The world lost about 400 million full-time jobs in the second quarter of 2020 (April-June) due to the COVID19 pandemic, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO). <1> The ILO also pointed out that about 59 per cent full-time jobs have been wiped out in the Asia-Pacific region.

The situation in India is alarming — over 122 million people are jobless with no prospects of finding meaningful work in the short term; lay-off rates in large companies have increased; <2> Huawei cut its India revenue target for 2020 by up to 50 percent and laid off more than half of its staff; <3> and Reliance Industries, one of India’s largest private companies, announced pay cuts of up to 50 percent for some top oil and gas division employees. <4> In terms of high-growth companies, Swiggy laid off over 1,000 people; Ola let go of 1,400 employees; ShareChat, an Indian video-sharing social networking service, laid off about 100; and Zomato fired 13 percent of its staff. <5>

Are the lost jobs coming back? It is hard to say at this point. Startup hiring might improve marginally but they do not employ nearly as many people as those seeking opportunities. Governments are struggling to get economies back on track, and with intense pressure on the healthcare sector, providing stimulus to other sectors will not be easy.

Are the lost jobs coming back? It is hard to say at this point.

Millions are likely to be left to fend for themselves. They will have to reach out to their networks to explore new roles and find or create opportunities for themselves. As in previous recessions, many iconic companies will be born that will go on to create enormous financial wealth. They will become the employers of choice in the coming decades. But can people wait for that to happen?

In the short term, people will need to learn to monetise their skills and create unconventional economic opportunities for themselves. Waiting for the economy to bounce back is not the smartest recruitment strategy in the COVID-19 era.

Erstwhile side hustles will become full blown jobs, creating a wave of micro-entrepreneurs who will have the arduous task of finding their niche and figuring out a reasonable business model. High-growth software startups will be accompanied by a new category of hyper-local or niche-serving creators/micro-entrepreneurs.

Waiting for the economy to bounce back is not the smartest recruitment strategy in the COVID-19 era.

People are also likely to have a portfolio of professions. For instance, one person could be an Uber driver during the day, a digital media strategist in the evening, a task-rabbit hustler post-dinner and a writer/musician/gamer monetising their content late at night.

Exploring the passion economy

The experience of Coss Marte, the founder of Conbody, a prison-style fitness bootcamp that hires ex-cons to teach fitness classes, can be a useful example to navigating the post-COVID-19 world. Born to poor immigrant parents from the Dominican Republic, Marte started dealing drugs in his teens and was making more than US$2 million a year before getting caught. <6> He spent four years in prison where he discovered his passion for fitness and eventually figured out how to transform it into a viable profession. This kind of passion-centric job creation will drive the economic engine of the 21st century.

According to economist Adam Davidson and the recent future of work report published by venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, <7> the gig economy and the “Uber for X” model will at least, in part, make way for the passion economy where micro-entrepreneurs like Marte monetise their individuality and creativity.

A key component of the passion economy is storytelling.

Marte’s fitness classes are good and his subscription-based business model makes sense, but his success cannot be attributed to them. A key component of the passion economy is storytelling and Marte tells a gripping story through his business. It creates a strong bond between customers and instructors.

In addition to becoming fit, the customers are actually involved in the redemption of their instructors. Unlike other gyms where hourly paid instructors change every few months, Conbody instructors are there for life. Marte’s genius is that he has taken objectively negative facts and found a way to tell a true story in an authentic way (something many of us will need to learn, especially if we have been fired or furloughed).

There are several other examples that demonstrate the power of storytelling in the passion economy. Dave Dahl spent 15 years in jail before setting up an organic bread company, which he sold for US$ 275 million in 2015. <8>

While the gig economy flattened the individuality of workers, the passion economy will allow anyone to monetise their unique skills or stories.

Obviously, one does not need to go to jail to create a memorable story. The larger lesson is that in the passion economy, even some of the hardest, most painful aspects of our lives (for instance, losing your job in the middle of a pandemic or getting fired on Zoom) can become core pillars of our business strategy. We do not need to appeal to everyone all the time. All we need is a small group of people who understand what we are doing and are willing to support us through subscriptions and micro-donations.

According to former Andreessen Horovitz investor Ji Lin, these stories are indicative of a larger trend called the “enterprisation of consumer.” <9> While the gig economy flattened the individuality of workers, the passion economy will allow anyone to monetise their unique skills or stories.

Platforms for passion economy

Patreon is a membership platform that enables YouTubers, podcasters, musicians and other creators to earn money by offering exclusive content to paid subscribers or “patrons.” There are many such platforms empowering micro-entrepreneurs worldwide.

People will need the discipline and the rigour to work hard, experiment fast and deliver consistently. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

People will need the discipline and the rigour to work hard, experiment fast and deliver consistently. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

Take, for instance, Vicky Bennison who read zoology in college, graduated with an MBA from the University of Bath, worked in international development and is now best known as the person behind Pasta Grannies, a YouTube channel that finds, films and monetises the talents of real Italian grannies (nonnas) making handmade pasta. <10> Inspired by Bennison, one Network Capital member who worked at a major bank and got fired in the middle of the pandemic, started a YouTube channel for cakes and breads. Within weeks, it became one of the most popular channels among certain millennials and she now earns twice as much as she earned at her previous job. <11>

While the passion economy will be immensely rewarding for creators, it will not be all fun and games. People will need the discipline and the rigour to work hard, experiment fast and deliver consistently. Unlike regular employment, creators will need to figure out human resources, accounting and legal issues themselves. Paul Jarvis, author of Company of One: Why Staying Small Is the Next Big Thing for Business, shares that today creators spend more than 50 percent of their time doing extraneous stuff. That is a colossal waste of income and potential. <12>

AI and passion economy

Instead of debating whether artificial intelligence (AI) will exacerbate job losses in the COVID-19 era, we must figure out how it can augment the productivity of creators and micro-entrepreneurs who will be the pillars of economic rebuilding in the post-coronavirus world. We need to free up time for creators to do the work they truly care about and are good at. That is how the passion economy will blossom and lead to the next wave of economic growth.

Will AI lead to job losses? Of course. Are the number of jobs in the world finite? Of course not. In the years to come, we will witness a reduction in the number of institutional jobs. Governments and enterprises will hire fewer people. Some jobs would even be outsourced to robots and algorithms.

In the years to come, we will witness a reduction in the number of institutional jobs. Governments and enterprises will hire fewer people.

This phase shift will be immensely stressful if we keep running after the next big thing or the next new technology without a sense of purpose. However, if we learn to augment our creative pursuits with meaningful stories and new age technologies, the passion economy will unleash innumerable possibilities, just like it did for Marte, Bennison and Dahl.

Building a category of one

“Competition is for losers, <13> ” says Peter Thiel, investor and co-founder of PayPal. He adds, with a twist on Leo Tolstoy’s masterpiece Anna Karenina, that every failed company is alike in that it fails to transcend competition. Thiel’s analysis is as true for businesses as it is for work and careers in the post-pandemic world. The basic laws of demand and supply tell us that it is challenging to defend what is abundantly available. That is why it makes sense to think outside the box, be a contrarian and build a category of one where your uniqueness quotient is your value proposition.

While for traditional jobs there will be more applicants per advertised position, for those exploring passion economy, there will be an opportunity to escape competition and create a category of one.

The basic laws of demand and supply tell us that it is challenging to defend what is abundantly available.

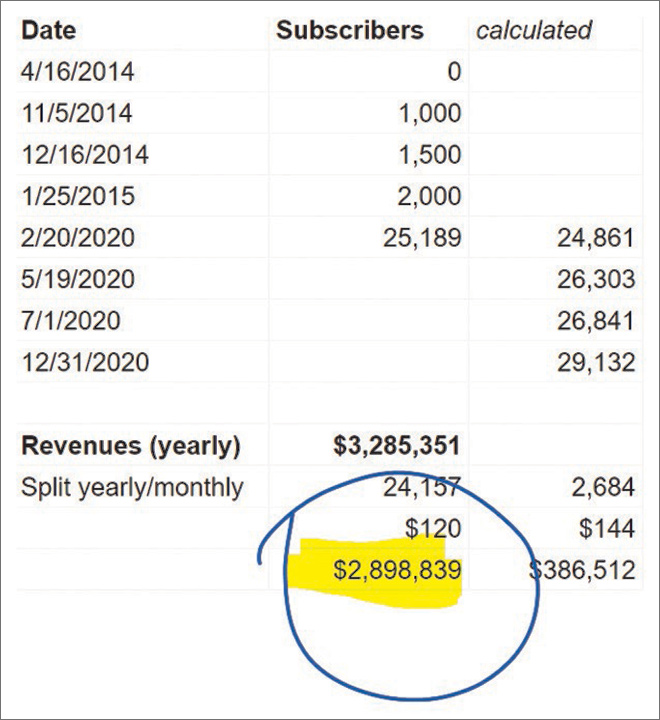

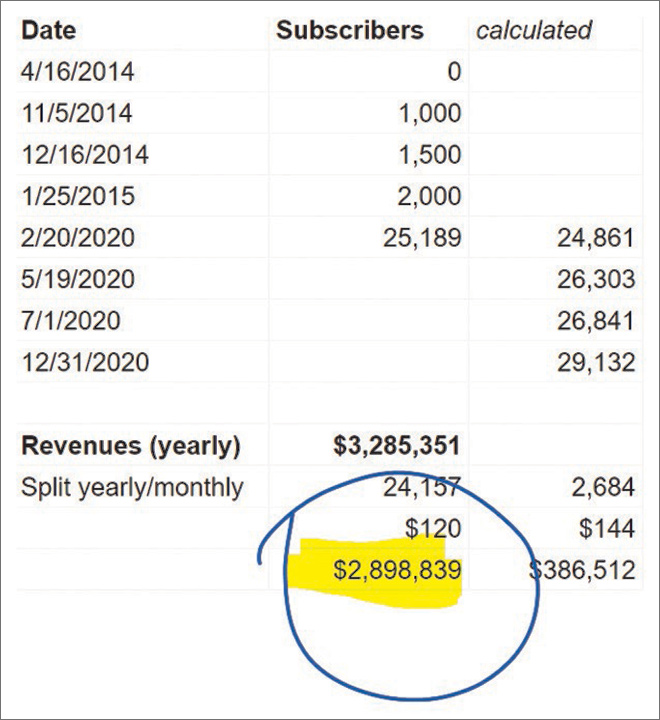

Ben Thompson got his MBA at the Kellogg School of Management, <14> worked at Microsoft and today lounges in Southeast Asia writing a newsletter on technology trends, making more than US$3 million in profits each year. <15> Thompson started by charging US$100 per year and at the last officially reported count in 2015, he had 2000 monthly paying subscribers. The picture below explains his growth trajectory. It is a conservative estimate as Thompson has not talked about numbers since 2015. <16>

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a surge in the number and quality of newsletter entrepreneurs like Thompson. Not everyone will go on to make millions of dollars, but many will be able to carve out a meaningful job that provides financial security.

Passion economy and the remote-first culture

Whether we like it or not, remote work is likely to be the new normal for creators, participants in the passion economy and for corporates around the world. Emergencies fast-forward culture. Until last year, organisational psychologists believed that within a decade, 90 percent of companies will be remote-first and globally distributed. The COVID-19 crisis has shrunk that timeline considerably.

WordPress CEO Matt Mullenweg is a pioneer in building a remote-first, distributed work company. His hypothesis was that talent is equally distributed around the world, but opportunities are not. To bridge the talent-opportunity gap, he made a conscious choice to hire the first 20 employees without meeting them. Essentially anyone could apply if they could get the work done. It was designed keeping millennials and digital nomads in mind. Today, Automattic, WordPress’s parent company, has close to 1,000 employees in 67 countries. <17>

Remote workers tend to have a slight disadvantage when it comes to collaboration, creativity and building on others’ ideas.

Despite the success of WordPress and a few other distributed work companies, there is a huge debate about the merits and shortcomings of remote work. A 2014 research paper, Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment, <18> suggested that remote workers are 13 percent more productive than their office-going counterparts. <19> But work entails more than just being productive. We need cross-pollination of ideas, lateral thinking and creativity. Remote workers tend to have a slight disadvantage when it comes to collaboration, creativity and building on others’ ideas. Their productivity gains may even be neutralised by their collaboration disadvantage. That is why an ideal distributed work culture combines elements of both.

Building productive and creative remote workspaces

How can organisations build such a culture? How can passion economy participants and creators shape productive workspaces that also augment creativity? This can be done through five steps:

First, communicate goals to all stakeholders clearly. There is a huge difference between goals and tasks. While we should set a few clear goals that can be tracked, we tend to fritter our day away conducting tasks that give us the illusion of being busy. To build a remote-first culture, we need to have clear goals and ensure that everyone understands their unique contribution towards shaping them.

Second, document everything. When people work remotely, there is no hallway conversation and water-cooler chatter. We need to communicate our thought processes and ideas succinctly so that people in different time zones can build on our work. Mullenwag explains that this process of documentation also helps as organisations scale and new people join. <20>

Third, learn to write effectively. Learning to write clearly and creating a culture where people share fully formed thoughts will go a long way towards optimising everyone’s time. Abusing instant messaging by interrupting someone else’s work must be avoided as companies adopt a remote-first outlook.

Fourth, schedule unstructured social time. The office is not just a place where work gets done. It offers a platform for social connections and friendships. Distributed work companies need to figure out a way to replicate this online.

Fifth, incentivise working remotely. Renting an office is far more expensive than paying employees/partners/freelancers to work where they like. That said, cost is not the only motivator. Incentivising remote work is also a way of expressing trust in employees, partners and stakeholders.

Making remote work work for women

The Institute for Fiscal Studies and University College London interviewed 3,500 families during the early months of the pandemic to gauge how men and women distributed chores and responsibilities in a work-from-home setup. <21> Their findings are applicable to families where both mothers and fathers were working, as well as to families where both parents were furloughed or out of work. The results are worth reflecting on:

Mothers were only able to do one hour of uninterrupted work, for every three hours done by fathers. A female interviewee said: “ is furloughed and yet my work telephone calls are interrupted by the children asking questions, while daddy is just watching Netflix.” <22>

Mothers are doing, on average, more childcare and more housework than fathers who have the same work arrangements.

The only set of households where mothers and fathers share childcare and housework equally are those in which both parents were previously working, but the father has now stopped working for pay, while the mother is still in paid work. However, mothers in these households are doing paid work during an average of five hours a day, in addition to doing the same amount of domestic work as their partner.

Mothers are doing, on average, more childcare and more housework than fathers who have the same work arrangements. Illustration: Monica Rief/Getty

Mothers are doing, on average, more childcare and more housework than fathers who have the same work arrangements. Illustration: Monica Rief/Getty

Only two percent of new mums and dads split their entitlement to parental leave. This generally leaves women in charge of establishing a routine and learning how to be a parent — usually by trial and error.

On analysing remote work for women, organisational psychologists Herminia Ibarra <23>, Julia Gillard <24> and Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic <25> offered six suggestions to make work from home/remote work work for women. <26> While most of their suggestions are directed at corporations, some ideas are applicable to passion economy participants, freelancers and micro-entrepreneurs as they deal with customers, partners and other stakeholders in the ecosystem.

First, do not make assumptions. Instead, focus that energy on collecting and analysing data. Data is known to be a powerful tool in revealing gaps, therefore, the organisation’s human resources department needs to shift to becoming more evidence-based and not rely on its intuition as much. A starting point could be viewing remote work level-by-level and ask — is there equality in terms of career benefits among the entry-level, mid-career, and executive strata?

Second, employers should change with, rather than against, their organisational culture. If the existing culture is ‘This is how we do things around here, get with it,’ then the company should accommodate some sort of flexibility and ask its management employees ‘How should we do work from home around here?’, and the answer should include paying attention to gender equality and other dimensions of diversity. Since this is a new experience for everybody, it does not make sense to continue with older organisational policies that were written when people physically went to work. While technologies such as Zoom have made things easier for both employees and the firm (wherein they provide employees with flexibility, and firms with increased efficiency), these technologies will prove to be an even greater asset if the organisation can effectively integrate them with its culture.

Third, understand that remote working (unlike the office) does not occur in an environment free of interruptions. Organisations should actively attempt to do away with any embedded assumptions about the gender-normative roles of mothers and fathers so that these biases do not influence managers’ and colleagues’ perceptions of what work from home looks like for men and for women.

Fourth, make sure the organisation is based on collaboration and fairness for all. If most employees are working from home, but some do physically come to work, management should make sure that this does not turn the office space into some sort of “VIP area of a club or the first-class section of a business lounge.” The only way to get an organisation to function effectively during this time is to strive for a balance that will essentially require organisations to examine the gender distribution at home and in the less-crowded office, ensuring an equal amount of flexibility and “hybrid” access for everyone.

Fifth, organisations should make sure that everybody (even top management) is educated about ‘company rules’. If firms hope to make work from home function effectively for everybody, it should ensure that its managers understand their colleagues’ obligations, and that all employees have access to workshops/sessions and guidance on work stress, work-life balance and inclusion. This will help employees differentiate between their personal and workspace and be empathetic to their colleagues’ work from home arrangements.

Sixth, focus on output, and keep in mind employees’ situation during the lockdown period. The firm’s performance evaluation processes and metrics should be upgraded to ensure that there is a focus on overall output. Moreover, management should be mindful of its employees’ enhanced struggles during the lockdown, and, perhaps, should consider not including assessments from that period.

Vulnerable groups: Discriminations to watch out for

Ageism, sexism, groupism and other forms of discrimination have been — and still are — rampant in many spheres of work, but unless we make structural changes, things will get worse in the post-pandemic world.

Age discrimination in the job market tends to worsen during recessions. Some employers are using COVID-19 as an excuse to get rid of their experienced workers who are paid higher wages, only to replace them with younger professionals who are eager to accept any offer. The National Bureau of Economic Research found that age discrimination goes hand-in-hand with the unemployment rate. <27> Older workers tend to be fired first and hired back last.

Jobs held by women — concentrated in the service industry — are especially vulnerable in the coronavirus economy. There is evidence that women have been laid off or furloughed at a significantly higher rate than men. <28> Research has also shown that women are more likely to carry out more domestic responsibilities while working flexibly, whereas men are more likely to prioritise and expand their work spheres. <29>

Jobs held by women — concentrated in the service industry — are especially vulnerable in the coronavirus economy.

Another threat to working women in heterosexual relationships is choosing to opt out of the workforce to manage their homes. Since children are not physically going to school, and families are forced to take on significantly more domestic labour, women tend to sacrifice their work to take care of the domestic situation at alarmingly higher rates than their partner. According to the BBC, even if women feel their jobs or incomes are relatively safe, many just cannot carry on the way they are for long. <30> Women have traditionally carried out a “second shift” at home once their workday had ended. Now most women are trying to work the two shifts at the same time, and the mental health toll has driven many to quit their jobs during the pandemic. <31>

Cognitive diversity as a design principle for the post-pandemic era

It is well known that diversity of thought, conviction and action enables better problem solving. One often ignored category is cognitive diversity — the difference in perspective or information processing styles. Tackling new challenges requires striking a balance between what we know and learning what we do not know at an accelerated pace. According to UK-based professors Alison Reynolds and David Lewis <32> a high degree of cognitive diversity generates accelerated learning and performance in the face of new, uncertain, and complex situations. Cognitive diversity and complementarity of skills are probably the two most crucial factors that will propel modern workplaces to tackle tricky challenges unleashed in the pandemic-battered modern workplace looking for revival.

People prefer to fit into the organisational culture rather than question the way things get done.

The challenge is that even though cognitive diversity is crucial, its adoption is hard. That is why it needs to be thought of as an integral element of workplace design as we regroup. The truth is that many startups and corporates try but often stumble into two bottlenecks. First, cognitive diversity is hard to detect from the outside. Reynolds and Lewis state that it cannot be predicted or easily orchestrated. Being from a different nation or generation gives insufficient clues as to how the person processes information and responds to change. The second reason is that there are cultural barriers to cognitive diversity. People prefer to fit into the organisational culture rather than question the way things get done.

One of the biggest mistakes organisations make is to only hire people who fit in to their existing culture. They should instead hire for cultural contribution. In practical terms, this means empowering employees to evolve and shape cultural norms. This also helps an organisation analyse existing challenges with a fresh perspective.

Even for micro-entrepreneurs, solopreneurs and passion economy participants, cognitive diversity will be an essential tool for broadening their focus, expanding to new customers and partnering with those who may not share their worldview.

Salaries post COVID-19: The case for wage transparency

In most developed countries, women are paid less than men for the same work. According to the statistical office of the European Union, for every US$ 100 earned by a man, a woman earns US$ 78.50 in Germany, US$ 79 in the UK and US$ 83.80 on average across the other EU countries. <33> In every OECD country, men are paid more than women. Averaging at 13.5 percent, the gender pay gap ranges from 36.7 percent in South Korea to 3.4 percent in Luxembourg. This gap persists, despite the attention, it has received, and, it is widening in some cases. <34>

It is conceivable that the wage inequity of the pre-COVID-19 era will get magnified once the pandemic is behind us.

COVID-19 has resulted in widespread job losses and in salary cuts across the board. On average, people are ready to do more work for less money. This is as true for freelancers as it is for those seeking conventional employment. It is conceivable that the wage inequity of the pre-COVID-19 era will get magnified once the pandemic is behind us. Maybe the flexibility offered by remote work comes at the cost of women’s salaries.

One solution to overcome wage inequity is wage transparency. In Sweden <35> you can find out anyone’s salary with a simple phone call. Businesses with 25 or more employees must establish an equality action plan. And companies with big pay gaps face fines if they ignore it. While naysayers might suggest that examples from Nordic countries are not representative, but studies suggest otherwise.

A 2015, PayScale study <36> surveying over 70,000 American employees, demonstrated that the more people knew about why they earn what they earn, especially in relation to their peers, the less likely they were to quit. Dave Smith of PayScale said that “open and honest discussion around pay was found to be more important than typical measures of employee engagement.” <37>

Employees are more motivated when salaries are transparent.

INSEAD Professor Morten Bennedsen <38> collaborated with Columbia Business School and Cornell researchers to conduct an empirical study to look at <39> the impact of mandatory wage transparency. In almost every context, disclosing gender disparities in pay narrows the wage gap. Further, employees are more motivated when salaries are transparent. They work harder, are more productive, and collaborate more with colleagues. Wage transparency is not a panacea, but evidence clearly suggests that it is worth a try.

Implications on mental health and wellbeing

Remote work, physical distancing and social distancing

As remote work becomes the norm, how will it impact our empathy to our colleagues and coworkers? Jamil Zaki, author of The War For Kindness, <40> explains that physical, social and emotional distance does not have to coincide. He suggests that we should start by renaming social distancing to physical distancing to emphasise that we can remain socially connected even while being apart.

If we let physical distancing lead to social disconnection, it can intensify our loneliness, which may further lead to sleeplessness, depression, cardiovascular problems and produce a similar mortality risk to smoking 15 cigarettes a day. <41>

Now, more than ever, we need empathy and to create a sense of solidarity within and outside our communities. We need to channel it to meaningfully connect with fellow sufferers, our friends, neighbours and colleagues.

Now, more than ever, we need empathy and to create a sense of solidarity within and outside our communities.

Empathy is flexible. It is an acquired skill that can be developed by training, deliberate practice, personal application and self-awareness. Zaki offers an interesting analogy. Our empathy is like a muscle, <42> left unused, it atrophies; put to work, it grows. There is, however, a catch. Empathy diminishes with time and distance. <43> In addition, as Yale University professor Paul Bloom suggests, our empathy flows most for those who look like us, think like us, seem familiar and are perceived as non-threatening. Since the specter of the coronavirus transcends time, distance and the extent of familiarity, it is a rare opportunity for us to scale our empathy and think of empowering others along the way.

Many of us blame online technologies and social media for ripping apart our social fabric. <44> It has been found that when we are anxious or stressed, we tend to aimlessly scroll through our phones and find our anxiety transformed into unmitigated panic.

While this is a fairly common use case, we should keep in mind that how we use technology is not pre-ordained. Those very tools that we love to hate are now our best hope for increasing our empathy quotient.

How we use technology is not pre-ordained.

When footage of inhabitants of the Tuscan city of Siena singing their city’s official song from their balconies started circulating on social media, Italians all over the country started sharing videos in which they also sang from their windows. This trend soon made its way to Beglium. The online group ‘België zingt … uit het raam! — La Belgique chante… de sa fenêtre!’ (Belgium sings… from the window!) built a huge community where people from across the country sang from their windows every evening. <45> Millions of citizens around the world used such online message boards, support groups and independent sites to share information, common challenges and develop innovative ideas to grapple with isolation.

Videoconferencing tools, social media apps and online support groups are playing a crucial role today by enabling us not only to work and collaborate but also to ‘hang out’ digitally. When we meet offline, we do not expect every minute to be productive. We get our work done and strengthen our social bonds with meandering discussions. Now it is the need of the hour to find ways to replicate this digitally.

The COVID-19 crisis is far from being under control. As physical distancing becomes a norm, we will all need digital spaces and support groups to transform our personal loneliness into communal empathy. Through our suffering, perhaps for the first time, billions of us have more in common than ever before.

When we meet offline, we do not expect every minute to be productive.

Grappling with regressing under lockdown

Many of us who had initially found creative ways to deal with the lockdown reported feeling irritable, withdrawn and less productive as the pandemic progressed. It turns out that feeling disoriented and directionless is not only normal but also unavoidable. Battle Mind author Merete Wedell-Wedellsborg <46> studied several prominent CEOs dealing with tough business decisions and observed that most crises tend to have three stages: Emergency, regression and recovery.

The first weeks of managing any crisis (emergency stage) can feel both meaningful and energising. Despite a drop in key business metrics such as revenue, customer engagement and profits, there is a sense of adventure and purpose in grappling with unfamiliar challenges. Among other things, emergencies reveal personal and organisational grit. For some, emergencies bring out the best and for others, the worst. That said, even if one has excelled at the emergency stage, it is prudent to watch out. Initial momentum rarely lasts. The adventure of crisis management devolves into panic mitigation, making day-to-day business challenges seem insurmountable.

That is what marks the beginning of the second stage — regression. Psychologists tell us that regression is our defense mechanism against confusion and insecurity by creating the illusion of an emotional comfort zone. We feel listless, bicker over trivial matters, mess up our sleep cycles and either forget eating or overindulge. The regression phase is both uncomfortable and unavoidable. The key challenge for anyone in the regression stage is to pull through without the burden of unrealistic expectations, get to the recovery phase and prepare for the new normal.

The regression phase is both uncomfortable and unavoidable. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

The regression phase is both uncomfortable and unavoidable. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

On May 12, the Canadian federal government <47> sent a thoughtful email to all its employees with guidelines on working from home. The most empathetic aspect of that email was that it acknowledged regression as a natural phenomenon and offered constructive suggestions to deal with it.

The first step is to identify the triggers of our regression. The next step is to disrupt status quo. Fresh starts reenergise us, especially if we focus on doing things differently. Subtle nudges and micro changes in habit make all the difference.

The third step includes learning to calibrate the emotions of people we interact with regularly. Simply discussing our scores and sharing our coping mechanisms led to a meaningful conversation about the support needed to negotiate the crisis.

Fresh starts reenergise us, especially if we focus on doing things differently.

The fourth and final step is to go beyond the survival-first instinct <48> and visualise the impact of our work. Wedell-Wedellsborg suggests we rephrase “How can we handle the crisis?” to “How might we emerge from the crisis stronger?” Such reorientation tends to shift our focus from managing short-term risks to working towards our long-term vision.

This four-pronged plan can help us negotiate better with the unavoidable regression that marks every crisis. While regression can be uncomfortable, it can help unburden us from the pressure of unrealistic expectations and reveal new answers that chart the road to recovery.

Panic working in the coronavirus era

Far from slowing down, many of us have pushed ourselves into even more demanding schedules as we grapple with the specter of COVID-19. We feel compelled to conquer the crisis by accomplishing more than we are usually satisfied with. Gianpiero Petriglieri, professor of organisational behaviour at the INSEAD Business School, calls it “panic working.” <49>

Working extra hard provides an illusion of control in times of crises when things are falling apart. Obsessive work and hyper-productivity also offer a false sense of comfort. It is a defense mechanism where we desperately try and hold on to the world we once knew. Indirectly, we are trying to prolong our denial and work ourselves into numbness.

Obsessive work and hyper-productivity offer a false sense of comfort. It is a defense mechanism where we desperately try and hold on to the world we once knew.

Although panic working temporarily shields us from feeling out of control, it comes at a high price. We lose our ability to experience things as they are and connect with people. In other words, we subdue our empathy and compassion to create a false sense of order in our lives. During times of crises we need to focus on helping others, figuring out what our community members need, and attempting to make a difference to their lives. Health workers were hailed as the heroes of the COVID-19 crisis because they worked relentlessly to keep others safe.

While health workers spent many more hours at work, it is not what Petriglieri calls panic working. They worked to address our panic and they are, perhaps, doing the most meaningful and most professionally satisfying work of their career. Therein, lies an important lesson for us — in times of crises, it helps to shift focus from our own suffering to that of others. By doing so we not only make a difference, but we also end up doing some of our best work.

Based on a survey conducted on Network Capital, about 70 percent of the 940 responders <50> said that they were working more under the COVID-19-induced lockdown. Not everyone who is working more than usual is panic working, but it is easy to slip into the denial mode where we go on hustling pretending nothing happened.

It is perhaps time to be kind to yourself and accept that these are extraordinary times.

If you identify as someone who is panic working through the crisis, it might be time to take a short pause to reflect on what matters to you and why. You do not necessarily need to prove to yourself or the world that you outworked the virus. It is perhaps time to be kind to yourself and accept that these are extraordinary times. Disorientation, agitation and anxiety are natural byproducts. These feelings cannot be swept under the rug by beating self-imposed deadlines and accomplishing challenging professional goals.

Crises tend to crack us open and reveal who we are to our own selves. This crisis will be etched in our memories long after we have found its cure but what we will remember the most is how we felt, what we did and who we served.

Putting it all together

Voltaire said that work spares us from three evils — boredom, vice and need. The current pandemic puts things in perspective. Work has never only been about a pay cheque but in the post-pandemic world, it is sure to alter the alchemy of relationships at scale as people will need to keep purpose and insurance constantly at the back of their minds while making professional choices.

The ‘fittest’ will survive but who will take care of the most marginalised? Those who crumbled under the COVID-19 crisis but could not bounce back?

As we think of the future of modern, remote-first workplaces, we are likely to witness new business models. Leisure will be redefined and hopefully a healthier conversation about mental health would take place.

The ‘fittest’ will survive but who will take care of the most marginalised? Those who crumbled under the COVID-19 crisis but could not bounce back? Employment figures often gloss over such uncomfortable subjects, but we cannot afford to push them under the rug for too long. A combination of emotional resilience training and practical hands-on skill building will be required. There are, however, several unanswered questions: Who will pay for it? How will this be delivered? How will you measure success? Whose responsibility is it anyway?

As we grapple with these questions, we must strive to make diversity and inclusion integral to business strategies and business models of the future. A semblance of equity is surely worth working towards.

Endnotes

<1> Kiran Pandey, “COVID-19: 400 mln jobs lost in Q2 2020, says ILO”, Down To Earth. July 02, 2020.

<2> Shwweta Punj, “Down, but not out”, India Today, August 01, 2020.

<3> Punj, Down but not Out

<4> Punj, Down but not Out

<5> Punj, Down but not Out

<6> Anne Field, “For ConBody’s Founder, Success Means Hiring More Ex-Offenders Like Himself”, Forbes, March 29, 2018.

<7> Li Jin, “The Passion Economy and the Future of Work”, Andreessen Horowitz Report, October 08, 2019.

<8> NPR, “Dave’s Killer Bread: Dave Dahl”, NPR. July 01, 2019.

<9> Li Jin, “Enterprization of Consumer”, Li Jin, September 06, 2019.

<10> “Pasta Grannies”

<11> Punj, Down but not Out

<12> Paul Jarvis, “An excerpt from Company of One”, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

<13> Y Combinator, “Competition is for Losers with Peter Thiel (How to Start a Startup 2014: 5)”, YouTube. 50:27, March 22, 2017.

<14> Strachery, “Daily update”, Strachery, 2020.

<15> Andreas Stegmann, “Ben Thompson’s Stratechery should be crossing $3 Million profits his year”, Medium, May 19, 2020.

<16> Stegmann, Ben Thompson’s Stratechery should be crossing $3 Million profits his year

<17> Matt Mullenweg, “Why working from home is good for business”, Ted, 04:27, January 2019.

<18> Nicholas Bloom et al., “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment”, The National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2013.

<19> Bloom et al., Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment

<20> Matt Mullenweg, “Why working from home is good for business”, Ted, 04:27, January 2019.

<21> Dan Ascher, “Coronavirus: ‘Mums do most childcare and chores in lockdown”, BBC, May 27, 2020.

<22> Ashcher, Coronavirus: ‘Mums do most childcare and chores in lockdown

<23> “Herminia Ibarra”, Harvard Business Review.

<24> “Julia Gillard”, Harvard Business Review.

<25> “Tomas Chamorro Premuzic”, Harvard Business Review.

<26> Herminia Ibarra et al., “Why WFH Isn’t Necessarily Good for Women”, Harvard Business Review, July 16, 2020.

<27> Jack Kelly, “Companies In Their Cost Cutting Are Discriminating Against Older Workers”, Forbes, August 03, 2020.

<28> Caroline Kitchener, “’I had to choose being a mother’: With no child care or summer camps, women are being edged out of the workforce”, The Lily, May 22, 2020.

<29> Herminia Ibarra et al., Why WFH Isn’t Necessarily Good for Women

<30> Pablo Uchoa, “Coronavirus: Will women have to work harder after the pandemic?”, BBC, July 14, 2020.

<31> Uchoa, Coronavirus: Will women have to work harder after the pandemic?

<32> Alison Reynolds and David Lewis, “Teams Solve Problems Faster When They’re More Cognitively Diverse”, Harvard Business Review, March 30, 2017.

<33> “Gender pay gap statistics”, Eurostat, February 2020.

<34> Lianna Brinded, “It’s going to take 217 years to close the global economic gender gap”, Quartz, November 02, 2017.

<35> Janeen Baxter and Erin Olin Wright, “THE GLASS CEILING HYPOTHESIS: A Comparative Study of the United States, Sweden, and Australia”, Sage Journals, April 1, 2000.

<36> Dave Smith, “Most People Have No Idea Whether They’re Paid Fairly”, Harvard Business Review, December 2015.

<37> Smith, Most People Have No Idea Whether They’re Paid Fairly

<38> “Morten Bennedsen”, INSEAD.

<39> “Wage transparency works: Reduces gender pay gap by 7 percent”, INSEAD, December 6, 2018.

<40> Zamil Jaki, “The War for Kindness”, Broadway Books, June 2, 2020.

<41> Jaki, The War for Kindness

<42> Melissa De Witte, “Stanfordscholar examines how to build empathy in an unjust world”, Stanford News, June 5, 2020.

<43> William Roberts, “Children’s Personal Distance and Their Empathy: Indices of Interpersonal Closeness”, International Journal of Behavioral Development, February 3, 2010.

<44> Melissa De Witte, “Instead of Social Distancing, practice “distant socializing” instead, urges Stanford psychologist”, Stanford News, March 19, 2020.

<45> Maithe Chini, “Belgians follow Italy’s example and sing against coronavirus”, Brussels Times, March 17, 2020.

<46> “How to Handle a Crisis”, Dr. Merete Wedell-Wedellsbord.

<47> “Mental health and COVID-19 for public servants: Protect your mental health”, Government of Canada, August 8, 2020.

<48> Merete Wedell-Wedellsbord, “If You Feel Like You’re Regressing, You’re Not Alone”, Harvard Business Review, May 22, 2020.

<49> Gianpiero Petriglieri, “Why Are You Panic-Working? Try This Instead”, Bloomberg Opinion, March 24, 2020.

<50> “Network Capital”, Network Capital TV.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

People will need the discipline and the rigour to work hard, experiment fast and deliver consistently. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

People will need the discipline and the rigour to work hard, experiment fast and deliver consistently. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

Mothers are doing, on average, more childcare and more housework than fathers who have the same work arrangements. Illustration: Monica Rief/Getty

Mothers are doing, on average, more childcare and more housework than fathers who have the same work arrangements. Illustration: Monica Rief/Getty The regression phase is both uncomfortable and unavoidable. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty

The regression phase is both uncomfortable and unavoidable. Illustration: Malte Mueller/Getty PREV

PREV