On 17 September, Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay port hosted a Japanese submarine Kuroshio for the first time in history. Though it was the first Japanese submarine visit, it was not the first Japanese vessel, and certainly not the first foreign vessel since the inauguration of the Cam Ranh International Port (CRIP) in 2016. The port has hosted several ships from various countries, including Singapore, Japan, India, China, the United States, France and Australia (see table 1). Thus, the CRIP is emerging as an important node in Vietnam’s broader foreign policy framework amid the wobbly waters of the South China Sea (SCS).

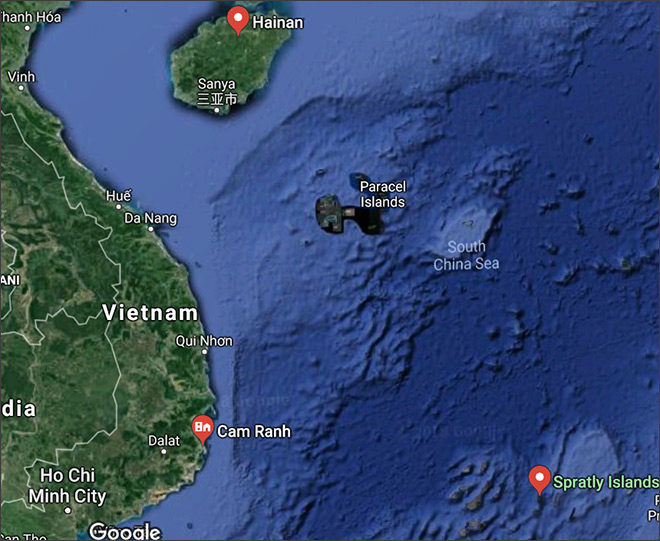

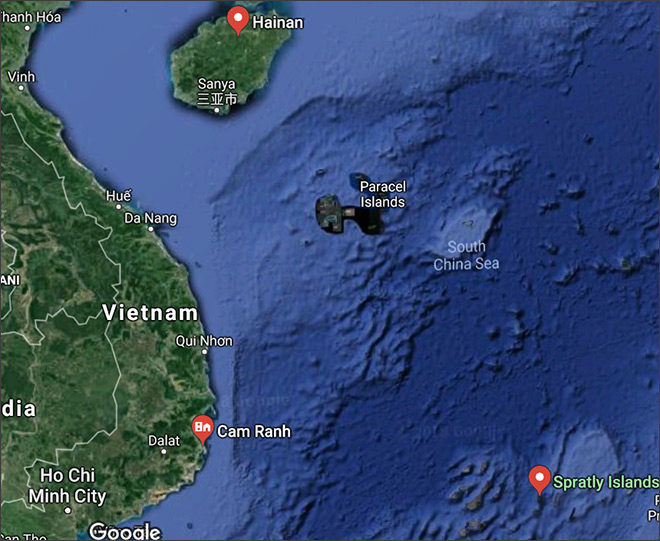

Map 1

Cam Ranh International Port vis-à-vis Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands and Hainan Island.

Cam Ranh International Port vis-à-vis Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands and Hainan Island.

Source: Google Maps

Cam Ranh Bay port straddles the vital Sea Lines of Communication in the SCS located at a distance of approximately 950 Nautical Miles (nm) from the Strait of Malacca, a strategic choke point. It is one of the best deep-water ports in the entire Indo-Pacific region conducive to dock submarines as well as huge aircraft carriers along with other naval vessels. The geographic location provides it with natural fortification against a possible attack. Additionally, it has excellent access to the resources required for an ideal port. It is no surprise, therefore, that the strategically significant Cam Ranh Bay port attracted colonisers and aggressors to Vietnam throughout history, beginning with the French. The Japanese exploited it during the Second World War, and the Americans used it during the Vietnam War. After the reunification of Vietnam, in the backdrop of the Sino-Vietnamese war in 1979, Vietnam leased the port to the erstwhile Soviet Union for twenty-five years. The lease ended in 2002.

Cam Ranh Bay port straddles the vital Sea Lines of Communication in the South China Sea located at a distance of approximately 950 nautical miles from the Strait of Malacca, a strategic choke point. It is one of the best deep-water ports in the entire Indo-Pacific region conducive to dock submarines as well as huge aircraft carriers along with other naval vessels.

In 2010, on account of aggressive Chinese behaviour in the SCS, Vietnam declared its plans to modernise and refurbish the Cam Ranh Bay port to commercially exploit its value by making it available to foreign vessels for repair, refuelling and docking. The first phase of the plan came to fruition in March 2016 after which foreign ships including aircraft carriers started calling on the CRIP, with the Japanese submarine being the latest one. By opening the CRIP for “all” foreign partners, Vietnam made sure that she conformed to her stated policy of diversification in foreign relations without a rigid distinction between friends and enemies. Moreover, the Cam Ranh Bay port added a lever in Vietnam’s diplomatic arsenal to effectively deal with China in more than one way.

First, the geographic location of Cam Ranh Bay port is such that it is situated at approximately 323 nm, 431 nm and 462 nm away from Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands and Hainan island, respectively (see map 1). Moreover, its proximity to the Malacca Strait and China makes it an ideal place for smothering China in an extreme event such as war. Thus, by opening the port in a limited manner, Vietnam has subtly signalled China that it may go further to handover the port to China’s adversary if a certain red line vis-à-vis Vietnam’s territorial sovereignty is breached.

Second, if one analyses the list of countries from which naval platforms have visited the Cam Ranh Bay port so far, it is clear that except China all other countries agree to the broader principle of freedom of navigation in the open seas according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. It means that all the guests to the Cam Ranh Bay port are on the opposite page of that of China vis-à-vis freedom of navigation. Thus, although officially Hanoi is adhering to her “three-Nos foreign policy (no alliances, no foreign military bases, and no policies that could be construed as being directed against any one state),” it is employing the soft balancing strategy against China through the Cam Ranh Bay port.

Third, the reopening of Cam Ranh Bay port indicates Hanoi’s inclination to be a partner of major regional powers and at the same time, be a loose part of the US-stitched networked partnership in the wider Indo-Pacific. In recent years, Hanoi has deepened its security and defence relationship with the US and its partners. While doing so, it has not forgotten other major powers such as France and Russia. Given the limited space to manoeuvre due to her asymmetric relationship with China, both in the economic and defence realm, the Cam Ranh Bay port has become the best flexible instrument to manage China’s rise.

In spite of Vietnam’s stated position that the Cam Ranh Bay port will not become a foreign naval base, India has a special place in Vietnam’s strategic calculus. Hanoi has granted an exclusive access to Indian Naval Ships to use Nha Trang Port which is a stone’s throw from the Cam Ranh Bay port. No other navy has an access to Nha Trang Port except the US Navy’s hospital ship USNS Mercy was allowed to dock there in the month of May. This shows meticulous diplomacy on Hanoi’s part to achieve the desired end without compromising the stated policy. It also exhibits the depth of the Indo-Vietnam strategic relations which was further broadened when two navies conducted joint naval exercises in May 2018.

In spite of Vietnam’s stated position that the Cam Ranh Bay port will not become a foreign naval base, India has a special place in Vietnam’s strategic calculus.

Apart from having robust bilateral relations, India’s simultaneous friendly relations with the US and Russia perfectly fits into Hanoi’s omnidirectional foreign policy mould. India trains Vietnamese sailors for her newly inducted Russian Kilo-class submarines and pilots for her Russian Sukhoi Su-30 fighter jets. Likewise, India has a strong security partnership with the US which is consociating Vietnam in her broad strategy for the Indo-Pacific. Thus, the broad strategic convergence between India and Vietnam along with India’s image as a benign power allowed Hanoi to endow special privileges on New Delhi vis-à-vis access to Nha Trang Port. Additionally, India’s presence in the region does not invoke as sharp reaction from Beijing as it would have been with that of the US or Russia.

Vietnam does not want to be seen as taking an overtly adverse position against China in her quest to maintain the territorial integrity. The Cam Ranh Bay port is helping her to nurture and strengthen multiple security relationships. It is also ensuring a continuous foreign naval presence in the region — an undesirable proposition for China in its quest to be the sole controller of the SCS. Theoretically, sheer naval presence is a form of naval diplomacy that achieves multiple goals such as expressing intent, reassuring partners and deterring the enemy. The Cam Ranh Bay port is facilitating the same for Vietnam.

Table 1: Naval vessels hosted by CRIP since its inauguration in 2016.

| Date |

Country |

Naval Vessels |

| March 2016 |

Singapore |

RSS Endurance (Endurance-class Landing Ship Tank) |

| April 2016 |

Japan |

Ariake and Setogiri (Guided-missile destroyers of the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force) |

| May 2016 |

France |

FS Tonnerre (Amphibious Assault Ship) |

| May 2016 |

India |

INS Satpura (Shivalik-class Stealth Multi-role Frigate) and INS Kirch (Kora-class Corvette) |

| October 2016 |

the US |

USS Frank Cable (the Submarine Tender) and USS John S. McCain (Guided-Missile Destroyer) |

| October 2016 |

China |

PLAN Xiangtan (Type 054A Frigate), PLAN Zhoushan (Type 054A Frigate) and PLAN Chaohu (Type 903A Replenishment Ship) |

| November 2016 |

Australia |

HMAS Warramunga (FFH 152) (Anzac-class Frigate) |

| December 2016 |

South Korea |

ROKS Cheon Ji (Fast Combat Support Ship) and ROKS Chungmugong Yi Sun-sin (DDH-975) (Chungmugong Yi Sun-sin-class Destroyer) |

| December 2016 |

Philippines |

BRP Ramon Alcaraz (Frigate) |

| December 2016 |

US |

USS Mustin (DDG 89) (Arleigh Burke-class Guided Missile Destroyer) |

| May 2017 |

US |

USNS Fall River (T-EPF-4) (Expeditionary Fast Transport Ship) |

| May 2017 |

Japan |

JS Izumo 183 (Helicopter Destroyer) and JS Sazanami 113 (Takanami-class Destroyer) |

| June 2017 |

US |

USS John S. McCain (Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer) |

| June 2017 |

US |

USS Coronado (an Independence-class Littoral Combat Ship) |

| August 2017 |

US |

USS San Diego (LPD 22) (Amphibious Transport Dock) |

| June 2018 |

Russia |

Admiral Tributs (Udaloy-class Destroyer) Admiral Vinogradov (Udaloy-class Destroyer) and Pechenga (Tanker) |

| September 2018 |

Japan |

Kuroshio (Submarine of Japan's Maritime Self-Defense Force) |

The table has been assembled from data available in the public domain.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Cam Ranh International Port vis-à-vis Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands and Hainan Island.

Cam Ranh International Port vis-à-vis Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands and Hainan Island.  PREV

PREV