Export involve thousands of workers, especially in the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) which contribute 40 per cent of the total export output. India is not a big exporter in the world and its share in the world trade is less than two percent. The Central government’s 2015 Merchandise Export from India Scheme (MEIS) aims at increasing that share to 3.5 per cent by 2020. The recent review of the export policy has yielded a bounty of incentives for exports towards meeting this ambitious goal because exports contracted in October 2017 by 1.1 per cent, instead of growing at a fast rate. The trade deficit (exports minus imports) has been rising and was $14 billion in October and perhaps the government is worried. November’s export performance is not likely to be much better. It shows the lingering adverse effects of GST on some sectors. The government has already doubled the incentives on readymade ‘garments and made ups’ to Rs 2743 crore.

India has been exporting many products (around 12,000) among which are sophisticated engineering and electronic items, chemicals, automobiles and pharmaceuticals but majority of India’s exports is in the labour intensive category. It is natural that with such a huge labour force (around 500 million) India will specialise in items that require more labour than capital. Besides, India has traditionally been famous for handmade goods in the world and the same trend continues even now.

The government has increased the incentives for all labour intensive sectors like agricultural products, marine products, leather goods, carpets. This may help the SMEs in job creation as the incentives would lead to higher production and faster export growth. But the problem with such sops is that the trickle down is always slow and often is not implemented at the grass root level and fails to benefit the labourers, artisans or farmers involved in export production.

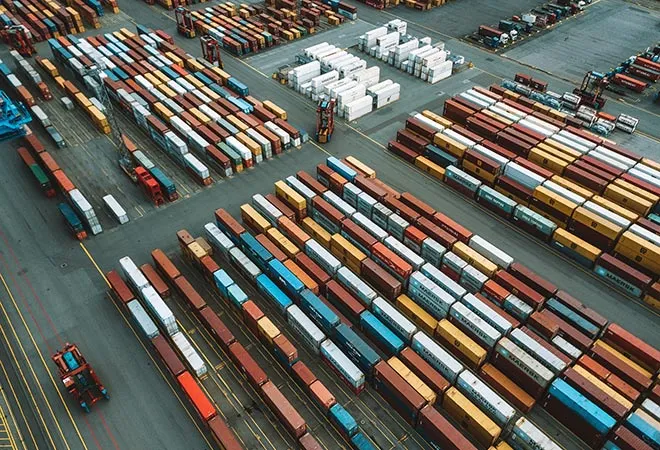

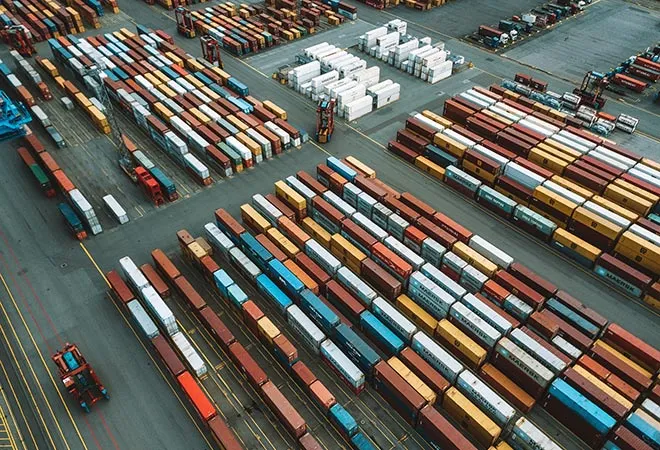

While the government is doing its best to boost exports especially when global trade is on the uptick, many hurdles remain for a vast country like India. The government’s freeing of imports for use in export production against self- certification is a good idea and increasing the time period for validity of duty credit scripts to 24 months will facilitate exporters to redeem such scripts over a longer time period. But there are many other problems which should be addressed. Indian exports especially in garments and ‘ready mades’ are competing against Bangladeshi and Vietnamese exports. There are other countries in Africa and Latin America making similar goods. Their labour costs are lower and the countries being much smaller, the transaction and transportation costs are also lower. They are favoured by the multinational corporations which are seeking high profits and are only looking for the cheapest supplier.

Simplification of procedures and single window clearance system will help and it is in the offing but competing countries have already streamlined such procedures before us. Improving the institutional framework in state governments will also help boost exports which involve reforming the export credit mechanisms in the states.

So much has been written on how India should be a part of the global value chain in which China and Bangladesh and others from ASEAN are present. The MEIS also refers to it and the Commerce Minister Suresh Prabhu spoke of it recently. The typical case which is often cited is the Apple I-phone, designed in the US but whose parts are made in diverse countries and assembled at a very low cost in China. The mark up in the final price is amazingly high by the company based in California. For India to enter the global value chain many things like port clearances have to be faster and easier. India is producing automotive parts already as part of the GVC but in many other engineering and high value electronic items, India could have participated. To be part of the GVC, high manufacturing growth and skilled labour are required.

Unfortunately, global manufacturing industry is experiencing a sea change and according to Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, the fall in wages and job losses are just collateral damage. Labour especially semi-skilled types are the innocent but unavoidable victims in the inexorable march of economic progress. According to Stiglitz productivity growth has outpaced growth in global demand due to the use of advanced manufacturing technology, robots and Artificial Intelligence. Even if manufacturing does increase in the future, the location of such units will not take place where jobs have been lost.

The idea of only highly skilled people being required in manufacturing in the future seems quite scary because in India only 10 percent of the labour force has any skills.

India, however, does have a potential in increasing agricultural exports and marine products but the markets in developed countries like the US have extremely strict standards for admitting agricultural imports. The Indian government is giving Rs 1354 crore for agriculture but even Britain is suffering in the case of its famed Blue cheese exports to the US this Christmas due to complex labelling norms requirement aimed at fobbing off foreign products. Similarly, the EU and Australia are extremely protectionist regarding agricultural products. Hence what will happen to India’s exports of agricultural products despite the sops is any body’s guess unless we diversify exports to developing countries like Afghanistan.

Instead of the total of Rs 8450 crore being spent on export sops, the government could have spent a little on refurbishing the social safety net for the informal sector workers engaged in export production. Their incomes could have been secured while they transitioned from one job to another or undertook skills training. India is bound to be affected by global trends in trade with its ups and downs in the fast moving technological world. If the welfare of workers is increased, their productivity and skills would rise and they would be able to participate in the global value chain which requires following standards and specifications to the minutest detail. It is a different world environment today than 10 years ago and even US President Donald Trump is worried about job losses in manufacturing. Job losses are inevitable when the whole business of manufacturing has become so capital intensive and India stands at a disadvantage because its main exports are labour intensive.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV