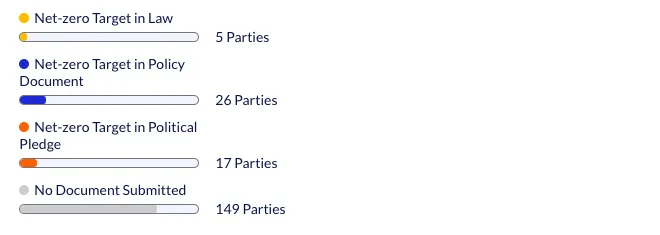

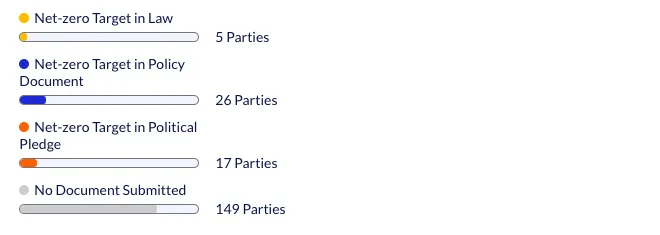

Many countries have made pledges for net-zero emissions, either through legislation or are in the process of formulating such policies. Five parties to the Paris Agreement have passed it as law so far (Figure 1). This is definitely a positive change but these plans and the impacts of these decisions are hard to analyse due to broad definitions of what constitutes “net zero”.

Figure 1 - Net Zero target by parties to the Paris Agreement

Data from climate watch data

Data from climate watch data

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defined it as bringing carbon dioxide emissions to “net zero” by 2050 to keep global warming to within 1.5 °Celsius of pre-industrial levels. However, there is no fixed definition of what constitutes net zero, leaving room for different interpretations. For example, the EU’s pledges target all greenhouse gases (GHGs), whereas China’s net-zero targets only carbon dioxide, leaving out methane or nitrous oxide. Overall, only 25 parties have included all GHGs in their pledges. Further, the data from climate watch shows that only five parties have included international shipping and aviation within the scope of their targets.

Companies’ net-zero goals also vary. Some such as Microsoft include net zero for carbon as well as to neutralise historical emission. Others pledge net zero for certain areas of their business while continuing to use fossil fuels in other areas. A study has shown that the commitments made across a sample of entities vary in quality on greenhouse gases covered, use of offsets, and whether the emissions cover company’s operations, value chains, and products.

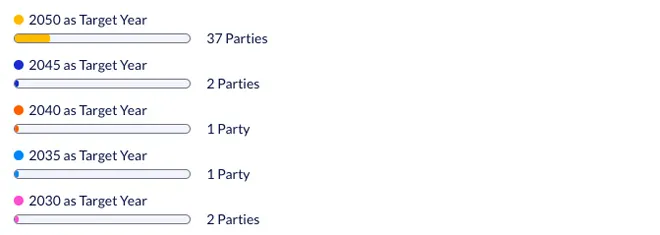

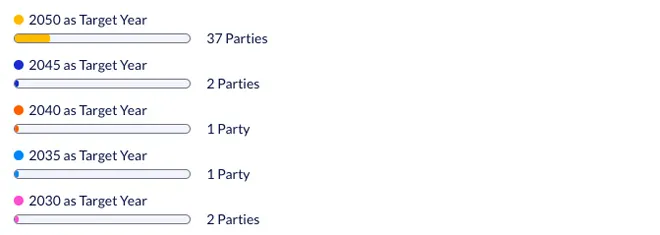

Then, there is the question of equity. 2050 is the common timeline agreed to by scientists to achieve carbon neutrality if the world is to keep temperature fluctuations within 2 degrees. The major contributors to cumulative emissions in the world today have set less ambitious targets that may not be sufficient to tackle the current climate crisis. Countries like the US need to have a more ambitious target for net zero by 2030; not what has been currently announced for 2050.

Figure 2 - Timeline for achieving net zero

Data from climate watch data

Data from climate watch data

Therefore, it would be a point of debate whether it is fair to put pressure on developing countries to adhere to the same timelines. Further, interim goals before we reach the 2050 target are important to affect economic decisions. Australia is yet to declare a timeline for carbon neutrality and is facing criticism for resisting calls for higher climate targets.

The US has recently committed to increasing its contribution to the US $100 billion climate fund. This is a positive step as it signals US re-commitment to the Paris Goals which had suffered a setback during the Trump era. However, it is not defined how the target will be reached. How much would each developed country contribute towards the fund or how much would go towards adaptation or carbon reduction investments. Moreover, now with climate change transition requiring investments in the range of trillions of dollars, this figure of 100 billion is only the baseline of what is required and is considered to be only the first step to meet the climate challenge.

Now with climate change transition requiring investments in the range of trillions of dollars, this figure of 100 billion is only the baseline of what is required and is considered to be only the first step to meet the climate challenge

Finally, there is the question of domestic versus international contributions to emissions. When countries report their national emissions to the United Nations, only fossil fuels burned domestically are counted. Australia has also faced increased pressure since the G7 meeting for its support for coal-fired fire stations. Australia is the largest exporter of coal. China also has invested in coal projects in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. Investing in dirty industries abroad would simply shift the burden of adaptation and mitigation to less developed and vulnerable countries in the future. Research has shown that offsetting is not a substitute for emission cuts. Data in figure 3 shows that there are only six parties that have excluded offsets from their targets.

Figure 3 - Data on international offsets

Data from climate watch data

Data from climate watch data

Removing greenhouse gases from the environment is a tricky affair. The technology for carbon capture is unproven and will require more investments. Other methods such as buying credits for green projects such as planting trees have risks involved too. The best approach forward would be to reduce direct emissions. But, it is clear that reducing reliance on coal is difficult. China, in its latest five-year plan, has stated that it will continue to use coal for energy security. For India as well, the focus now is on phasing down coal but phasing out will take longer. Given that nearly 70 percent of all GHG emissions come from fossil fuels, reducing and eliminating the share of coal is crucial.

Net-zero targets can play an important role if they are robust with interim targets and policies to help signal the private sector, businesses, and public sector so that investors and business decisions are shaped by it

Net-zero targets can play an important role if they are robust with interim targets and policies to help signal the private sector, businesses, and public sector so that investors and business decisions are shaped by it. India’s targets will be important towards achieving the climate goals and India would need to set stronger targets and have a roadmap for achieving net zero in the upcoming meeting. Methods and methodologies of how the progress of each country can be measured would be crucial to make comparisons easier and for accountability. Further, developed nations will have to take concrete steps to fulfil their financial commitments under the Paris agreement. Proportion of finance in the form of grants and concessional loans should be scaled up. COP 26 would be crucial and probably the last chance for countries to come together and discuss these important points and come to a consensus.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV