With countries around the world pledging to zero-emission goals, the global demand for rare earth minerals has amplified. Rare earths comprise of 17 minerals that are indispensable to the manufacturing of smartphones, electric vehicles, military weapons systems, and countless other advanced technologies. Africa holds the promise of large, high-grade deposits of rare earth metals. For three decades, China has managed to secure mining deals across the African continent with the availability of cheap labour and weak regulations. Currently, the global annual demand for rare earth elements (REEs) is largely met by China, which has devoted itself to increasing its presence in Africa guaranteeing ambitious energy and technological transitions. However, even with the abundant availability of rare earth deposits in southern and eastern African countries, the region has not yet reached its full potential.

Table 1: World mine production and reserves

| |

Mine production |

Reserves |

| |

2020 |

2021 |

|

| United States |

39,000 |

43,000 |

1,800,000 |

| Australia |

21,000 |

22,000 |

4,000,000 |

| Brazil |

600 |

500 |

21,000,000 |

| Burma |

31,000 |

26,000 |

NA |

| Burundi |

300 |

100 |

NA |

| Canada |

- |

- |

830,000 |

| China |

140,000 |

168,000 |

44,00,000 |

| Greenland |

- |

- |

1,500,000 |

| India |

2,900 |

2,900 |

6,900,000 |

| Madagascar |

2,800 |

3,200 |

NA |

| Russia |

2,700 |

2,700 |

21,000,000 |

| South Africa |

- |

- |

790,000 |

| Tanzania |

- |

- |

890,000 |

| Thailand |

3,600 |

8,000 |

NA |

| Vietnam |

700 |

400 |

22,000,000 |

| Other countries |

100 |

300 |

260,000 |

| World total (rounded) |

240,000 |

280,000 |

120,000,000 |

Source: US Geological survey

Africa’s rare earth potential

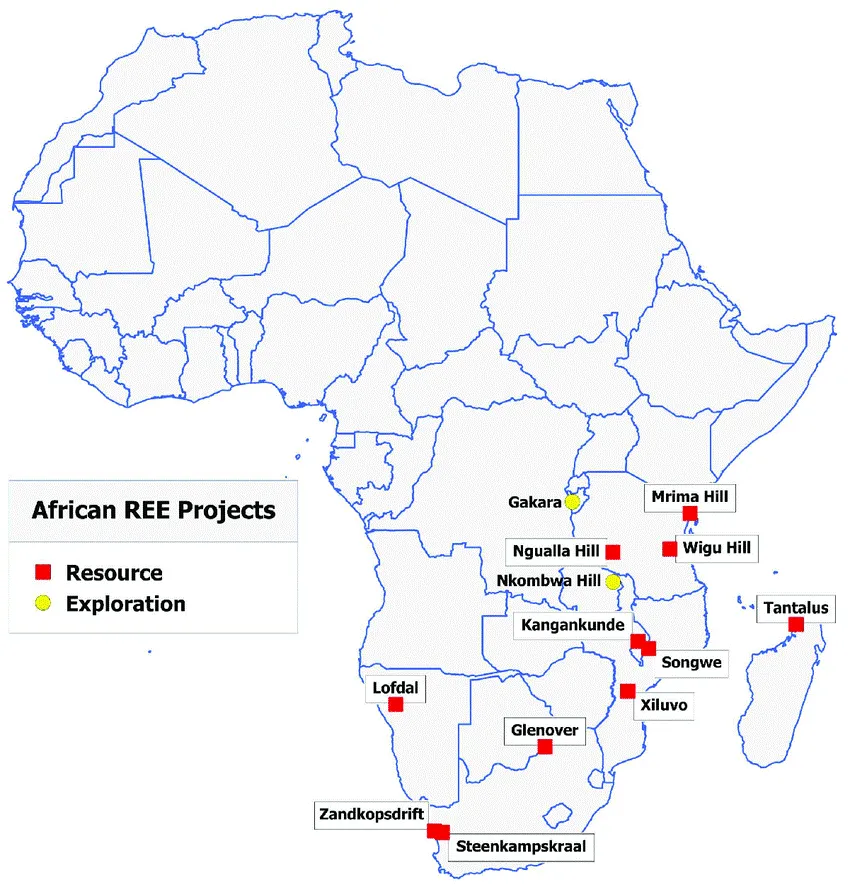

Africa has the largest mineral reserves in the world. Countries like South Africa, Madagascar, Malawi, Kenya, Namibia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Burundi have significant quantities of neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium.

Figure 1: Map showing REE projects in Africa

Source: Rare Earth Deposits of Africa

Source: Rare Earth Deposits of Africa

The Steenkampskraal mine in the Western Cape province of South Africa has the highest grade of these REEs in the world. With this, South Africa hopes to become a significant supplier in the world market. While relatively abundant, these elements are less minable than common ores. They can have direct technical applications or be used to facilitate the production and refinement of common high-technology products. Access to a steady supply of rare earth elements is key to the national security and economic viability of many countries across the world.

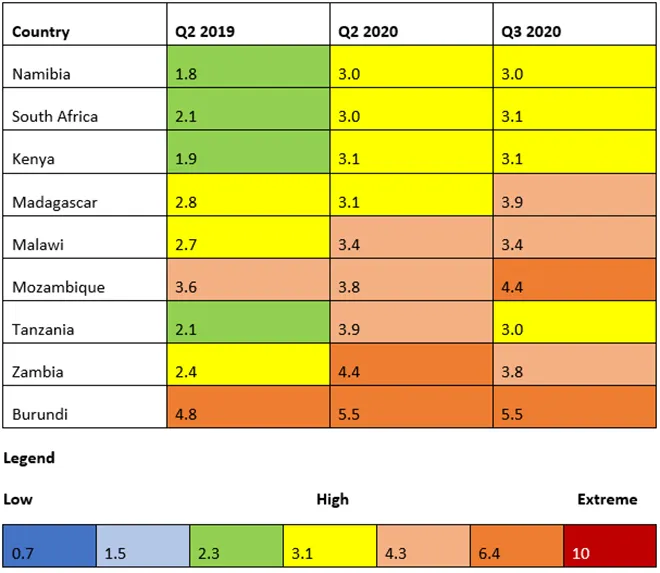

Table 2: Country Economic Risk Score

Source: his Markit

Source: his Markit

The above table shows the potential economic risks that Africa faces due to exploitation of REEs. In the third quarter of 2020, all the African countries faced high economic risk with Mozambique and Burundi facing the biggest threat.

Chinese footprint in Africa

Towards the end of 2010, the hunt for rare earths hit a high point as China, Japan, and South Korea showed keenness in acquiring these elements, with China raising trade-related disputes and controlling exports of rare earths and other metals. After the mining companies started realising the supply shortage, several new ventures were launched around the world, especially in Africa as the continent presented a perfect opportunity for these companies given the uncertainties in the field. The Chinese government took a major interest in the rare earth industry in the mid-1980s which allowed the country to gain a foothold in the global market. By 2011, China had developed cosy ties with resource-rich states, building infrastructure and providing loans in lieu of minerals from Africa.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) controls more than 70 percent of the world’s cobalt supply, mostly exported to China. For more than a decade, DRC was part of several mega infrastructure-for-minerals deals with Chinese mining companies, until recently, when it faced child labour and human rights complaints. Chinese-owned companies have been accused of opaque mining contracts exploiting Congo’s resources. In 2021, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s government reviewed the US$6 billion infrastructure-for-minerals deal with China due to concerns that the contracts were not adequately benefitting them. Despite China’s insistence that the deal was beneficial both ways, the Congolese government kept wary of Chinese companies and their control of the supply market.

Figure 2: Surging prices of REEs

Source: Bloomberg News

Source: Bloomberg News

Today, China is the dominant global supplier of rare earths. The Chinese control over the mine production works in two different ways. First, the Chinese companies downstream the processing of rare earth elements back in China, ensuring ownership control over the mining production. Second, as African markets are small with a limited fiscal base, they are forced to resort to international financing sources. Since the 2000s, China has been the single largest creditor in Africa and has played a key role in bilateral negotiations and strategies regarding finance. Given the transactional nature of foreign policy, China uses its economic leverage to achieve its long-term goals in the African continent.

Obstacles in the way

The global annual demand for rare earth is deemed vital for economic security. By 2025, the demand for REE is expected to be 304,678 metric tonnes from 208,250 metric tonnes in 2019. However, there are concerning issues with the production and distribution of REEs. All the rare earth deposits are mixed, so it is hard and expensive for processors to separate them and take advantage of their individual properties. It takes minimum a decade for REEs to materialise into significant profits. Furthermore, the lack of transparency in the global pricing of rare earth elements is a major obstacle. The Chinese domestic policies often govern the pricing of rare earth in the global market. During the rare earth trade disputes in 2011 and 2019, the prices of the elements shot up aggressively because China restricted exports to maintain supplies for domestic industries. In the global market environment, Chinese monopolistic firms limit pricing, impacting the Western production and supply chains. This method involves a monopolistic firm reducing its prices to a point wherein competitors do not make any profit or sometimes even not dare to enter the market. Even though these firms have lower potential in short-term profits, it enables China and its state-owned companies to maintain their position and long-term profitability.

All the rare earth deposits are mixed, so it is hard and expensive for processors to separate them and take advantage of their individual properties. It takes minimum a decade for REEs to materialise into significant profits.

Road ahead

The trade deficit and imbalance between China and Africa is in billions. Strengthening connectivity, infrastructure, and mining is the way forward for trade policy between the two countries. Even though China has been effective with various infrastructure projects in Africa, the lack of transparency in the deals, human rights violations, and unsustainable methods cannot be overlooked.

While China maintains its command, this position is now being challenged. The market dynamics change from time to time and without a diversified supply chain, China cannot control the global market. The United States is motivated, now more than ever, to minimise its vulnerability towards China and has actively discussed rare earth projects in the African continent. The European Union is also looking forward to reducing its dependency on China and establishing new strategic partnerships with the African countries. Moreover, Japan and Australia, the other major players in the rare earth market, are also trying to contain China and reduce its dominance in the African continent.

Keerthana Rajesh Nambiar is a Research Intern at ORF, Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV