On 25 September, the Supreme Court of India delivered a major judgment directing the Election Commission (EC) to take immediate measures to address the rising criminality in the country’s politics. Highlighting the importance of full disclosure to public, a five-judge Constitution bench, headed by Chief Justice Dipak Mishra, observed that the voters should have all information about antecedents of their candidates so as to be able to make an informed and competent choice while exercising their voting rights. The court was responding to the petition filed by a well-known democracy watchdog, The Public Interest Foundation, requesting the highest court to debar candidates facing serious criminal charges from contesting elections.

The major highlight of this important judgment was its five directives to the Election Commission of India. These were: (1) A candidate must fill in the prescribed form. (2) The candidate must fill in bold letters that he is implicated in some crime. (3) The candidate must inform his party that he is implicated in some crime (4) On receiving information from a candidate of his criminal antecedents, the party must put this information on its website. (5) The criminal antecedents should be published by the candidate and his party in newspapers, which are widely circulated in the locality. In short, the 100-page judgment by the SC explicitly cited its concern over the sufferance of Indian democracy because of ‘unsettlingly increasing trend of criminalisation of politics’.

The key takeaway of the judgment was the court urging the legislative branch to frame a ‘strong’ law that would make it obligatory for political parties to remove leaders charged with “heinous and grievous” crimes, such as murder, rape and kidnapping and deny ticket to the offenders. The SC made it clear that it should not be expected to legislate for the Parliament. It observed that rapid criminalisation of the country’s democratic politics cannot be curbed by merely disqualifying tainted legislators. It needs much more, including the “cleansing” political parties. This important judgment has come for heavy flaks from the political analysts and democracy watchdogs for its “prescriptive tone” and “missing historic opportunity” to tackle one of the most serious challenges to democratic politics. Analysts feel that the SC bench that never misses an opportunity to exercise ‘judicial activism’ on all kinds of issues, including corruption, environmental pollution, civil liberties, among others, has taken a tactical safe route to avoid confrontation with the legislative branch. In short, the judgment has aroused a significant debate on the nature and extent of judicial power in India.

A growing marketplace for criminal politicians

The deep nexus of crime and politics has a long history in India, although it has caught the public attention in the recent decades. The famous N.N.Vohra Committee in 1993, set up to unearth crime and politics nexus, had documented the rise of criminal empire with the active support of top politicians and bureaucrats, eroding the rule of law and the legitimacy of democratic governance. While the “very explosive” report was never tabled in the Parliament and has since been kept as a top secret by the Ministry of Home Affairs, in recent years there have been many reports and scholarly works that have documented the phenomenal rise of criminal politicians in the country.

A noteworthy recent work, ‘

When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics’ by Milan Vaishnav, brilliantly documents the paradox of free and fair elections with rampant criminality, why political parties embrace criminal candidates and how average voters in many regions of India make no qualm about a candidate’s criminal antecedents while exercising their franchise. According to the author, while weakening of the National Congress and the rise of marginalised groups in the late 1980s and 1990s enlarged the space for crime and politics, the most critical drivers are the collapse of election finance regime and the weak enforcement of the rule of law in the country that have created the “marketplace for criminal politicians”.

There is staggering evidence to back this worrisome development. An analysis of the declared affidavits by the candidates shows a sharp rise of candidates with serious criminal charges winning the elections. For example, in the last Lok Sabha poll, there are 115 Members of Parliament (MPs) out of the total 536 winners who have serious criminal cases pending against them. This is a 21% rise over the 2009 Lok Sabha poll (see Table 1).

Table 1

|

Total number of MPs scrutinised |

Total no. of winners with declared serious criminal cases |

% of winners with declared serious criminal cases |

| Lok Sabha Election 2014 |

536 |

115 |

21% |

| Lok Sabha Election 2009 |

519 |

86 |

17% |

| Lok Sabha Election 2004 |

514 |

60 |

12% |

What is more noteworthy is that most of these elected members with criminal records are extremely wealthier candidates. For instance, in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, 16 out of 23 winners with cases related to murder/attempt to murder are multi-millionaires. Further, 16 winners with declared cases related to causing communal disharmony have an average asset of about 10 crores. More importantly, the 2014 general elections re-elected 165 MPs who had an average asset growth of Rs. 7.5 crores in 5 years (2009-2014). A significant 43% of re-elected MPs also have declared criminal cases themselves, while 13 MPs (18%) have shown an increase in the number of self-declared criminal cases as compared to the previous elections.

Thus, there is deepening nexus between crime and money power in Indian politics.

Resistance to judicial intervention

All major initiatives against the crime-politics nexus have originated through civil society activism with the tacit support of higher judiciary. In a seminal judgment in the

Union of India vs. Association for Democratic Reforms and another in 2002, the Supreme Court directed for a compulsory disclosure of the candidates’ financial, educational and criminal background while contesting elections

. Expectedly, the court verdict was bitterly opposed by most political parties and the Union Government brought an ordinance to nullify the judgment. However, the court rose to the occasion by striking down the ordinance as unconstitutional.

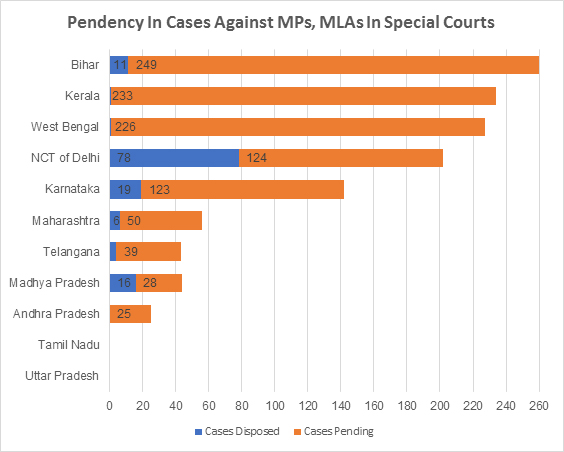

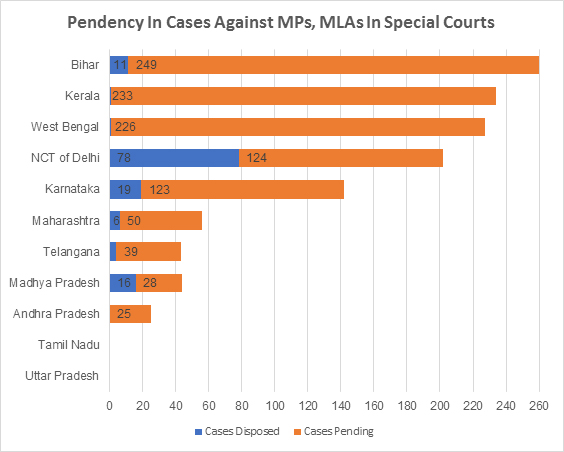

However, this landmark judgment on criminal antecedents did not yield any visible positive outcome as is evident from the rising graph of criminal politicians in last three Lok Sabha polls. The Supreme Court made another valiant attempt to stop the rot in its order on 14 December, 2017. It asked for the setting up of special courts to fast-track the long-pending trials of elected members. Here again, the pace is slow and uninspiring. In an affidavit submitted by the Central Government to the Supreme Court on 11 September this year, the Union Government stated that so far 10 Special Courts have been set up and 1233 cases have been transferred to them. Out of this, however, only 136 cases have been dealt so far. Almost 89% of the cases are still pending. Even in the cases that have been dealt with, the conviction rate is as low as 6%. Expressing its concern over such a slow movement, the Supreme Court again took up the issue on 4 December, pulling up the Centre and the concerned State Governments to speed up the matters regarding the pendency in fast-track courts.

Source:

Source: Centre’s affidavit in Supreme Court (dated 11 September 2018)

Limits of judicial activism

A careful review of the progress on the issue of criminality in Indian politics suggests there is a limit to judicial activism. Similar to other public policy issues, the court-led activism can go up to a point, but not beyond. As illustrated in Milan Vaishnav’s excellent analysis above, there is a tangled relationship between political effectiveness and criminal strength in Indian politics and this cannot be untangled by the courts alone. The buck must stop at the gates of Parliament, and political parties that distribute tickets to candidates with serious criminal records. But given the high ‘winnability’ of such candidates, parties would continue the foot dragging on this vital issue. As behavioral economics teaches, they have “no incentives” to change the current behaviour. Why would legislators do something against their own interests? Further, political parties of all hues, including reformists, would rarely embrace reforms when payoffs for not doing so are much bigger. Yet, with one third of the sitting members having some form of criminal records or other, and when lawbreakers become lawmakers, it is but anybody’s guess what would be its effects on the country’s democracy and the rule of law.

(Niranjan Sahoo is a Senior Fellow and Bhawna Agarwal a Research Intern at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi)

Comparison_of_Criminal_and_Financial_Details_of_Re_elected_MPs_in_Lok_Sabha_2014_elections%20.pdf

In 1999, democracy watchdog ADR filed a public interest litigation or PILwith the Delhi High Court regarding the disclosure of the criminal, financial and educational background of the candidates taking part in elections. Although the PIL was upheld by the Delhi High Court in 2000, the Union Government challenged the verdict in Supreme Court.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

On 25 September, the Supreme Court of India delivered a major judgment directing the Election Commission (EC) to take immediate measures to address the rising criminality in the country’s politics. Highlighting the importance of full disclosure to public, a five-judge Constitution bench, headed by Chief Justice Dipak Mishra, observed that the voters should have all information about antecedents of their candidates so as to be able to make an informed and competent choice while exercising their voting rights. The court was responding to the petition filed by a well-known democracy watchdog, The Public Interest Foundation, requesting the highest court to debar candidates facing serious criminal charges from contesting elections.

The major highlight of this important judgment was its five directives to the Election Commission of India. These were: (1) A candidate must fill in the prescribed form. (2) The candidate must fill in bold letters that he is implicated in some crime. (3) The candidate must inform his party that he is implicated in some crime (4) On receiving information from a candidate of his criminal antecedents, the party must put this information on its website. (5) The criminal antecedents should be published by the candidate and his party in newspapers, which are widely circulated in the locality. In short, the 100-page judgment by the SC explicitly cited its concern over the sufferance of Indian democracy because of ‘unsettlingly increasing trend of criminalisation of politics’.

The key takeaway of the judgment was the court urging the legislative branch to frame a ‘strong’ law that would make it obligatory for political parties to remove leaders charged with “heinous and grievous” crimes, such as murder, rape and kidnapping and deny ticket to the offenders. The SC made it clear that it should not be expected to legislate for the Parliament. It observed that rapid criminalisation of the country’s democratic politics cannot be curbed by merely disqualifying tainted legislators. It needs much more, including the “cleansing” political parties. This important judgment has come for heavy flaks from the political analysts and democracy watchdogs for its “prescriptive tone” and “missing historic opportunity” to tackle one of the most serious challenges to democratic politics. Analysts feel that the SC bench that never misses an opportunity to exercise ‘judicial activism’ on all kinds of issues, including corruption, environmental pollution, civil liberties, among others, has taken a tactical safe route to avoid confrontation with the legislative branch. In short, the judgment has aroused a significant debate on the nature and extent of judicial power in India.

On 25 September, the Supreme Court of India delivered a major judgment directing the Election Commission (EC) to take immediate measures to address the rising criminality in the country’s politics. Highlighting the importance of full disclosure to public, a five-judge Constitution bench, headed by Chief Justice Dipak Mishra, observed that the voters should have all information about antecedents of their candidates so as to be able to make an informed and competent choice while exercising their voting rights. The court was responding to the petition filed by a well-known democracy watchdog, The Public Interest Foundation, requesting the highest court to debar candidates facing serious criminal charges from contesting elections.

The major highlight of this important judgment was its five directives to the Election Commission of India. These were: (1) A candidate must fill in the prescribed form. (2) The candidate must fill in bold letters that he is implicated in some crime. (3) The candidate must inform his party that he is implicated in some crime (4) On receiving information from a candidate of his criminal antecedents, the party must put this information on its website. (5) The criminal antecedents should be published by the candidate and his party in newspapers, which are widely circulated in the locality. In short, the 100-page judgment by the SC explicitly cited its concern over the sufferance of Indian democracy because of ‘unsettlingly increasing trend of criminalisation of politics’.

The key takeaway of the judgment was the court urging the legislative branch to frame a ‘strong’ law that would make it obligatory for political parties to remove leaders charged with “heinous and grievous” crimes, such as murder, rape and kidnapping and deny ticket to the offenders. The SC made it clear that it should not be expected to legislate for the Parliament. It observed that rapid criminalisation of the country’s democratic politics cannot be curbed by merely disqualifying tainted legislators. It needs much more, including the “cleansing” political parties. This important judgment has come for heavy flaks from the political analysts and democracy watchdogs for its “prescriptive tone” and “missing historic opportunity” to tackle one of the most serious challenges to democratic politics. Analysts feel that the SC bench that never misses an opportunity to exercise ‘judicial activism’ on all kinds of issues, including corruption, environmental pollution, civil liberties, among others, has taken a tactical safe route to avoid confrontation with the legislative branch. In short, the judgment has aroused a significant debate on the nature and extent of judicial power in India.

Source: Centre’s affidavit in Supreme Court (dated 11 September 2018)

Source: Centre’s affidavit in Supreme Court (dated 11 September 2018)

PREV

PREV