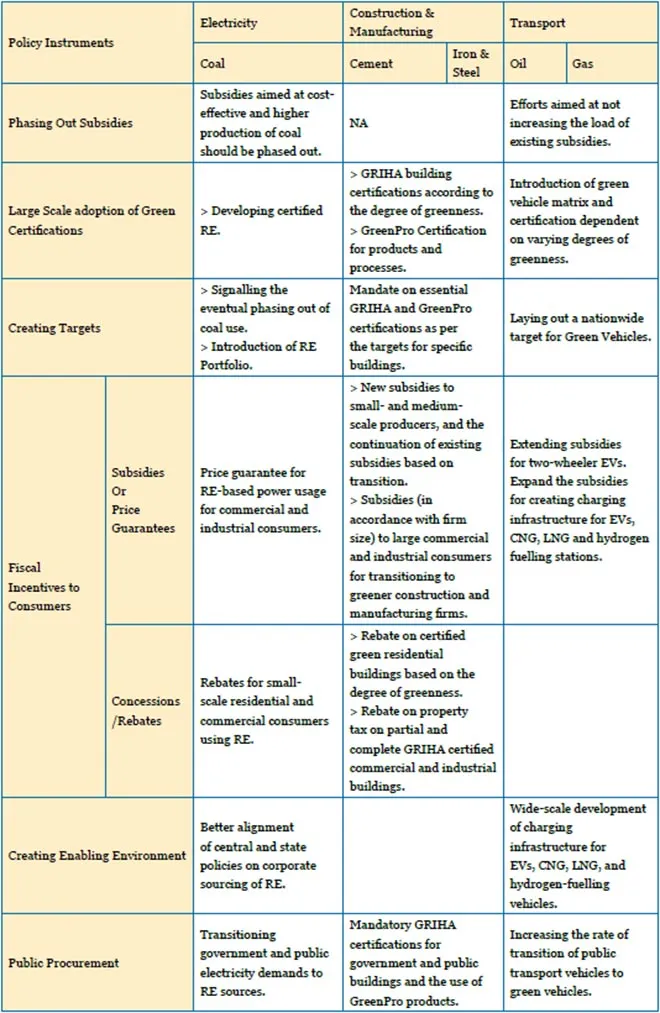

Table 1: Summarised Recommendations on Policy Instruments

Source: Author’s own

Source: Author’s own

Conclusion

For a green industrial policy to work, both market demand and supply must be stimulated. So far, the Government of India has developed policies that enhance both supply and demand, but these have stressed disproportionately more on the former.

Moreover, for the policies aimed at incentivising demand creation for green products and green transition in the country, there is substantial gap between the guidelines and implementation. The main reason for this is the absence of a regulatory framework to operationalise the guidelines. For instance, the National Cooling Action Plan proposes important strategies for creating a greener India; however, it is far too ambitious given the lack of any accompanying structural support.<69> Unless they are backed by adequate and essential regulatory and institutional bodies, action plans aimed at transitioning the Indian market and industries to greener versions are bound to fail. It is therefore important to not only bridge the demand gap for an optimal transition to green growth, but also create appropriate legal frameworks to actualise their potential.

An increase in the demand for green products not only can boost sustainability, but also create a huge potential for fostering economic growth and increasing jobs in the country in a post-pandemic world.

This chapter focused on policy interventions aimed at shifting consumption perceptions and preferences from traditionally polluting sectors to alternative green sectors. It examined the largest emitters in India — electrification and heat generation, construction and manufacturing, and transportation — and suggested policy recommendations aimed at increasing the demand for already established alternatives in these sectors. Policy interventions suggested are phasing out harmful subsidies, large-scale adoption of green certifications, fiscal incentives to consumers, creating an enabling environment, and public procurement. Additional policy instruments include green marketing, aimed at increasing knowledge and awareness about green products, its benefits, and the financial incentives associated with them; and monitoring and evaluation of existing subsidies in these sectors to alleviate the demand gaps.

An increase in the demand for green products not only can boost sustainability, but also create a huge potential for fostering economic growth and increasing jobs in the country in a post-pandemic world. Given the rapid global shift towards green sources, investing in green industries will further India’s prominence and centrality in the global climate action. Undoubtedly, the first step towards this is to foster demand at home.

Endnotes

‘Green market’ here refers to a market for environmentally sustainable products and processes.

Given the theme of the report, Energy and Industrial Processes are the focal points for this chapter.

As explained further in the chapter, the largest emitters in manufacturing and construction industry are cement, iron and steel industries.

Here, we are including coal and lignite in fossil fuels.

Scope 2 accounts for GHG emissions from the generation of purchased electricity consumed by a company.

The mission includes the Perform Achieve and Trade (PAT); the Energy Efficiency Financing Platform (EEFP); Framework for Energy Efficient Economic Development (FEEED); and the Market Transformation for Energy Efficiency (MTEE).

These are called RE 100 companies.

Most recently, the Union Budget 2021-22 laid special attention to infrastructure development.

India’s rapid growth in oil consumption is mainly driven by the transport sector.

They contain 80-85 percent of carbon by weight.

Projections suggest 6559 billion tones-km (freight traffic) and 163,109 billion passenger km (2031-32).

Policies incentivising gas-driven mobility.

Around 90 percent of EV support is for consumption, aiming to lower prices for faster adoption. The balance of approximately 10 percent is made up of schemes that support both production and consumption.

Setting up city gas distribution networks, converting public transport to CNG, and creating green corridors for intercity

traffic.

California Solar Initiative, launched by the city of California, provides similar extensive rebates to small-scale consumers to promote the usage of RE.

<1> United Nations Industrial Development Organisation, Green Industry – Policies for Supporting Green Industry, May 2011, Green Industry Platform.

<2> Sabita Mahapatra, ‘A study on consumers perception for green products: An empirical study from India’, International Journal of Management & Information Technology, 2013.

<3> Mayank Bhatia and Amit Jain, ‘Green Marketing: A Study of Consumer Perception and Preferences in India’, Electronic Green Journal, 2014.

<4> Vishnu Nath, and et al., ‘Green Behaviors of Indian Consumers’, International Journal of Research in Management, Economics and Commerce, 2012.

<5> Lay Peng Tan, Micael-Lee Johnstone, and Lin Yang, ‘Barriers to green consumption behaviours: The roles of consumers’ green perceptions’, Australasian Marketing Journal, 2016.

<6> Beibei Yue and et al, ‘Impact of Consumer Environmental Responsibility On Green Consumption Behavior In China: The Role Of Environmental Concern And Price Sensitivity’, Sustainability, 2020.

<7> ‘Consumer Perception Towards Green Products And Strategies That Impact The Consumers Perception’, International Journal Of Scientific & Technology Research, 2019.

<8> ‘This Interactive Chart Shows Changes in The World’s Top 10 Emitters’, World Resources Institute, December 10, 2020.

<9> ‘GHG Platform India’, Ghgplatform-India.Org, 2021.

<10> ‘GHG Platform India’, Ghgplatform-India.Org, 2021.

<11> ‘This Interactive Chart Shows Changes in The World’s Top 10 Emitters’, World Resources Institute, December 10, 2020.

<12> ‘Sector By Sector: Where Do Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Come From?’, Our World In Data, September 18, 2020.

<13> ‘Overview Of The Power Sector’, Parliamentary Legislative Research India, 2021.

<14> Central Electricity Authority, Ministry Of Power, Government Of India, 2020.

<15> ‘GHG Emissions From India’S Electricity Sector’, Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation, 2017.

<16> ‘GHG Emissions From India’S Electricity Sector’, Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation, 2017.

<17> ‘India 2020 - Energy Policy Review’, Niti Aayog and IEA, 2020.

<18> ‘5-Fold Increase In Clean Energy Jobs In 5 Years: India’, NRDC, July 14, 2019.

<19> ‘India 2020 - Energy Policy Review’, Niti Aayog and IEA, 2020.

<20> Atul Mudaliar, ‘Corporate Renewable Energy Sourcing: The Way To 100% Renewable Electricity In India’, RE100, September 14, 2020.

<21> ‘India 2020 - Energy Policy Review’, Niti Aayog and IEA, 2020.

<22> ‘Climate And Business Partnership Of The Future - CDP India Annual Report 2019’, Carbon Disclosure Project, 2020.

<23> ‘Climate And Business Partnership Of The Future - CDP India Annual Report 2019’, Carbon Disclosure Project, 2020.

<24> Vivek Gilani, ‘Carbon, Cost, Community, Climate’, CBalance.in, December 10, 2013.

<25> ‘Green Manufacturing Energy, Products And Processes’, Confederation of Indian Industries, 2011.

<26> ‘Existing and Potential Technologies For Carbon Emissions Reductions In The Indian Cement Industry’, International Finance Corporation, 2011.

<27> ‘Green Manufacturing: Opening New Avenue For Growth Of Manufacturing’, Journal Of Manufacturing Excellence, 2011.

<28> ‘Cement’, Bureau Of Energy Efficiency, 2021.

<29> ‘Indian Cement Sector SDG Roadmap’, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2018.

<30> ‘Iron & Steel Industry In India: Production, Market Size, Growth’, IBEF, 2021.

<31> Jocelyn Timperley, 'The Carbon Brief Profile: India’, Carbon Brief, March 14, 2019.

<32> ‘Towards Low Carbon Steel Sector’, TERI, 2021.

<33> ‘Iron And Steel – Analysis’, IEA, 2019.

<34> Bureau Of Energy Efficiency, Government of India, 2020.

<35> ‘National Steel Policy (NSP)’, Ministry Of Steel, Government of India, 2017.

<36> ‘Carbon Emissions By India’S Steel Sector To Triple By 2050’, The Economic Times, February 4, 2020.

<37> ‘Supply Chains As A Game-Changer In The Fight Against Climate Change’ BCG Analysis, 2021.

<38> ‘The Road Transport Year Book 2016-17’, Ministry Of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India, 2019.

<39> ‘Transport - Mitigation of Climate Change - Working Group III, Fifth Assessment Report’, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018.

<40> ‘Moving To 2032’, National Transport Development Policy Committee, 2014.

<41> ‘Decarbonising India’s Transport System Charting the Way Forward’, The International Transport Forum, 2021.

<42> ‘Policy Instruments For Resource Efficiency Towards Sustainable Consumption And Production’, SCP Centre, 2006.

<43> ‘Mapping India’s Energy Subsidies 2020: Fossil Fuels, Renewables, And Electric Vehicles’, The International Institute For Sustainable Development, 2020.

<44> ‘Mapping India’s Energy Subsidies 2020: Fossil Fuels, Renewables, And Electric Vehicles’, The International Institute For Sustainable Development, 2020.

<45> ‘Policy Instruments For Resource Efficiency Towards Sustainable Consumption And Production’, SCP Centre, 2006.

<46> ‘GRIHA Rating’, Green Rating For Integrated Habitat Assessment, 2021.

<47> ‘Greenpro’, Confederation of Indian Industries, 2021.

<48> Atul Mudaliar, ‘Corporate Renewable Energy Sourcing: The Way To 100% Renewable Electricity In India’, RE100, September 14, 2020.

<49> Altenburg, T., and Assmann, C., ‘Green Industrial Policy. Concept, Policies, Country Experiences’, UN Environment and German Development Institute, 2017.

<50> ‘ECBC Mandatory For Getting Building Approvals In State’, The Hindu, October 19, 2020.

<51> ‘Electric Vehicles A $206 Billion Opportunity For India By 2030’, Business Today, December 8, 2020.

<52> Eaton, D., and Sheng, F., ‘Inclusive Green Economy: Policies and Practice’, Zayed International Foundation for the Environment and Tongji University, 2019.

<53> ‘Mapping India’s Energy Subsidies 2020: Fossil Fuels, Renewables, And Electric Vehicles’, The International Institute For Sustainable Development, 2020.

<54> ‘Towards Low Carbon Steel Sector’, TERI, 2021.

<55> ‘Electric Vehicle Sales In India Up 20% In 2019-20’, Mint, April 20, 2020.

<56> Karan Shah, ‘Retrofitting Of EVs: The Need To Revisit Government Policies To Realize India’S EV Dream’, BW Businessworld, March 15, 2021.

<57> ‘Policy Instruments For Resource Efficiency Towards Sustainable Consumption And Production’, SCP Centre, 2006.

<58> ‘Housing For All’ Bringing Positive Change In Lives Of Poor, Middle-Class Families: PM Modi’, BW Businessworld, January 1, 2021.

<59> ‘Developing Infrastructure To Charge Plug-In Electric Vehicles’, Alternative Fuels Data Center, US Government, 2021.

<60> Atul Mudaliar, ‘Corporate Renewable Energy Sourcing: The Way To 100% Renewable Electricity In India’, RE100, September 14, 2020.

<61> Mayank Bhatia and Amit Jain, ‘Green Marketing: A Study of Consumer Perception and Preferences in India’, Electronic Green Journal, 2014.

<62> Eaton, D., and Sheng, F., ‘Inclusive Green Economy: Policies and Practice’, Zayed International Foundation for the Environment and Tongji University, 2019.

<63> ‘India A ‘Global Superpower’ In Fight Against Climate Change, Secretary-General Says At Memorial Lecture, Calls For Shift From Fossil Fuels To Clean Energy’, UN.org, August 28, 2020.

<64> ‘Moving To 2032’, National Transport Development Policy Committee, 2014.

<65> ‘India Green Building Market Opportunity’, Research and markets, 2016.

<66> ‘Future Is Green Job Market’, India Today, January 18, 2019.

<67> ‘‘Electric Vehicles A $206 Billion Opportunity For India By 2030’, Business Today, December 8, 2020.

<68> ‘India To Drive Global Gas Demand Post-Slowdown, Output To Rise Too’, Business Standard, June 11, 2020.

<69> ‘New Draft India Cooling Action Plan, Released Recently By Union Environment Ministry, Is Grossly Inadequate In Its Scope And Ambition – Says CSE’, CSE India, September 18, 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the new publication — Reconciling India’s Climate and Industrial Targets: A Policy Roadmap.

This article is part of the new publication — Reconciling India’s Climate and Industrial Targets: A Policy Roadmap.

PREV

PREV