In India, a prime factor for the slowdown in the solar photovoltaics (PV) sector in 2018 was the implementation of the safeguard duty on imported solar panels. While imposition of this duty was aimed at incentivising domestic manufacturing, it led to an increase in tariffs, resulting in the cancellation of many solar auctions and their retendering. This slowdown might be temporary, since long-term trends like falling cost of photovoltaic (PV) modules do remain in place. The growth in India’s solar capacity has been driven mainly by imported PV modules that enjoy

nearly 90 percent share, as their costs are up to

30 percent lower. The safeguard duty was pegged by the government at

70 percent on foreign modules, but was introduced at

25 percent owing to pressure from energy companies.

The Solar Energy Corporation of India Ltd. (SECI), a company run under India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, made an effort in May 2018 to boost local manufacturing by bringing out a

tender for setting up 10 GW of solar power projects linked with 5GW per annum domestic solar manufacturing capacity. A poor response from the industry resulted in multiple

extensions of the deadline for this tender. The tender capacity for manufacturing was later

reduced to 3GW, where the developers were to be provided guaranteed Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) of two GW for a manufacturing capacity of 600 MW. The total power projects awarded would thus have remained at 10 GW.

In January 2019, government announced its plan to cancel the previous tender and float a new manufacturing-linked solar tender. SECI then issued a

tender for 3GW of grid-connected solar capacity linked with 1.5 GW of manufacturing capacity. The minimum capacity for bidding will be 1,000 MW of solar capacity linked with 500 MW of solar manufacturing, both to be developed on build-own-operate basis. SECI will enter into a 25 year PPA with a maximum payable tariff at INR 2.75 per unit. This tender too is likely to be cancelled due to tepid response. Such incidences of issuing and modifying tenders and eventually cancelling them, clearly showcases the difficulties faced by India’s solar PV manufacturing sector.

The government and the industry had several rounds of discussion on this model but project developers are apprehensive to venture into the manufacturing business. Both have found it difficult to arrive at a suitable electricity tariff cap. The tumultuousness in the Indian economy such as rupee depreciation, rising interest rates, changes in GST, etc. led to setting of tariffs where industry felt the bids became financially unviable with little room for profit margins.

Additionally the solar manufacturing industry faces the danger of the fast-changing technology. The off-take commitment of two years, as per the latest SECI tender, from the government was also too ambitious, since, the industry may take at least five years to match efficiency of Chinese manufacturers, who have undergone the learning curve to mass produce solar PV components. Also, the industry fears that there is no protection from imports from China in future years where costs are already declining rapidly. Some experts have claimed that the government’s approach of making Indian project developers enter the manufacturing business it not the right way ahead. The key

argument here relates to financing of such a model where manufacturing needs high equity and low lending whereas project generation needs low equity and high lending which may not work together.

In another development in February 2019, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) approved a viability gap funding scheme worth

INR 8,580 crore, which would enable government-owned companies to set up 12 GW of solar power plants over the next four years using the made-in-India modules, which are costlier. The scheme is supposed to attract a total investment of

INR 48,000 crores and create around

200,000 jobs. Since most manufacturing plants in India still run on old technology, these funds may end up being spent inefficiently. Also, there are still questions on the WTO-compliance of this scheme post India losing it case at the WTO due to its ‘domestic content requirement (DCR)’ rule.

India has about

3 GW of cell and nine GW of module manufacturing capacity. Only 1.5 GW and 3GW of it, respectively, are actively in use. To be in line with the ‘Make in India’ initiative, there is an urgent need for technological upgrade of these plants, which currently employ old technology, for being competitive. But, for Indian manufacturers, protection from the safeguard duty soon disappeared since Chinese panel manufacturers also reduced the module prices. China’s curtailment of its solar growth from mid-2018, was the primary reason for the Chinese panel manufacturers to cut module prices by up to

35 percent. Hence, there is no real incentive for Indian manufacturers to start running their plants at full capacity.

A thrust for domestic supply of panels surely gives assurance that developers can get modules at a certain price as there are less variables (e.g. foreign exchange rates) in procurement and gives comfort to both parties with no difficulties around import logistics. This proposed Viability Gap Funding (VGF) scheme for Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs), with an assured market for four years, is expected to instill confidence in Indian manufacturers to face future competition.

A 25 percent capital subsidy for solar manufacturing units is available under the ‘

Modified Special Incentives Package Scheme’ (M-SIPS). However, this has not attracted investments from domestic solar manufacturers. Given the outdated technology employed by Indian manufacturers, there is a need for investments in R&D to establish state-of-the-art manufacturing units. Many businesses will like to test the waters by setting up smaller plants at the initial stages before making big investments. The lending interest rates in China and Japan are way lower than those in India, which, becomes a hurdle to attract investments in manufacturing. India needs to learn from

China’s Top Runner policy which focuses on new technology and efficiency over price whereas India is more focussed on low tariffs.

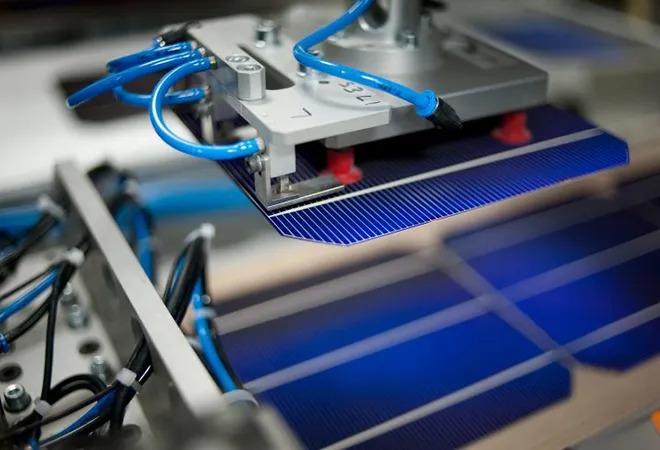

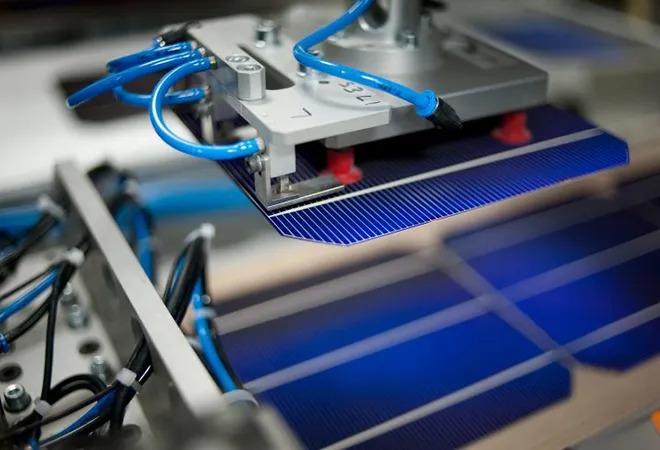

It is a daunting task for developers to undertake manufacturing as it asks for integration of the present value chain in solar PV. Manufacturing solar modules involves processing sand to make silicon (mono or poly), casting silicon ingots, making wafers from ingots, using wafers to create cells and then assembling them to make modules. Currently, the Indian PV manufacturing industry produce only cells and modules, except for a couple who make wafers. Setting up a holistic integrated manufacturing hub (silicon to modules) needs high capital expenditure and demands considerable power and water supply. Such business will require special incentives through tax waivers to attract investors. Many Chinese players are still evaluating this sector in India due to doubts around the financial viability of such plants.

There is a need for a better ecosystem to be provided by the Indian government to boost local solar PV manufacturing through provision of right infrastructure and incentives rather than protectionist measures like safeguard duty. A SEZ that focuses only on integrated module manufacturing could be planned to create a conducive environment. The gestation time for setting up manufacturing facilities including land and allied activity will take a minimum of two years, which the government needs to keep in mind before framing policies with certain deadlines. There will also be a need for India to steadily move towards higher efficiency panels and newer technologies which will help realise the overall cost advantage in terms of balance of system and land cost of projects. A right policy framework with well-defined objectives will help India set up a robust PV manufacturing ecosystem.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

In India, a prime factor for the slowdown in the solar photovoltaics (PV) sector in 2018 was the implementation of the safeguard duty on imported solar panels. While imposition of this duty was aimed at incentivising domestic manufacturing, it led to an increase in tariffs, resulting in the cancellation of many solar auctions and their retendering. This slowdown might be temporary, since long-term trends like falling cost of photovoltaic (PV) modules do remain in place. The growth in India’s solar capacity has been driven mainly by imported PV modules that enjoy

In India, a prime factor for the slowdown in the solar photovoltaics (PV) sector in 2018 was the implementation of the safeguard duty on imported solar panels. While imposition of this duty was aimed at incentivising domestic manufacturing, it led to an increase in tariffs, resulting in the cancellation of many solar auctions and their retendering. This slowdown might be temporary, since long-term trends like falling cost of photovoltaic (PV) modules do remain in place. The growth in India’s solar capacity has been driven mainly by imported PV modules that enjoy  PREV

PREV