In early January 2016, an inter-ministerial meeting – chaired by India’s Road Transport and Highways Minister Nitin Gadkari, and attended by Oil Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, Heavy Industries Minister Anant Geete and Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar – was convened. It was decided at the meeting that the Government would skip Bharat Stage (BS) V emission norms altogether and leapfrog from BS-IV to BS-VI directly by 1st April 2020, in an apparent bid to curb vehicular pollution in the country.

Two years later, in October 2018 the Supreme Court re-affirmed the decision by saying that no BS-IV vehicle shall be sold across the country with effect from 1st April 2020.

BS-VI is the most advanced emission standard for automobiles and is equivalent to current Euro-VI norms applicable across Europe. With the introduction of BS-VI, on-board diagnostics (OBD) will be mandatory for all vehicles. The OBD unit is supposed to identify likely areas of malfunction and thereby ensure that the advanced emission control device fitted in the automobile runs at optimum efficiency throughout the vehicle’s life. Similarly, introduction of a fuel injection system will be mandatory for two-wheelers. The new norms are expected to result in drastic reduction in the difference in carbon emission between diesel and petrol engines.

Though executed with the noble intention to save the environment, what did this leap from BS-IV to BS-VI norms imply for the manufacturers and the consumers?

Auto manufacturers have had to increase their investment to upgrade existing models and create new models in order to comply with the new norms. Apart from increasing costs, this has also translated into deceleration in the launch of new models, particularly for companies like Maruti Suzuki and Hero Motocorp, whose portfolios are larger than that of other competitors.

For consumers, new BS-VI norms will result in increased prices of vehicles – diesel vehicles and economy-segment motorcycles are expected to cost more.

The decision on BS-VI, therefore, created sufficient disruption both in the supply and demand sides. Manufacturers would like to see how demand changes over time. Consumers will wait for the new BS-VI compliant cars and two-wheelers to be unveiled, and then exercise their choice based on market feedback.

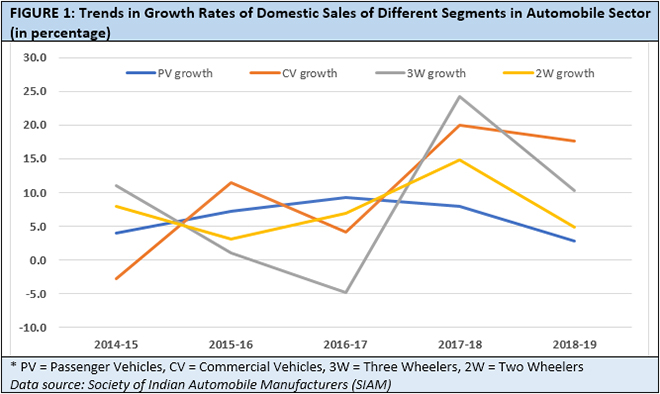

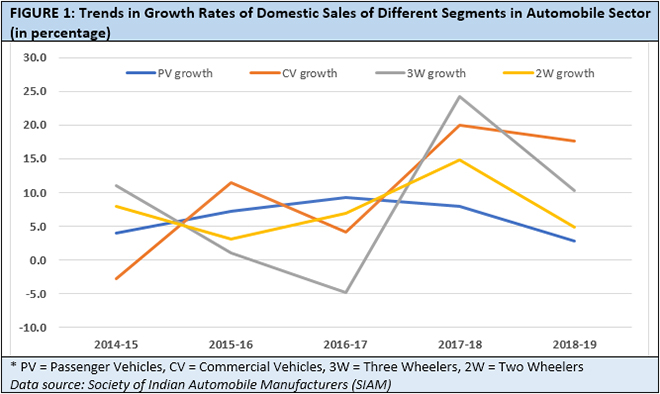

By the time the economy arrived at the end of financial year 2018-19, signs of a slowdown in the automobile sector were evident, as can be observed in Figure 1. This is not to suggest that the decision to go directly to BS-VI was the sole reason behind the slowdown, but the leapfrogging definitely created distortions in both supply and demand.

Figure 1 also demonstrates that there has been a general slump in the auto sector sales growth in 2018-19, after a brief revival in 2017-18. The selling volume of the auto sector principally comes from passenger vehicles and two and three-wheelers segments. These segments experienced sizeable reduction in growth by the end of March 2019. This slump has been attributed to the lack of sectoral demand due to the prevailing economic slowdown.

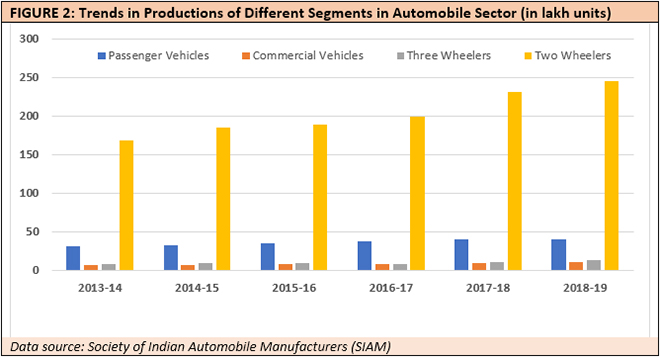

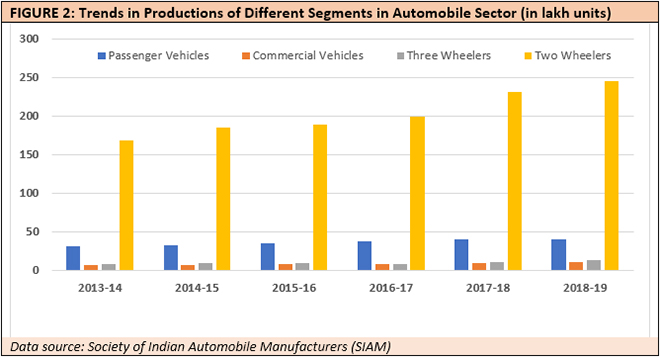

Possibly with an expectation of a revival in the latter part of 2019, auto manufacturers kept ramping production in absolute numbers – albeit at a slower pace (Figure 2). In terms of number of units produced, production of two-wheelers went on, more or less, unabated. However, the downside of such positive expectation has been an inventory pile-up.

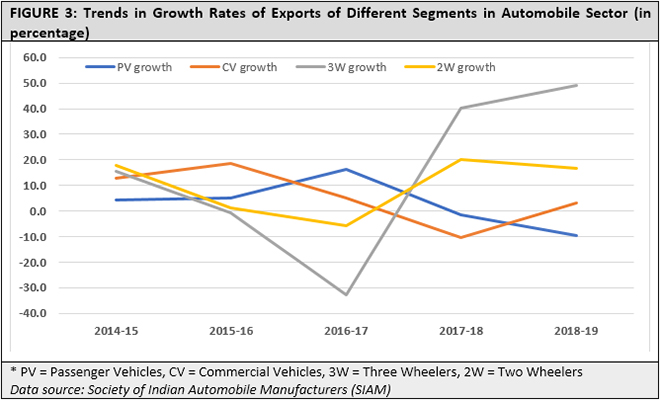

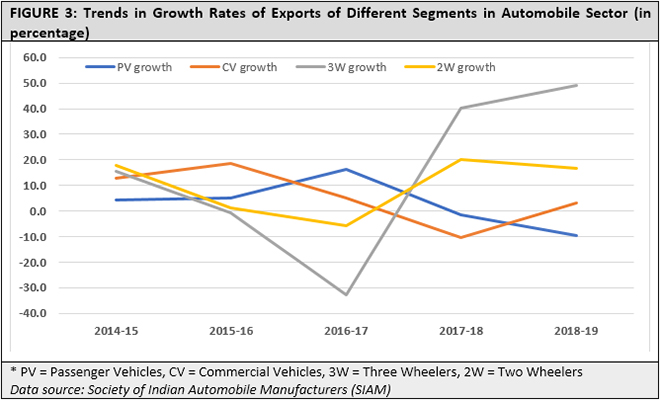

A positive expectation of a rise in future demand possibly originated from a steady growth in automobile exports in recent years, apart from a chance of revival during the festive season in the latter half of the year. But, Figure 3 injects scepticism on that count as passenger vehicles and two-wheeler exports show falling rates of growth in 2018-19.

A positive expectation of a rise in future demand possibly originated from a steady growth in automobile exports in recent years, apart from a chance of revival during the festive season in the latter half of the year. But, Figure 3 injects scepticism on that count as passenger vehicles and two-wheeler exports show falling rates of growth in 2018-19.

Subsequently, the slowdown continued unabated even in the current financial year. July sales data revealed a 31% decline in the sales of India’s top five automobile manufacturers which account for 85% of total sales. Manufacturers now believe that the slowdown is not going to fade away immediately, it may even worsen in the near future.

The slowdown has started having a cascading effect on auto component makers and retail dealers. The Automotive Component Manufacturer’s Association of India (ACMA), in a statement, has said that there could be as many as 1 million layoffs if the trend persists. The Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations (FADA) has reported the loss of around two lakh jobs in automobile dealerships across the country in the last three months. Auto components cluster in locations like Adityapur may face greater challenges as these component clusters are dependent on only one segment of the industry (in Adityapur’s case, commercial vehicle manufacturing at Jamshedpur).

Meanwhile, the Union Budget 2019 has added another tricky element to this current cauldron of disruption in the form of electric vehicles (EVs). The Union Government has now explicitly reiterated its intention to “leapfrog India as a global hub of manufacturing of EVs” through various measures like reduction in GST rates, tax incentives on loans to purchase EVs, etc.

Like the decision to skip BS-V and jump to BS-VI, the gains in terms of reduction of city pollution by shifting to EVs is expected to be substantial, apart from the potential reduction in oil import bills. But is the industry ready for such a jump to another technology? Or is this going to further disrupt an already beleaguered sector?

There is neither a long-term policy document regarding EVs nor a clear statement of timelines. The Government in 2017 mentioned that it would shift to 100% EVs by 2030, but diluted that in 2018 from 100% to 30%. NITI Aayog, one of the prime advocates of transition to EVs in India, suggested that 40% of all cars used by taxi aggregators like Ola and Uber should be EVs by 2026. The government think tank also proposed that all new cars sold for commercial purposes after 2026 should be EVs. This is more of an ad hoc-ism than a considered policy roadmap.

India currently lacks the necessary technological know-how to fulfil the ambition to shift to EVs in the immediate future. This is bound to have multiple repercussions. First, there is an element of cost escalation in terms of R&D for increasing the efficiency of EVs and making them relatively affordable. Second, there will be barriers to erect necessary charging/swapping infrastructure. Third, evolving battery technology and chemistries for EVs will be a serious impediment in their roll-out. Last and most important, the resultant higher cost of the vehicle and higher running cost of charging/swapping batteries may make EVs not so viable for the biggest group of consumers – the middle classes.

A hurried introduction of EVs on Indian roads is likely to help Chinese companies flood the Indian automotive market. Instead of transforming into a hub of EV manufacturing, if India becomes a net importer and an assembling centre of EVs then it will be a most unfortunate outcome.

While the auto industry as a whole is going through an unprecedented slump in recent times, it is quite baffling to see the hasty introduction of newer unknown policy factors in the mix – in terms of emission standards and new technology paradigms. The time has probably come to hit the pause button and rethink the future of the Indian automobile sector.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

A positive expectation of a rise in future demand possibly originated from a steady growth in automobile exports in recent years, apart from a chance of revival during the festive season in the latter half of the year. But, Figure 3 injects scepticism on that count as passenger vehicles and two-wheeler exports show falling rates of growth in 2018-19.

A positive expectation of a rise in future demand possibly originated from a steady growth in automobile exports in recent years, apart from a chance of revival during the festive season in the latter half of the year. But, Figure 3 injects scepticism on that count as passenger vehicles and two-wheeler exports show falling rates of growth in 2018-19.

PREV

PREV