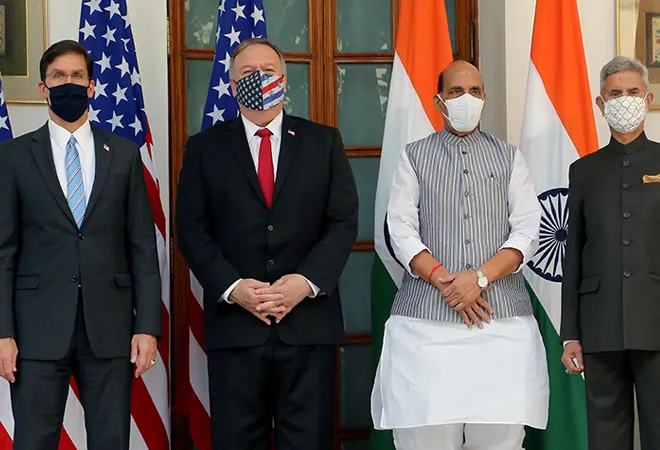

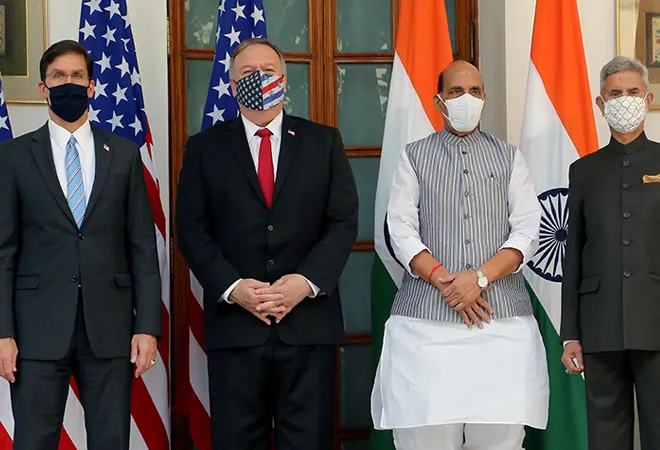

On Tuesday, October 27, India and the US signed the Basic Exchange Cooperation Agreement (BECA) on the occasion of the third ‘2+2’ in-person meet held between the Indian and US foreign and defence ministers in New Delhi. The agreement gives India access to classified US geospatial and GIS data.

India-US defence ties predate the strategic congruence that became evident after the Jaswant Singh-Strobe Talbott dialogue in the late 1990s, followed by President Clinton’s visit to India in 2000. In fact, they go back to efforts to develop defence technology ties during Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure between 1984-1989.

GSOMIA (a military information agreement) was the first of the foundational agreements to be signed in 2002 during the visit of Defence Minister George Fernandes to Washington DC. It essentially guaranteed that the two countries would protect any classified information or technology that they shared. It was aimed at promoting interoperability and laid the foundation for future US arms sales to the country.

There was a long stretch thereafter when the two countries continued to discuss various other foundational agreements, but nothing came through in the UPA years. It was only after the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 and the US had an unusually talented and sensitive Defence Secretary, Ashton Carter, that the two sides were able to work out the LEMOA (logistics exchange agreement) signed in August 2016 during Carter’s visit. It was the second agreement to be signed and required a great deal of negotiation since its implications went beyond the Indo-US plane. It provides the framework for sharing military logistics, for example for refuelling and replenishment of stores for ships or aircraft transiting through an Indian/US facility. The third agreement, COMCASA (communications security agreement) was signed during the inaugural ‘2+2’ meeting in September 2018. This is an India-specific version of the Communication and Information Security Memorandum of Agreement (CISMOA). COMCASA enables the US to supply India with its proprietary encrypted communications equipment and systems, allowing secure peacetime and wartime communications between high-level military leaders on both sides. Further, it also enables Indian aircraft and ships with the US-made equipment to communicate with each other and with the US seamlessly. Because of the lack of this agreement, India had operated the US-made C-17s, C-130s and P-8I’s with commercially available systems for nearly half a decade.

COMCASA enables the US to supply India with its proprietary encrypted communications equipment and systems, allowing secure peacetime and wartime communications between high-level military leaders on both sides. Further, it also enables Indian aircraft and ships with the US-made equipment to communicate with each other and with the US seamlessly

The BECA facilitates the provision of targeting and navigation information from US systems. As is well known, for example, that the GPS, which was developed by the Pentagon, has a classified section which is far more accurate than the one available for use by US in our cars. But in addition, missiles and systems require geomagnetic and gravity data if they want pinpoint accuracy. But, of course, having the data by itself doesn’t guarantee accuracy; your missile navigation systems must also be able to use this highly accurate data.

The BECA facilitates the provision of targeting and navigation information from US systems. As is well known, for example, that the GPS, which was developed by the Pentagon, has a classified section which is far more accurate than the one available for use by US in our cars

In themselves the agreements are fairly routine and should not be over-hyped. They are really about building trust and setting the trajectory for future relations. They are not the end, but the means to get there.

As of now, all of them would enable cooperation and exchange in a range of sensitive area, but they do not obligate the two countries to provide or service a particular requirement.

Also, it needs to be pointed out that in all the agreements except LEMOA, the traffic is really one way, i.e. from the US to India. To clarify further, our asymmetry ensures that the technology that needs to be protected and the service that is expected, will come from the US, whether it is military technology, encryption systems, or GIS data.

It needs to be pointed out that in all the agreements except LEMOA, the traffic is really one way, i.e. from the US to India. To clarify further, our asymmetry ensures that the technology that needs to be protected and the service that is expected, will come from the US, whether it is military technology, encryption systems, or GIS data.

However, India being a resident Indian Ocean power, is important from the LEMOA point of view. Indeed, India has to worry that by synchronising its systems with those of the US, it will enable Washington to enter its decision-making loop, something that no sovereign country would like, especially since we do not have an identity of views relating to Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran and have different perspectives on some important Indian Ocean issues. Even in the case of China, there are differences that would prevent whole-hearted cooperation.

These foundational agreements are a product of the American bureaucratic culture. They have scores of commitments around the world and their bureaucracy is particular in ensuring that they all fall into a legal framework.

This is what the Pakistanis realised too late. Islamabad thought that the bilateral defence agreement they had signed with the US in 1959 would compel Washington to aid them in war with India, but the pact was merely an Executive Agreement, not a treaty approved by the US Senate. Indeed, the US could have come to their aid in 1971 using that agreement with a much more friendly Administration in Washington, but it didn’t.

So, we need to be clear that the US is not obliged to provide us any technology that we want under GSOMIA, neither will it have any obligation to provide us geospatial data in every circumstance. Certainly, it is unlikely to assist India in any venture relating to Pakistan. In the case of China, this administration may be obliging, but that may not necessarily be true of succeeding administrations in the US. At the end of the day, the reality is that the US is the giver and India the receiver.

Likewise, of course, India may not necessarily provide logistics facilitation to US vessels, were they to be involved in a war against, say for the sake of discussion, Iran. But as this author’s Ph.D. supervisor once said, agreements are a scrap of paper, unless they are backed by a mutuality of interest at the given time.

What these agreements do is to provide a trajectory which may lead somewhere, in this case, a India-US military alliance. But we’re not there as yet. As the Pakistan case reveals, that even as formal allies, assistance does not automatically kick in.

However, it is undeniable that there is a lot of room for cooperation even short of a formal alliance. During the Raisina Dialogue in March 2016, the then chief of the US Pacific Command, Admiral Harry Harris had called on the two countries to be more ambitious, and perhaps undertake coordinated patrols in the South China Sea. But here we need to enter the caveat that Indo-US defence cooperation remains confined to the region under the responsibility of the US Indo-Pacific Command which ends in India’s western shores. But India’s primary naval challenge is in the western and north-western Indian Ocean. Just how these agreements can be finessed to serve our ends there remains to be seen.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV