In the first six months of 2019, two protest campaigns in Russia garnered widespread attention, owing to their unexpected success. The first was the campaign to save a park in Yekaterinburg being threatened due to a proposed church at the site. The other was the arrest of investigative journalist Ivan Golunov in Moscow on trumped up drug-charges that were subsequently dropped following a mass outcry and a rare solidarity among media houses. Less publicised was the resignation of Ingushetia’s governor Yunus-bek Yevkurov after protests over an unpopular land-swap agreement with Chechnya.

The fact that these victories came about as a result of popular action is not a common development for Russians. Earlier in 2018, protests against pollution from overflowing landfills in Moscow region led to their closure. This led to further protests in 26 regions selected to be new sites for the waste disposal due to concerns about the environmental impact. While in some cases the local governments have backtracked (Arkhangelsk), others are proceeding as planned.

It is difficult to discern a pattern in popular protests leading to concessions from the government.

Despite widespread protests, the pension reforms announced in June 2018 raising the retirement age from 60 to 65 for men and from 55 to 63 for women, it was signed into a law (President Putin did lower age for women to 60). Thus, looking at these disparate cases, it is difficult to discern a pattern in popular protests leading to concessions from the government.

The emerging trend

In the past couple of years, as per two Moscow-based organisations, the focus of majority of protests across Russia has been on socioeconomic issues. After the crackdown on politically charged protests of 2011-12, “civic activists retreated to local and socioeconomic issues.” This coincided with a sustained period of economic stagnation worsened by western economic sanctions. The fall in real disposable incomes is now into its sixth year leading to a declining standard of life.

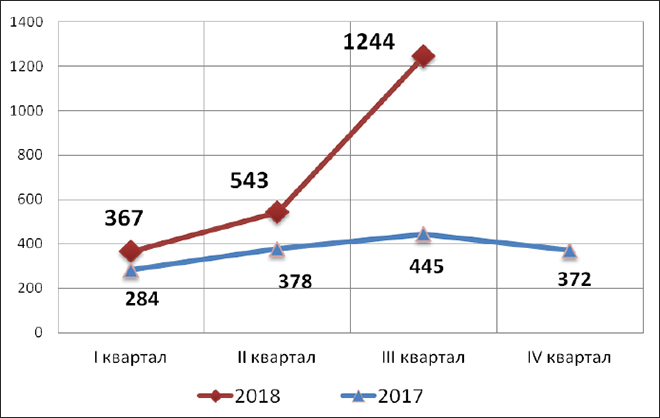

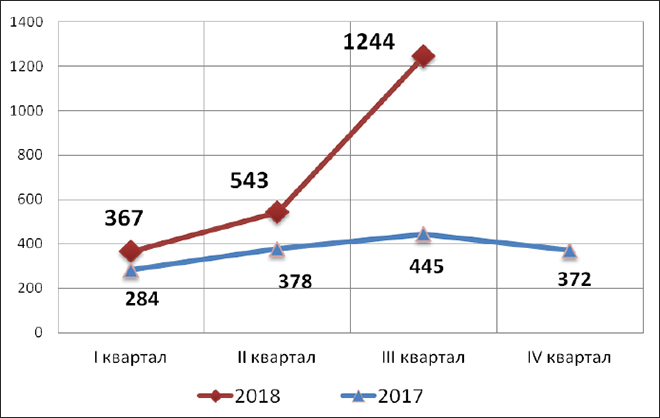

Out of 2,526 protests analysed by the Centre for Economic and Political Reform (CEPR) from October 2017 to September 2018, 74% were related to socioeconomic problems while only 16.4% were of a political character. There was a sharp rise in the total number of protests in the third quarter after the announcement of pension reforms in June 2018. The number of protests in previous quarter were 543, from which it rose more than twice to reach 1,244. This indicates that the people are willing to focus on specific issues that affect them directly in the economic domain.

Source: CEPR

Source: CEPR

The data available from Centre for Social and Labour Rights also confirms the pattern despite a slight difference in total numbers. According to it, after the announcement of the pension reforms, protests increased 1.6 times from 493 in the second quarter of 2018 to 834 in the next. Out of 429 protests from Jan-Mar 2019, 157 were related to social issues including rise in tariffs for garbage collection, pension reforms, reduction of benefits, rise in transport tariffs etc. The protests on these issues increased from 86 in Jan-Mar 2018 to 157 in Jan-Mar 2019. On the other hand, in the same period, political and civil protests came down from 149 to 108.

People are willing to focus on specific issues that affect them directly in the economic domain.

There is a rise in willingness among the Russians to protest, and 28% of population is ready to participate on issues related to falling living standards while on political issues it is at 23%. This follows a continued decline in living standards, especially in the regions away from the capital centre, evident in highest number of social protests being witnessed in the eastern regions like Yakutia, Khabarovsky Krai, Sakhalin and Primorskii Krai. In Khabarovsk, in the elections to the post of governor after the announcement of pension reforms, the United Russia (UR) candidate was defeated through popular vote. The ratings of UR have been declining steadily and the population willing to vote for it has declined from 63% in June 2016 to 33.9% in June 2019.

This also prompted a reshuffle of the governors before the gubernatorial elections in 2018 and 2019 as the Kremlin introduced new candidates to stave-off anti-incumbency. As a result, in the 2018 regional elections, UR managed to win 21 out of 26 seats. It won even in regions with high protest activity like Krasnodar, Moscow, Samara, Altai, Novosibirsk, Tyumen etc. In contrast, in several regions that top the number/turnout of protests, the regional leadership still stands.

Also, while falling ratings, lack of public support and conflicts with the regional elite have been ascribed to the changes of regional leadership, it does not always coincide with the protest activity in the region. The table lists some regions whose leaders were removed by the Kremlin alongside the rating based on total protests/size (2017-18), from which a direct relationship between the number of protests/size leading to leadership change cannot be discerned. This is in addition to uncertainty over Kremlin’s reaction to protests.

|

2019

|

Top 10 regions with largest protests (over 1,000 people) |

Rating by number of protests |

| Chelyabinsk |

2 |

7 |

| Murmansk |

— |

59 |

| Kalmykia |

— |

78 |

| Altai |

6 |

14 |

| Orenburg |

8 |

6 |

| Ingushetia |

— |

81 |

| 2018 |

|

|

| Bashkortostan |

— |

33 |

| Kursk |

— |

39 |

| Primorye |

— |

12 |

| Astrakhan |

— |

26 |

| Kabardino-Balkaria |

— |

75 |

| Lipetsk |

— |

72 |

| Kurgan |

— |

39 |

| Arkhangelsk |

— |

58 |

| St Petersburg |

4 |

3 |

Source: CEPR

Effectiveness of protests

Due to the factors mentioned above, protests have not been a reliable indicator of political change in Russia. The small-scale nature of protests (60.4% up to 100 people, 27.4% 100-500 people) also blunts their impact. Even the 2017 anti-corruption protests that saw a turnout of 35,000 in Moscow constituted less than one-fifth of 1% of its total population.

36.2% of the protests in 2017-18 were organised by CPRF while opposition leader Alexei Navalny was next with 13.1% but has not translated into significant electoral gains for them. CPRF did defeat a UR candidate in gubernatorial elections held in 2018 after the pension reform was organised (Khakassia) and led to a run-off in Primorskii Krai (eventually won by UR). While the former region is at a lower position in its rating based on total number of protests, the latter stands at 12th position in this regard, positing no clear relationship between the number of protests and change of regional leadership. The same is the case with LDPR victories.

|

Rating in largest protests action (over 1,000 people) — Top 10 |

Rating by number of protest actions |

Winning party |

| Khabarovsk |

— |

19 |

LDPR |

| Vladimir |

— |

41 |

LDPR |

| Khakassia |

— |

42 |

CPRF |

Source: CEPR

It remains unclear as to what would lead the government to concede to the demands of the protestors, though it is evident that political demands are put down more stringently as compared to those related to social issues. Some protests are used to shore up the image of the president (who has the approval rating of 65.8 per cent) to show him as intervening in the favour of the regional populations, which forms the bulk of his supporters. The intermittent removal of regional governors is another way for the government to appease the population and increase support for Putin.

The fact that most of the protests are local, concentrated in a specific area, and lack the ability to capture national attention for popular mobilisation — their capacity for political upheaval at the top remains limited at the moment.

Apart from the June 2019 protests in Moscow calling for independent candidates to be allowed on the ballot for city legislature elections, significant number of protests are not political in nature. They aren’t led by a single leader to push for political change but focus on concrete social problems related to the standard of living and are not very well organised. Add to this the fact that most of the protests are local, concentrated in a specific area, and lack the ability to capture national attention for popular mobilisation — their capacity for political upheaval at the top remains limited at the moment.

Conclusion

Since Vladimir Putin came to power, there has been a tacit social contract — non-engagement in political activity by citizens in return for economic prosperity. Now that the government is struggling to deliver on its economic promises, that contract is in peril. This can be seen in rise in number of protests with a socioeconomic component and a decline in the president’s trust ratings since 2018 pension reforms. Most recently, it has led members of UR party to stand as independents in the upcoming Moscow City Duma elections, a tactic it has used earlier to get around unpopularity.

This is also indicative of shift in the popularity of the nationalist rhetoric after the annexation of Crimea. There is also a demand from the people to be treated with dignity. However, the strict control maintained by the Kremlin over the political parties, electoral process and the media, the consequences attached with unsanctioned protests, weakness of the systemic and non-systemic opposition remain critical barriers in ensuring an electoral defeat of the ruling party.

As a result, varied protests have not coalesced into a sustained challenge for those in power in Russia. It remains to be seen how this control will be exercised as the constitutionally legal term for Putin draws to an end in 2024 and whether the ensuing uncertainty will be the impetus to lead to political change.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: CEPR

Source: CEPR PREV

PREV