This article is part of ORF's Research and Analyses on the unfolding situation in Afghanistan since August 15, 2021.

This article is part of ORF's Research and Analyses on the unfolding situation in Afghanistan since August 15, 2021.

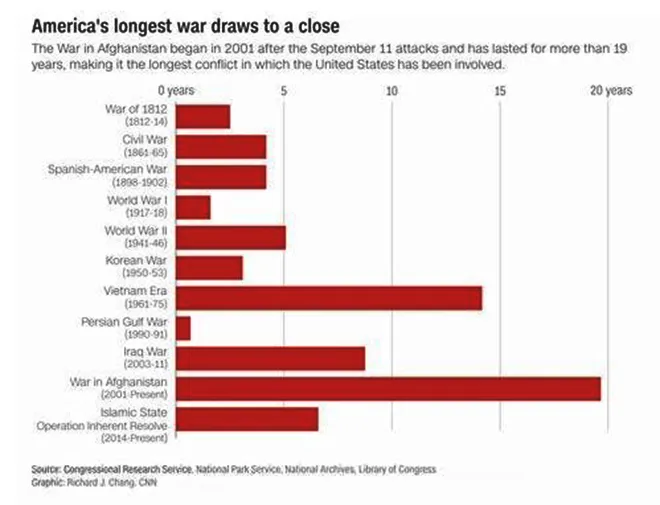

The United States and the Taliban signed a historic agreement on 29 February 2020, putting an end to the longest-running conflict in American history, which cost a hefty US $2 trillion and approximately 2,400 American lives. Consequently, President Biden announced the decision to withdraw all US troops from Afghanistan by 11 September 2021. On 16 May 2021, the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, called this withdrawal “hasty”, since this has severely affected the peace process and regional stability. Additionally, he called on the United Nations (UN) to play its due role and also urged the eight-member Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) to pay more attention to the situation. Yi also had a telephonic conversation with his Pakistani counterpart, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, on the 15th of May regarding the US withdrawal. Yi reiterated the all-weather ties that Pakistan and China have had in the past 70 years when it comes to each other’s core interests.

Source: CNN

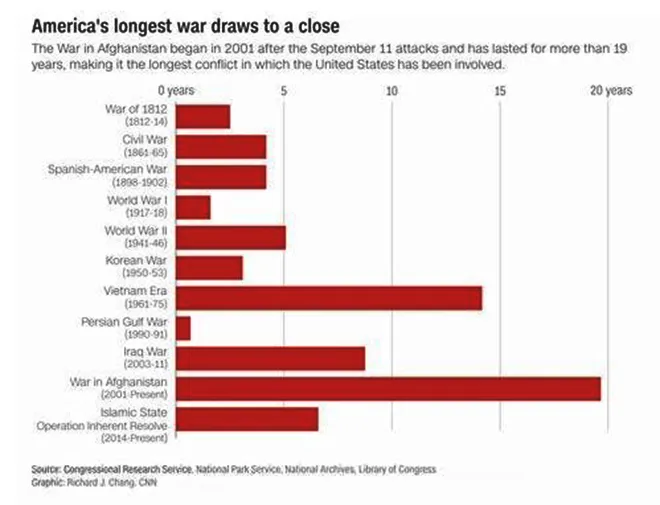

Source: CNN

So why is China so actively concerned about the withdrawal when China itself had termed American presence a “distortion of Afghan politics” and the cause for instability in China’s backyard? The abrupt departure of US troops despite the lack of prospects for a sustainable political settlement raises questions regarding stability, not just within Afghanistan but in the region as a whole. Regional neighbours like Pakistan and China could face far-reaching consequences in the form of grave security threats as well as economic challenges. Owing to their long-term alliance, China and Pakistan could be expected to continue their strategic coordination and exert a substantial influence on the prevalence of stability in Afghanistan. However, the withdrawal’s grave repercussions are likely to be felt by India too, in terms of security on the Northern frontier, and also vìs-a-vìs the enormous investments in Afghanistan. Thus, while the precedents would suggest that it is unlikely, post-US Afghanistan could give rise to the paltry possibility of cooperation between India, China, and Pakistan.

While the precedents would suggest that it is unlikely, post-US Afghanistan could give rise to the paltry possibility of cooperation between India, China, and Pakistan

Out of Afghanistan’s 398 districts, the Taliban controls 27 percent or 87 districts, and the government forces 30 percent or 97. The rest are contested, but the Taliban are stronger than they have ever been since 2001. Wielding unmatched influence in so many districts, the Taliban are unlikely to fulfill their end of the deal, because they believe that the Afghan government will be unable to hold them at bay. Taliban’s demeanour has also triggered cynicism regarding their commitment to the peace deal. A meeting scheduled in Istanbul on the 24th of April to fast-track negotiations between the government and the Taliban had to be indefinitely postponed after the Taliban delegation boycotted the meeting. As the last of the US troops withdraw from Afghanistan by September 11, recurrent display of this behaviour by the Taliban means that a political settlement will be impossible, and the Taliban will grab hold of a majority of power.

Source: Long War Journal

Source: Long War Journal

Ramifications for China

When the invasion happened in 2001, China saw it as the United States establishing a foothold in the heart of the Eurasian continent that could then possibly be utilised to contain China. Nevertheless, over the years, the Chinese have viewed the American wars since 9/11 as the best thing that could have happened to China, which gave Beijing a “window of strategic opportunity” for two decades to build their strength while Washington was distracted with these wars and bleeding trillions of dollars in these regions. This possibly provided China the leeway to inch closer to the US in the competition to become a global superpower.

China is usually known to oppose foreign intervention in principle, but unlike the Iraq War, Chinese leaders were notably supportive of the Afghan invasion, signing a United Nations Security Council Resolution censuring the Al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden, and calling for a new government. This was largely due to the acknowledgement that under the Taliban, Afghanistan was a source of tremendous instability on China’s borders, hosting militant groups and Uyghur extremist organisations demanding self-determination for Xinjiang, including one that was repeatedly blamed for terrorist attacks in China during the 1990s and 2000s. The withdrawal could potentially mean that Afghanistan could become an unhindered, safe haven for Uyghur militants, exacerbating China’s security concerns and diverting resources and attention from other areas of focus such as the South China Sea and the border conflict with India.

Ramifications for Pakistan

Pakistan shares a 2,670-kilometre boundary with Afghanistan and has been a safe haven for multiple militant outfits including the Afghan Taliban owing to its regional security interests vìs-a-vìs India. However, its strongest ally’s (China’s) interests in a stable Afghanistan, as well as the anticipation of additional security and other challenges following the US withdrawal, incentivises Pakistan to strive for peace in Afghanistan.

A US withdrawal, paired with China and India’s unwillingness to intervene in Afghanistan unilaterally, could mean that Pakistan might bear the entire burden of the impending chaos in Afghanistan. Rather than looking at Taliban as a singular entity, it must be recognised that there are various ethnicities and political forces within Afghanistan. Without an acceptable political settlement, the prospect of a civil war among these factions looms large. This could potentially precipitate a refugee crisis that could spill over to an economically floundering Pakistan. The Pakistani state, heavily dependent on loans, has recently been granted US $500 million by the IMF, in addition to the US $6 billion that had been sanctioned in 2019. Another major concern is that a Taliban takeover of Afghanistan could galvanise Islamist terrorists in Pakistan, including an already renascent Pakistan-Taliban, which could become a herculean security challenge for Islamabad. Additionally, Pakistan’s tribal belt, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), where militancy and demands for self-determination have been persistent, lie near the Afghan border. Any instability in Afghanistan could certainly spill over to these areas and aggravate the pre-existing security situation in Pakistan.

Ramifications for India

Failure to attain a political settlement would allow Pakistan to fall back on its most trusted proxies in the region, the Taliban. Pakistan might not hesitate to provide the Afghan Taliban with vital support against India, and this could directly challenge India’s security interests. India would also be wary of the Haqqani Network having a large role in any Taliban regime as well as the other India-focused militant outfits like the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohamed, which the Indian security establishment already believes to have relocated in large numbers to Afghanistan. An accentuated role for the Taliban in Afghan politics and the Islamism that it would foster across the region spilling over to Kashmir would be India’s biggest security threat. Coupled with the current COVID-19 pandemic that is still ravaging the country, domestic political challenges and the prolonged border disputes with China, India can ill-afford these security imbroglios in the North.

Unlike China, who has strategically engaged with the Taliban; and Pakistan, that has actively engaged with the Taliban; India has always been averse to the same. Post-withdrawal, Taliban is expected to dominate the political landscape, which could hinder India’s economic interests in the region. India has invested more than US $3 billion in developmental projects in Afghanistan since 2001. Resultantly, India might be compelled to re-orient its policies in Afghanistan, particularly its willingness to engage with the Taliban to safeguard interests. However, the recent joint EU–India press statement categorically states that India will not support a Taliban government in Afghanistan. Therefore, India’s staunch opposition to engagement with the Taliban despite high stakes could be extortionate on the economic front as well.

Unlike China, who has strategically engaged with the Taliban; and Pakistan, that has actively engaged with the Taliban; India has always been averse to the same. Post-withdrawal, Taliban is expected to dominate the political landscape, which could hinder India’s economic interests in the region

Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent statements urging the UN to play a due role has made it abundantly clear that the Chinese want stability in Afghanistan. China is Pakistan’s closest ally and has repeatedly provided assistance on economic (US $60 billon for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor), military and technical matters, as well dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. China supports Pakistan’s stance on Kashmir, while Pakistan supports China on Xinjiang, Tibet, and Taiwan. Therefore, in alignment with China’s wishes, Pakistan will quite certainly cooperate in Afghanistan. However, India’s cooperation with them remains in question because Sino-Indian relations have plunged into crisis since the 2020 Himalayan border conflict. Additionally, Indo-Pak relations have plumbed new depths too in the last few years because of Uri, Pulwama, Balakot, and the abrogation of Article 370, amongst other issues.

While India, China, and Pakistan are the fiercest regional neighbours, they are deeply bound by the imminent perils of formidable security and economic challenges of the post-US Afghanistan. Notwithstanding the various roadblocks that lie ahead regarding cooperation, it is in their best interests to help nurture peace and order in Afghanistan. China and India have been unwelcoming of this withdrawal, and contrastingly, Pakistan has supported the principle of responsible troop withdrawal. However, all three states have unequivocally welcomed the Afghan peace negotiations that underpin the desideratum of a negotiated political settlement and power-sharing. It is this shared desire for a stable Afghanistan which could sustain a possibility, albeit a faint one, of China–Pakistan–India trilateral cooperation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of ORF's

This article is part of ORF's

PREV

PREV