This is the 81st article in the series

This is the 81st article in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles here.

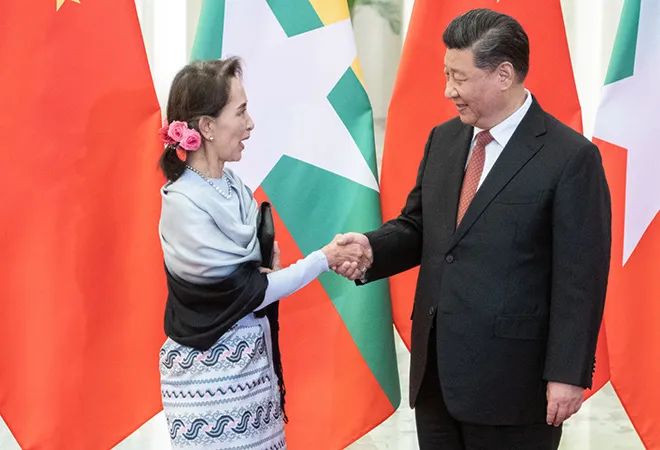

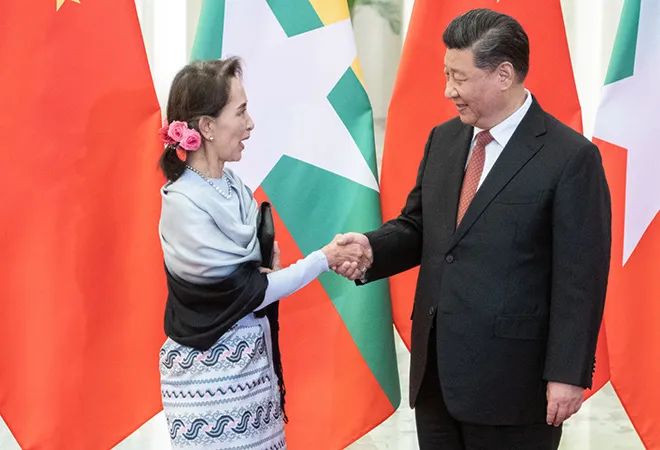

At the second Chinese Belt and Road Forum (BRF) attended by Myanmar’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi in April 2019, three MoUs were signed to strengthen cooperation on the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) integral to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This was the latest in a series of MoUs reached between China and Myanmar on the CMEC in recent years.

Myanmar’s increasing dependence on China in dealing with internal and external challenges and Beijing’s ability to leverage Naypyidaw’s strategic compulsions to its advantage has been a defining featuring of the current bilateral relationship. China has been extending political and financial support to the Myanmar government in managing the country’s ethnic conflicts along their shared borderlands and protecting it at the United Nations for atrocities against the Rohingyas.

China-Myanmar relations entered a difficult phase soon after Myanmar initiated political reforms in 2011. Suspension of the Chinese-backed Myitsone dam and outflow of refugees into China as ethnic conflicts intensified along China-Myanmar borders sparking tensions between the two countries. Concerns over increased involvement of Western countries in Myanmar’s ethnic peace process in the following years and the desire to push forward the BRI motivated Beijing to improve ties with the Myanmar government.

Subsequently, relations improved when Aung Sun Suu Kyi’s party the National League for Democracy (NLD) came to power in early 2016. This coincided with increasing international condemnation of Myanmar over the handling of the Rohingya crisis, particularly after August 2017. China aligned itself with the Myanmar government’s interests on the Rohingya crisis and the ethnic peace process. This allowed Beijing to minimise the role of other external players, on the one hand and obtain strategic projects in Myanmar, on the other.

China and Myanmar signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on cooperation within “the Framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative” in May 2017 when Aung San Suu Kyi attended the first Chinese BRF. Five months later, the CMEC was proposed and an official agreement on the “Y-shaped” corridor was signed September 2018 to connect China’s Kunming to Mandalay and then extending east and west respectively to Yangon and Kyaukpyu.

In March 2018, another MoU was signed to conduct feasibility studies for the construction of the Mandalay-Tigyaing-Muse expressway project and Kyaukpyu-Naypyidaw highway project. There was not mention of these projects being part of the BRI at the time of signing the MoU, but now seen as part of the CMEC. In July 2018, Myanmar approved three economic cooperation zones along the Myanmar-China border–––one is Kachin State and second in Shan State. Earlier, the agreement to establish the border trade zones as part of the BRI was reached in 2016 and MoUs signed in May 2017.

In August 2018, Myanmar renegotiated the Kyaukpyu deep-seaport. The US$ 7.3 billion project was agreed in 2015 between the previous Thein Sein government and Chinese state-owned Citic Group. However, the Myanmar government decided to scale-down the project to a US$ 1.3 billion deal, with just two jetties, which could be expanded later if required.

Furthermore, the China-Myanmar high-speed railway project or the Kunming-Kyaukpyu Railway (abandoned in 2014) was revived when the two countries signed an MoU in October 2018 to conduct feasibility studies of a railway line linking Muse, with Mandalay in central Myanmar. In November 2018, China and Myanmar held their first science and technology cooperation meeting in Yangon, where they established a joint radar and satellite communications laboratory as part of the CMEC. Myanmar’s Ministry of Transport and Communications has been working with Huawei to introduce 5G network in the country since December 2018.

Moving beyond the question of whether or not to be part of the BRI, the Myanmar government appears to be pursuing a delicate diplomatic balancing act of securing China’s support to take forward the ethnic peace process and protect it in international fora. In return, Myanmar is willing to be part of Chinese BRI projects that it sees are mutually beneficial, but non-binding. Most of the deals reached in the past couple of years are MoUs that have no legal force.

Towards this end, Naypyitaw has also been leveraging the growing geopolitical competition among major powers to hedge against the BRI. In the re-negotiation of the port deal, Myanmar had sought and received help from the US and other countries. A team of American experts helped Myanmar push through “a better deal”. As US-China strategic rivalry intensifies in the region, Myanmar is likely to leverage the competition to its advantage.

Myanmar has been benefiting from alternative infrastructure development initiatives. Tokyo and New Delhi have been involved in key port, railway and highway projects in Myanmar and have been collaborating in regional connectivity. Strengthening the involvement of more players in the country’s infrastructure development without inviting Beijing’s ire would be a challenge going forward.

Internally, the growing opposition to Chinese mega-projects in the country means Myanmar’s political leadership would need to deal with China’s pressures without compromising its domestic political legitimacy. Just before Aung San Suu Kyi’s visited China last month, there was a massive protest against the Chinese-backed Myitsone dam in Myanmar. The growing unpopularity of the Myitsone dam project may push the Myanmar leadership with no other option than to abandon the project, in exchange for guarantees to the CMEC projects. Strategically the CMEC is far more critical to China and both sides may consider such possibilities as a way out.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s speech at the BRF indicate a desire on the part of the Myanmar leadership to reflect the concerns of the Myanmar people. The BRI projects should “not only be economically feasible but also socially and environmentally responsible, and most importantly, the projects must win the confidence and support of local people”, she said. With general elections scheduled next year, Myanmar’s political leaders will increasingly seek to minimise the alienation of the people and relations with China assessed accordingly.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This is the 81st article in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles

This is the 81st article in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles  PREV

PREV