This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

The Energy Conservation (Amendment) Act was passed by the lower house of the Indian parliament in August 2022. The act is designed to amend the Energy Conservation Act, 2001 and the revised provisions have been welcomed by most stakeholders and consumers. Climate activists see the provision that enables the central government to impose the use of non-fossil fuels on energy consumers as an important provision that will help India

meet its climate goals. The amendment that allows the central government to implement a carbon trading scheme is generally seen as positive, but some observe that it is ambiguous. Climate advocates have also welcomed powers conferred on the central government to mandate

energy conservation standards for buildings, appliances, and vehicles. The amendment that empowers the

state electricity regulatory commissions (SERCs) to adjudge penalties and to make regulations for discharging their functions has offered some comfort to the concern that the central government is appropriating powers of state governments over regulations on electricity. The expansion of the governing council of the

bureau of energy efficiency (BEE) under the act to include members from six ministries, departments, regulatory institutions and members from industries and consumer groups was welcomed by most stakeholders.

Energy Conservation, Energy Intensity and Carbon Intensity

Energy conservation is often used

interchangeably with energy efficiency. Though they are closely connected, they are not the same. Energy conservation means

using less energy (such as turning off the lights when leaving the room) whilst efficiency means using energy wisely (using light emitting diode (LED) lamps instead of fluorescent lamps to get the same amount of lighting). Energy conservation

improves the energy use efficiency of existing energy capital stock. This often means technological change using substantial capital investments through which

new technologies diffuse into the capital stock (such as incorporating a sensor device that automatically turns off the light when there is no one in the room). Such

diffusion requires either expansion or replacement investment. Expansion investment, by definition, expanded the existing capital stock (such as investment in new power generation capacity), enabling increased production levels and increased total energy use, but at a

lower level of energy intensity, assuming new capital is more efficient than existing capital. Replacement investment directly replaces retired capital and includes the investment spent on retrofitted capital (such as replacing existing fluorescent lamps with LED lamps). Consequently,

replacement investment does not expand the capital stock. It does not increase total energy use but enables a faster decrease in energy intensity than does expansion investment, assuming new capital is more efficient than old capital.

Expansion investment, by definition, expanded the existing capital stock (such as investment in new power generation capacity), enabling increased production levels and increased total energy use, but at a lower level of energy intensity, assuming new capital is more efficient than existing capital.

Energy intensity is a measure to assess the energy efficiency of a particular economy. It is calculated by taking the ratio of energy use (or energy supply) to gross domestic product (GDP), indicating how well the economy converts energy into monetary output. The smaller the energy intensity ratio is, the lower the energy intensity of a particular nation. Low energy intensity represents the efficient use of energy to generate wealth.

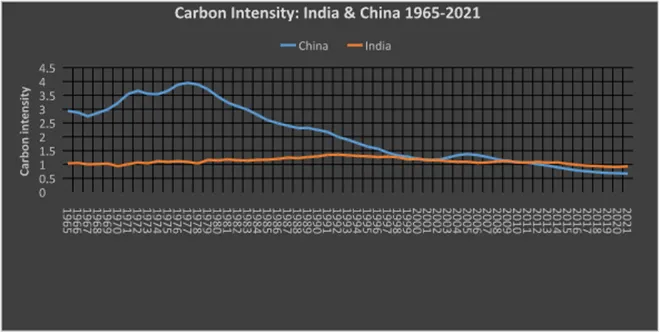

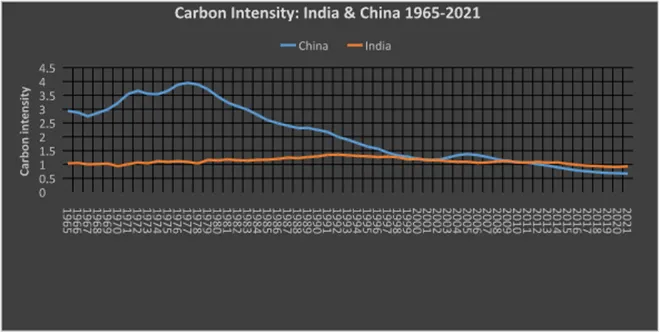

Carbon intensity is the carbon emission per unit of energy consumed, which reflects the energy mix used to produce wealth. Low carbon intensity signals either low energy consumption (as in the case of poor households/regions/countries) or an economy that consists of high efficiency in energy use or the dominance of low energy activities such as services).

In the light of the above, key provisions of the amended act, barring the power given to the central government to mandate energy efficiency standards on devices, focus on reducing carbon intensity rather than on energy conservation or energy efficiency. Essentially, the energy conservation amendment act is used as a vehicle to meet India’s commitment to reduce the carbon emissions intensity of its GDP (gross domestic product) by

45 percent by 2030, from the 2005 level and achieve about 50 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030 as communicated in its

updated nationally determined contribution (NDC).

Trends in India’s Carbon Intensity

Between 1970-90, commercial energy consumption in India grew at an average of 5.7 percent whilst the economy grew at an average of about 4.3 percent. In this period, a

substantial increase in infrastructure building, especially for power generation, increased industrial energy consumption; investment in electrical equipment and motor cars increased middle-class household electricity, petroleum, and gas consumption. These developments contributed to an increase in CO

2 emission intensity, but since the early 1990s when India partially opened its economy, India’s CO

2 emission intensity has shown a declining trend. This was mainly driven by a decrease in energy intensity.

Structural shift away from traditional biomass (firewood, animal dung etc.) as fuel for cooking in Indian households was one of the key drivers of the increase in energy use efficiency.

Between 1990 and 2019, India’s

GDP increased more than six-fold, whilst total final energy consumption increased only by a factor of 2.5 (or

GDP grew more than twice as fast as energy consumption). This means that India has required less energy to produce an additional unit of economic output over the years. According to government data, India’s CO

2 intensity in

2021 was 28 percent lower than the CO2 intensity in 2005. Structural shift away from traditional biomass (firewood, animal dung etc.) as fuel for cooking in Indian households was one of the key drivers of the increase in energy use efficiency. Although millions of Indian households continue to use biomass as their primary fuel for cooking, the share of energy derived from biomass in final energy consumption fell from

42 percent in 1990 to 18 percent in 2019 as households shifted to LPG (liquid petroleum gas) or piped natural gas. The switch from biomass with a very low conversion efficiency (5-10 percent) to high efficiency petroleum-based fuels enabled economic activity growth without commensurate growth in energy consumption. The decline in the share of biomass in India’s energy basket was responsible for

60 percent of the decline in energy intensity.

The second driver of improvement in energy intensity was the shift in the structural composition of growth in favour of the services sector, which is less energy intensive than growth dominated by industry. Nearly

90 percent of total value‐added growth in India in the period 1990‐2017 came from sectors in the lowest energy intensity category, including large retail service sectors, business, and financial services. The third driver of the improvement in energy intensity in India was

technical efficiency of production and consumption processes. Relatively high energy prices, price sensitivity amongst consumers, and a young capital stock contributed to

technical efficiency in energy use. The general wave of economic efficiency improvements that occurred after liberalisation in the early 1990s also contributed to the improvement in technical efficiency in manufacturing processes in India.

Divided equally between a population of over 1.395 billion, it amounts to a per person electricity consumption of just under 1000 kilowatt hours (kWh) which is lower than the world average of 3316 kWh in 2020.

The fourth factor, a rather perverse one, is India’s slow pace of industrialisation and the consequent

low per person energy consumption that has a limited energy intensity and carbon intensity. In 2019-20 (pre-covid), India generated

1381 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity. Divided equally between a population of over 1.395 billion, it amounts to a per person electricity consumption of just under 1000 kilowatt hours (kWh) which is lower than the world average of 3316 kWh in 2020. India is the only country in the G20 group that has energy consumption below the world average. Low energy consumption, or more accurately, low incomes that limit energy consumption at the household level, has meant poor quality of life for millions of households, especially in rural India. This, in turn, has contributed to lower energy and carbon intensity.

Challenges

The new provisions introduced in the energy conservation amendment act aim to facilitate the substitution of fossil fuels with renewables at the supply end though this is not consistent with the concept of energy conservation. As the

factors that have so far contributed to lowering energy intensity and consequently reducing carbon intensity (shift away from biomass to modern cooking fuels, shift away from manufacturing to services, gains in industrial energy efficiency, and low per person energy consumption) are unlikely to continue, increase in the share of non-fossil fuels at the expense of fossil fuels becomes important to reduce carbon emission intensity. However, India’s decarbonisation goals are

not necessarily consistent with its industrial policies such as “make in India” and “self-reliance”. Development of an industrial base at this late stage, even if it is for the manufacture of climate-friendly goods, may increase energy intensity, countering the effort to reduce carbon intensity.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV