With the conventional presentation of the new defence budget at the National People’s Congress (NPC) on 22 May, the Communist Part of China (CCP) brought to a close not only a decade of Chinese defence strategy and budgeting, but also the endless speculation behind this new budget. The new defence budget for 2020 was declared at RMB 1.268 trillion ($178.6 billion), a 6.6% increase from RMB 1.19 trillion ($177.5 billion) in 2019. Although this increase has continued the trend of single digit increments since 2016, which ranged from 7.2% and 8.1%, it does indeed mark the lowest growth since 2010.

Yet, given the legacy of misinformation associated with the annual Chinese defence budget, this seemingly marginal increase this year can be deceptive. In order to counter such perceptions, China officially maintains that ever since 2007 it has annually submitted its defence expenditure to the UN. Nonetheless, this alleged information is available from the UN only for the years 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2017. More importantly think tanks like the Stockholm International Peace Research Institution (SIPRI) and the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) assert that even this basic information supplied is largely inaccurate with their own estimates of actual Chinese defence expenditure consistently falling significantly higher.

Given the legacy of misinformation associated with the annual Chinese defence budget, this seemingly marginal increase this year can be deceptive.

What appears from these claims and counter claims is that while ascertaining an accurate picture of Chinese annual defence expenditure is exceedingly difficult, there do indeed exist discernible trends in China’s defence spending which have remained uncompromised over the last decade. Over the last decade the Chinese fiscal-military machine has grown proportionately together with its economic growth, roughly corresponding to its increase in defence expenditure. This has resulted in its defence budget remaining consistently at 1.9% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) between 2010 and 2019, with the exceptions of 2011 and 2012 where it fell to 1.8% of its GDP.

Notwithstanding the gradual decrease in the share of defence budget in government expenditure form 7.64% in 2010 to 5.4% in 2019, the increasing rapidity of Chinese economic growth has made the total of the seemingly reduced expenditure year-on-year considerably large in absolute terms, expanding in SIPRI’s estimates from $143.9 billion in 2010 to $266.5 billion in 2019. This is in stark contrast to the present situation in which the Chinese economy in the post-COVID-19 world is predicted to face considerable economic turmoil with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projecting the growth of the Chinese GDP to fall from 6.1% in 2019 to merely 1.2% in 2020.

Apart from arguments supporting the need for a Keynesian stimulus through an increased expenditure on defence, this disparity has been sustained by the logic that the People’s Liberation Army needs sufficient funds since it has been instrumental in tackling the current COVID-19 pandemic.

This discrepancy between the projected Chinese GDP and its defence budget for 2020, clearly stands out from past practice where an increase in Chinese defence expenditure has been justified by an equally strong GDP. Presently, apart from arguments supporting the need for a Keynesian stimulus through an increased expenditure on defence, this disparity has been sustained by the logic that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) needs sufficient funds since it has been instrumental in tackling the current COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless of such justifications, what remains apparent is the continuity of certain trends in Chinese defence budgeting over the last decade.

Xi Jinping in 2012 inherited a rising China from Hu Jintao and restructured its goal from building a “harmonious society” which endeavoured to “hide capabilities and abide time” under the ‘Tau Guang Yang Hui’ principle, to actively attempting to “stepping out from Tau Guang Yang Hui”. Xi’s goal for China was clearly articulated in his speech at the 19th National Congress of the CCP held in 2017 where he elaborately described his two stage plan in which “socialist modernisation” is to be realised by 2035. Subsequent to this, China is to become a “global leader in terms of composite national strength and international influence” by the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China in 2049.

Xi’s goal for China was clearly articulated in his speech at the 19th National Congress of the CCP held in 2017 where he elaborately described his two stage plan in which “socialist modernisation” is to be realised by 2035.

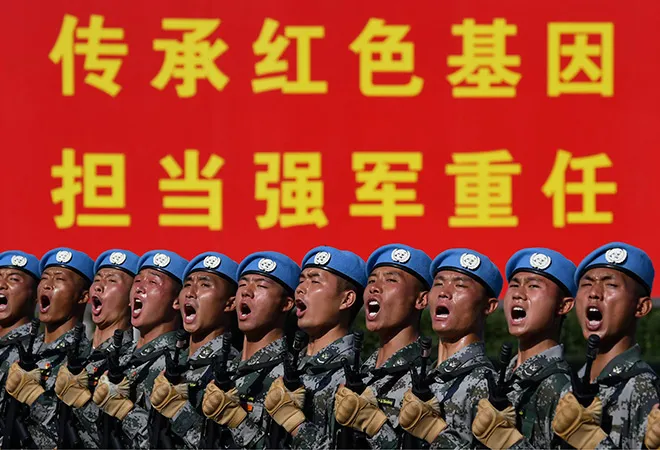

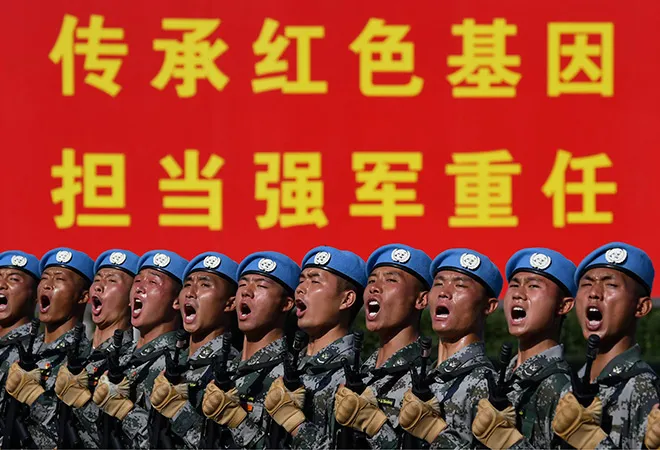

The politicisation and direct control of the PLA by the CCP has been an integral part of fulfilling Xi’s socialist modernisation right from the beginning. For the most part of the last decade an investment in military personnel was crucial for securing a favourable external and internal environment for the socialist modernisation. In fact, the White Paper published in 2019 states categorically that the increased military expenditure has been mainly spent on “military salaries, and bettering the working, training and living conditions of the troops,” amongst other aspects of the PLA Army (PLAA).

More pertinently, what the White paper refers to as the new ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ (RMA) through the ‘informationisation’ and ‘mechanisation’ of the PLA still remains largely unfinished. This attempted modernisation under the principle of ‘active defence’ has been an ongoing endeavor through an ‘above the neck’ and ‘below the neck’ approach which essentially means restructuring the PLA leadership and reorienting the PLA’s internal structure respectively.

An increased focus on the PLAN is undoubtedly intended to project great naval power in both its backyard and the regional maritime order.

Focusing on Xi’s second stage which alludes to China’s global leadership and harnessing its international influence by 2049, the White Paper also suggests that the PLAA has been greatly downsized and its resources have instead been diverted to the PLA Navy (PLAN) and the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF). This increased expenditure on the PLARF is clearly geared to improving and strengthening the precision and capabilities of Chinese firepower. Consequently, an increased focus on the PLAN is undoubtedly intended to project great naval power in both its backyard and the regional maritime order. Interestingly, between 2014 and 2018 China outpaced the combined naval hull production of the German, Indian, British and Spanish navies.

With most of the world facing an economic recession due to the present pandemic, China’s mere 1.2% projected GDP growth for 2020 will undoubtedly pose problems for its recently declared defence budget, possibly leaving other critical areas like social welfare, job creation and poverty alleviation insufficiently addressed. While the combination of China’s logistical geographies and its associated existential threats will likely not abate, Xi will indeed have to strike a delicate balance between expenditure for defence and development in the years to come. The old cliché which views development and defence in China as one and the same thing will perhaps break with a global economic meltdown projected this year.

However, China’s preoccupation with completing a successful RMA through the modernisation of the PLA will inevitably require plenty more of what Christopher Storrs describes as “men, money and material” in the years to come. Furthermore, with Xi abolishing the term limit of his presidency in 2018, China’s current goals and trends in its defence expenditure are likely to continue. While China may continue to prioritise and increase its expenditure on its defence, its grand ambitions and the possible neglect of holistic internal development in the years to come may potentially risk an imperial overreach.

The author is a research intern at ORF.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV