This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

Economic diplomacy is broadly defined as the aspect of diplomacy that focuses on international economic relations. In the post-Second World War context, this has usually meant promoting national trade, investment and technology interests through aggressive bilateral negotiations and pushing the same interests in multilateral institutions, such as the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Foreign assistance programmes were added as a bit of an afterthought to the principal objective of pursuing commercial goals.

India’s approach was different, and stemmed largely out of its own colonial experience and its desire to support other developing countries in their transition to independence. Within months of attaining its own independence, India drew upon its sterling reserves to give a major loan to Burma (Myanmar) in 1948. It also provided substantial development assistance to Nepal following the fall of the Rana dynasty in 1951<1>. India also joined the Colombo Plan in 1950 to offer scholarships for training in Indian institutions even while Indians were being sent overseas on other training programmes<2>. In 1960, India became one of the founding members of the Special Commonwealth African Assistance Programme. By 1966, it became the fifth largest contributor of scholarships to developing countries after the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand<3>.

India’s approach was different, and stemmed largely out of its own colonial experience and its desire to support other developing countries in their transition to independence.

A focus on skills development and capacity building remained the central tenet of India’s development cooperation efforts during those early years. It acquired a formal structure in September 1964 through the establishment of the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation Programme (ITEC) as “it was necessary to establish relations of mutual concern and inter-dependence based not only on commonly held ideals and aspirations, but also on solid economic foundations. Technical and economic cooperation was one of the essential functions of an integrated and imaginative foreign policy<4>.”

It was this ambitious statement of intent, carrying an unusual blend of altruism and pragmatism, that set the foundations of modern India's development cooperation architecture. Over the next five decades, India contributed to capacity building in countries across Africa and South and Southeast Asia. The emphasis was largely on the establishment of industrial estates and agriculture schools, in the deployment of technical experts for a range of projects, and in the training of a vast number of civil servants, technical personnel, doctors, nurses, engineers and scientists under ITEC<5>. In doing so, India made a clear departure from the monetarist principles followed by most Western donors, where the emphasis was on macroeconomic stability and budgetary support came with strict conditionalities. India took the structuralist approach, which argued that economic growth in developing countries is held back by persistent supply bottlenecks rather than macroeconomic instability<6>.

India made a clear departure from the monetarist principles followed by most Western donors, where the emphasis was on macroeconomic stability and budgetary support came with strict conditionalities.

A new dimension was added to India’s development cooperation framework around 2005 with the start of its first substantive lines of credit (LoCs) into Africa with a modest sum of US$ 500 million<7>. With soft interest rates that included a grant element ranging from 24.31 percent to 37.48 percent<8> backed by a sovereign guarantee, these LoCs contributed to the development of urban transport, irrigation and power transmission infrastructure in several African countries. India’s economic diplomacy also extended to its neighbourhood, with large LoCs being announced for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka in particular. By the end of 2019, India had committed as much as US$ 25.46 billion in LoCs to a range of countries<9> and also started to offer Buyer’s Credit to the tune of US$ 2.67 billion to encourage these countries to purchase Indian products<10>.

Over the years, India’s development cooperation model started to show some distinct features, namely:

• Respect for the recipient country’s sovereignty by staying clear of prescriptive reform agendas and conditionalities<11>

• Going with the recipient government’s priorities in terms of project selection

• Underscoring a mutuality of benefits, particularly in LoCs that require 75 percent of the funds to be spent on equipment and services sourced from India<12>

• Supporting capacity building through training programmes<13>. For instance, the various Information and Communication Technology (ICT) projects in the form of Centres for Excellence — across the African continent, Southeast Asia and Central Asia<14> — are built on a model that includes hand-holding for up to five years and then transferring control to a local entity.

At the same time, ambitious but often delayed connectivity projects in the neighbourhood — ning road, rail and river transport networks along with oil pipelines and power transmission grids — finally started to take shape under the direct supervision of the prime minister. India leveraged its satellite capabilities to offer education and health services through the e-VidyaBharti and e-ArogyaBharti programmes across the African continent and expanded the ITEC programme to provide 12,000 fully-funded training slots in courses ranging from cybersecurity and climate change to entrepreneurship and education<15>.

India’s participation in multilateral institutions sent a clear signal of its intent to participate in defining the new rules of the game and not remain a passive spectator to rules framed by others.

A more dynamic and responsive approach to development cooperation enabled India to engage in exceptional medical diplomacy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical teams were despatched to the Maldives, Nepal and Kuwait, and emergency consignments of medicines like paracetamol and hydroxychloroquine were sent to over 90 countries. This medical dimension of India’s economic diplomacy toolkit got a further boost as the manufacturing infrastructure of the Serum Institute of India allowed the country to launch its ‘Vaccine Maitri’ initiative to supply COVID-19 vaccines bilaterally on grant and commercial basis, and multilaterally through the Covax programme.

The dramatic expansion of India’s aid programmes under the Development Partnership Administration within the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) accompanied an equally vigorous push to the more conventional aspects of commercial and multilateral economic diplomacy. India’s diplomatic missions became actively engaged in organising trade shows and ‘Make in India’ events; pursuing market access and contesting non-tariff barriers; wooing multinational companies, private equity firms and sovereign funds to invest in India; and pursuing oil concessions and energy security arrangements. India’s participation in multilateral institutions sent a clear signal of its intent to participate in defining the new rules of the game and not remain a passive spectator to rules framed by others.

India’s positions on these and other new areas of economic diplomacy will be followed closely not just by competing countries but also by partners in the developing world who count on India’s advocacy to protect their own vital interests.

Nevertheless, India must now confront fresh challenges to its economic diplomacy. Globally, there are growing protectionist trends and a preference for bilateral over multilateral trade arrangements. A rising anti-immigration sentiment in major Western countries poses fresh hurdles to labour mobility. With artificial intelligence (AI), Fourth Industrial Revolution and 5G as the emerging factors of economic growth, India will have to retool its economic diplomacy. Setting up NEST as a new department in the MEA is a welcome initiative. If data is the new oil, India must develop clear and transparent domestic laws and institutions that create confidence in it being a safe destination for data processing. If climate change becomes an existential matter and pandemics like COVID-19 threaten to send the global economy into a tailspin, India must lead the conversations on matters like resilient infrastructure to global health. The impetus given by India to a global transition towards solar energy is a case in point — it not only took the lead in establishing the International Solar Alliance, but has also now provided LoCs worth US$ 2 billion<16> to fund solar energy projects in developing countries. India’s positions on these and other new areas of economic diplomacy will be followed closely not just by competing countries but also by partners in the developing world who count on India’s advocacy to protect their own vital interests.

In this new economic diplomacy, it is important to cast a wide net. Until now, much of India’s development cooperation has happened through state-to-state relations<17>, often carried out through state-owned enterprises. But there is exceptional work being done by leading civil society organisations (CSOs) in areas such as education, healthcare and financial inclusion. Several CSOs have developed models that can be scaled up and adapted in other developing countries. The growing demand from several countries for the Pratham<18> model of primary school education, for the Jaipur foot<19> to provide artificial limbs, for the Barefoot College<20> of women solar energy technicians, for SEWA’s success in promoting financial empowerment of women<21>, and for IndiaStack to configure Aadhaar-like solutions are cases in point<22>.

Analysing select startups, social enterprises and CSOs can help identify specific areas where the vigorous involvement of such organisations can play a vital role in advancing India’s economic diplomacy goals.

Tech startups

India has witnessed the emergence of a vibrant startup ecosystem that has piggybacked on the success and expertise of the IT industry. The ecosystem is the third biggest in the world<23> with the fourth highest number of unicorns<24>, which are foraying aggressively into global markets to solve challenges across multiple sectors.

The startup ecosystem is the third biggest in the world with the fourth highest number of unicorns.

Healthtech

Indian healthtech startups catering to diagnostic technologies, using compact devices and AI-powered software as a service (SaaS) products, can find great relevance in Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia. By improving efficiency and driving down costs of diagnoses, these startups can cater to the low-spending capacities of developing countries.

For instance, UE LifeSciences’ low-cost device for the early detection of breast cancer (iBreastExam) helps healthcare workers identify abnormalities in women at the point of care<25> and provides results within five minutes on a mobile application. The survival rate among women with breast cancer in Africa is far lower than in the US and Europe because detection happens at the advanced stages. Given the device’s portable and compact nature, hundreds of women can be scanned per day at remote locations<26>.

Table 1: List of Indian Healthtech Startups with Potential Relevance in Africa and Asia

| Organisation |

Location |

Core Function |

More information |

| Nirmai<27>) |

Bengaluru |

AI-based SaaS to detect breast cancer |

Developed a cancer screening solution that uses Thermalytix. It detects breast cancer at early stages . |

| Forus Health<28> |

Bengaluru |

Pre-screening ophthalmological medical devices |

Develops and manufactures portable and affordable medical devices for effective management of visual health through pre-screening ophthalmology. |

| Qure.Ai<29> |

Mumbai |

AI-based SaaS products to detect Tuberculosis and brain injuries |

Qure.ai uses AI algorithms for medical imaging. Through deep learning technologies, trained using million images, their products denitrify and localise abnormalities on X-Ray, CT and MRI scans. |

| BioScan Research<30> |

Ahmedabad |

A non-invasive, portable and fully automatic

point of care screening device for quick detection of intracranial haemorrhage. |

Selected as a part of the International Finance Corporation’s TechEmerge Health East Africa to pilot their tech solutions in the East African market. |

| Bempu Health<31> |

Bengaluru |

Wearable devices for maternal and child health |

| Coeco Labs<32> |

Bengaluru |

Coeco Labs has pioneered an

AI-based secretions and oral hygiene management device and a neonatal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure device |

|

Tricog<33>

|

Bengaluru |

Uses cloud and AI technology to provide virtual cardiology services to remote clinics. |

Edtech

India’s vibrant edtech ecosystem comprises of 4,450 startups and is home to the world’s highest-valued EdTech unicorn, Byju’s<34>. Using English as the primary mode of instruction, Indian edtech products can scale globally. While Indian edtech can cater to various levels of education, research has shown that edtech interventions for primary and secondary education in Africa are far more complex and will require significant complementary actions from civil society to be successful. Traditional Indian players like Byju’s cannot find immediate relevance at scale, but edtech products that cater to upskilling and tertiary education can. Along with its ITEC programme, India should also promote edtech startups (such as Simplilearn<35> and UpGrad<36>) that allow African students to remotely upskill at their own pace. Simplilearn provides online training in disciplines such as Cyber Security, Cloud Computing, Project Management, Digital Marketing, and Data Science. It has reached one million professionals and 1000 companies across 150 countries with certifications<37>. In Africa, it has partnered with South Africa-based Deviare to offer digital skilling programmes for students, professionals and enterprises and has received accreditation by South Africa’s Media, Information, and Communication Technologies Sector Education and Training Authority<38>.

Social entrepreneurs

Several Indian innovators have designed low-cost enterprise solutions across several sectors for societal wellbeing. While some of these solutions are exclusively for-profit ventures, others monetise the end-user for operational purposes.

Husk power systems

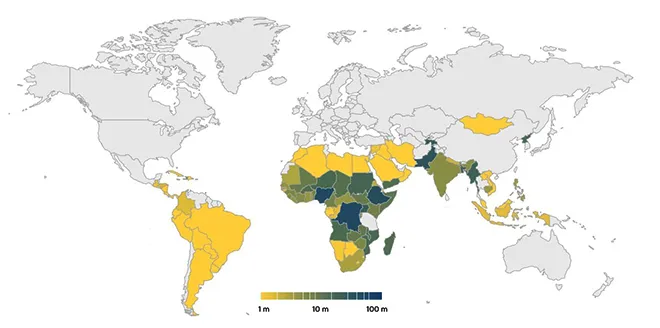

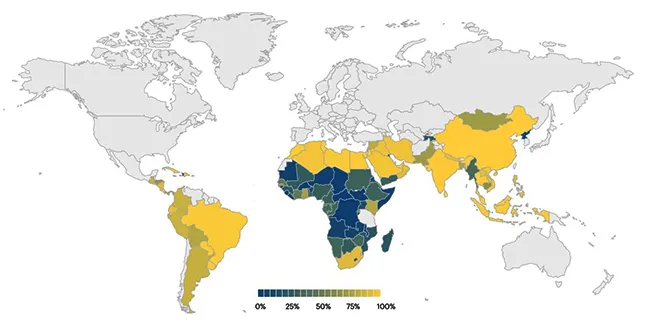

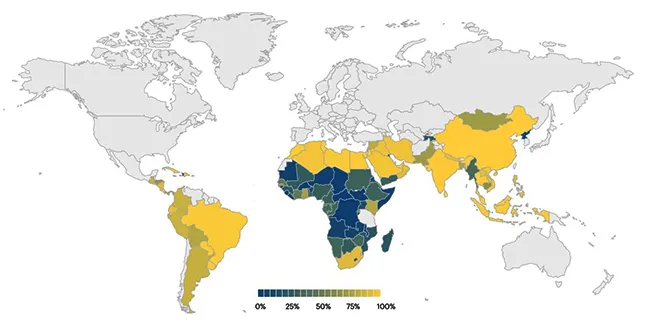

Husk power systems (HPS) provides off-grid power to rural Indian villages by converting biomass waste into clean energy. It costs less than US$ 1,200 per kW to install these systems, half the cost of solar panels of a similar scale<39>. The company also creates livelihoods by fostering first-generation power plant entrepreneurs and a technology workforce. Given Africa’s acute energy deficit (see Figures 1 and 2), HPS’s model can provide off-grid access to electricity while also creating livelihoods. HPS has already implemented projects in Tanzania and Uganda.

Figure 1: Population without Access to Electricity, 2019

Source: International Energy Agency<40>

Source: International Energy Agency<40>

Figure 2: Proportion of Rural Population with Access to Electricity, 2019

Source: International Energy Agency<41>

Source: International Energy Agency<41>

Waterlife India

Waterlife has pioneered a range of environmentally-friendly and cost-effective technologies that go beyond the standard reverse osmosis procedure and are fitted differently to cater to the size of the community, their drinking needs and the level of water contamination<42>. The company has installed 4,000 community water filtration systems across 12 Indian states, directly impacting 13 million people.

Aravind Eye Care

Aravind Eye Care is the largest and most-efficient eye care provider globally<43>. Its simple business and operation models allow for surgeries to be performed six times faster than the national average<44>, with over half of all patients (who come from poor and rural households) accessing high-quality care at no cost<45>.

Aravind’s assembly line surgery model — where labour is broken up for various tasks, and each ophthalmologist is supported by five or six paramedic staff to perform routine tasks while the former focuses on important procedures<46> — has improved productivity levels.

Aravind’s model has been replicated through collaborations in Ethiopia, Kenya, Zambia and Nigeria<47>.

Table 2: Social Entrepreneurs with Potential Relevance in Africa and Asia

| Organisations |

City |

Sector and Area of expertise |

Notes |

| Education Initiatives<48> |

Ahmedabad, Bangalore |

K-12 Education.

Undertake large scale student and teacher assessments to improve teacher capacities and learning outcomes. |

Pioneered Mindspark — a personalised adaptive learning (PAL) EdTech product — which is globally considered as the most promising EdTech product and has shown an improvement in students learning outcomes by 200-250%. |

| TIDE Learning<49> |

Bangalore |

K-12 Education |

Encourages self-paced learning by bringing unique teaching learning methodologies. |

| Krishna Arya Tech Corp |

|

Clean Energy |

Pioneered the ‘Annapoorna cookstove,' a zero-emission, low-cost, and energy efficient cooking solution that reduces biomass emissions. |

Civil society organisations

CSOs have been an integral part of India’s developmental journey, serving areas where the state and markets have failed to reach. While they solve problems contextualised to local settings, their learnings and lessons can be scaled in the developing world, or at least inspire and provide ideas for counterparts in these regions.

Swayam Shikshan Prayog

Swayam Shikshan Prayog (SSP) promotes inclusive sustainable development by empowering women in low-income and climate-threatened communities and regions. SSP’s model transforms women into entrepreneurs to tackle complex challenges across sectors such as health, water and sanitation, energy, food security and agriculture<50>. SSPs work has empowered 200,000 women and impacted six million households in 2,200 drought-hit villages across seven states in India<51>.

Given that several African countries are prone to drought, SSP’s work and learnings can find relevance in the continent.

Pratham Education Foundation

Pratham is known for pioneering two high-quality, low-cost and replicable interventions to plug gaps in education systems — the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER; a citizen-led survey that collects data on learning outcomes of 600,000 children across rural India) and Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) programme<52>. ASER is the only source of data on children’s learning outcomes in the country<53>, and has had a major impact on national policy and discourse. Organisations from 13 countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia are designing and implementing ASER surveys<54> through the People’s Action for Learning (PAL) Network –– a south-south network of organisations from three continents that are replicating and adapting Pratham’s ASER work in assessing learning outcomes.

TaRL builds foundational skills in numeracy and literacy in children with inadequate learning levels, a problem that is common in all developing countries. TaRL has been institutionalised in Africa as a joint initiative by Pratham and Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, and is operating in 10 countries in the continent through local partners<55>. The intervention is being funded by the US Agency for International Development<56>. It works directly with governments in Nigeria, Cote D’Ivoire and Zambia.

Operation ASHA

Operation ASHA (OA) aims to eradicate tuberculosis (TB) by solving the ‘last mile’ problem through community-based and technology-aided high-quality doorstep diagnosis and treatment services.

OA establishes community centres in urban slums in partnership with local community entrepreneurs, unemployed talent, merchants or religious institutions to serve 5,000-25,000 people within a 1.5-km radius. In rural areas, smart young adults from within the community are onboarded to ensure diagnosis and care of TB patients by transporting vital medicines to patients’ homes, monitoring compliance and assisting patients if travel to health facilities is necessary.

The cost of treatment per TB patient by OA is US$ 80 in India<57> as compared to US$ 1,900 per patient in Cambodia, US$ 3,575 in South Africa, US$ 14,059 in the European Union and US$ 17,000 in the US<58>. OA’s model has been replicated in many other countries such as Cambodia. Given the high prevalence of TB in Africa, OA’s work and global experience could be vital for the continent.

Conclusion

There is immense potential for tech startups, social entrepreneurs and CSOs to become partners in India’s development cooperation programmes. Proactively partnering with such organisations carries several distinct advantages:

• Leverages the passion, creativity, dynamism and domain knowledge of experts who have demonstrated the success of their models in India and may be keen on taking these to other countries

• Outcome-driven approach and grassroots understanding of key development challenges is likely to deliver better results

• Since such organisations have access to other sources of capital and do not rely on government funds alone, their engagement in development projects will be more cost-effective than the traditional reliance on state-owned enterprises who rely on full government funding for such projects.

• By promoting such organisations as the front end of its development cooperation efforts, India will be putting its best foot forward. There is a world of difference between the motivation levels, flexibility and working methods of these organisations when compared with the bureaucratic rigidities of state-owned enterprises. This, in turn, will promote Brand India and add to India’s soft power

• By introducing these organisations as agents of change in other developing countries, India has the opportunity to nurture global champions who have the bandwidth and scale to address emerging challenges

Several tech startups have the potential to change the development paradigm through their impact on the access and affordable delivery of education and healthcare. However, it is important to recognise the constraints inherent in relying excessively on technology-oriented initiatives in emerging economies in Africa and Asia that often suffer from lack of electricity or reliable internet. But Africa and Asia are also seeing rapid urbanisation and the growth of an aspirational middle class. Their cities have started to get reliable electricity and internet services, even as many rural areas remain laggards in this regard. Until the rural areas catch up, tech startups are likely to work best in urban situations while the grassroots approach of social entrepreneurs like Aravind Eye Centre or CSOs like Pratham will be more effective in plugging the gaps in less developed areas. A development cooperation agenda that recognises the strengths and limitations of each actor can tailor programmes that address the needs across a broad spectrum of the population.

Endnotes

<1> Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala, “Introduction,” in India's Approach to Development Cooperation, eds Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala (London: Routledge, 2016), xxxi-xxxv.

<2> Kumar Tuhin, “India's Development Cooperation through Capacity Building,” in India's Approach to Development Cooperation, eds Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 29-44.

<3> Tuhin, “India's Development Cooperation through Capacity Building,” pp. 30

<4> Embassy of India Brasilia, “ITEC: History,” Embassy of India Brasilia, Brazil.

<5> Tuhin, “India's Development Cooperation through Capacity Building,” pp. 31

<6> Saroj Kumar Mohanty, “Shaping India's Development Cooperation: India’s Mission Approach in a Theoretical Framework,” in India's Approach to Development Cooperation, eds Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 1-13.

<7> Persis Taraporevala and Rani D. Mullen, India-Africa Brief: Courting Africa through Economic Diplomacy, New Delhi, Center for Policy Research, 2013.

<8> EXIM Bank Official, e-mail to authors, 15 January 2021.

<9> Jayajit Dash., “Exim Bank's LoC Scheme to See Fresh Commitments Worth $20 Billion by 2025,” Business Standard, 6 March 2020.

<10> India EXIM Bank, “Government of India – Lines of Credit Statistics,” India EXIM Bank, 2021.

<11> Manmohan Agarwal, “Aid in India’s economic development cooperation,” in India's Approach to Development Cooperation, eds Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 14-28.

<12> Prabodh Saxena, “India’s credit lines,” in India's Approach to Development Cooperation, eds Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 60-78.

<13> Agarwal, “Aid in India’s economic development cooperation,”pp. 14

<14> Ministry of Electronics and Communication Technology, “International ICT Projects,” Government of India.

<15> Embassy of India in Senegal, “Opportunities for bilateral cooperation in Education sector,” Embassy of India, Dakar, Senegal.

<16> Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Government of India.

<17> Emma Mawdsley and Supiya Roychowdhury, “Civil society organisations and Indian developmental assistance: emerging roles for commentators, collaborators and critics,” in India's Approach to Development Cooperation, eds Sachin Chaturvedi and Anthea Mulakala (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 79-93.

<18> Pratham Education Foundation, “About us,” Pratham Education Foundation.

<19> Jaipur Foot, “The Organisation,” Jaipur Foot.

<20> Barefoot College International, “Barefoot International: a Global Mission,” Barefoot College International.

<21> Self Employed Women’s Association, “About Us,” SEWA.

<22> India Stack, “What is India Stack,” India Stack.

<23> “India emerges 3rd largest ecosystems for successful startups,” Times of India, 17 October 2019.

<24> Vasist Sharma, “Two-Thirds Of ‘Indian’ Unicorns Aren’t Based In India,” Bloomberg Quint, 5 August 2020.

<25> Kathleen Axelrod, “Meet Our New Innovators: UE LifeSciences,” Innovations in Healthcare.

<26> Axelrod, “Meet Our New Innovators”

<27> Niarmai, “Thermalytix,” Niarmai.

<28> Forus Health, “Our Purpose,” Forus Health.

<29> Qure AI, “About Qure.ai,” Qure AI.

<30> BioScan Research, “Products,” BioScan Research.

<31> Bempu Health, “Implementation,” Bempu Health.

<32> Coeco Labs, “Meet Coeco Labs,” Coeco Labs.

<33> Tricog, “About Tricog,” Tricog.

<34> International Finance Corporation, Cultivating a Love of Learning in K-12, BYJU’S: How a Learning App is Promoting Deep Conceptual Understanding that is Improving Educational Outcomes in India, Washington DC, World Bank Group, 2018.

<35> Simplilearn, “About Simplilearn,” Simplilearn.

<36> UpGrad, “UpGrad,” UpGrad.

<37> “Simplilearn Strengthens International Presence Partners With South Africa-Based Deviare Pty Ltd.,” The Week, 18 September 2019.

<38> “Simplilearn Strengthens International Presence Partners With South Africa-Based Deviare Pty Ltd.”

<39> Manoj Sinha, “Seeking an End to Energy Starvation (Innovations Case Narrative: Husk Power Systems),” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 6, no. 3 (2011).

<40> International Energy Agency, SDG7: Data and Projections on Access to Electricity and Clean Cooking, Paris, International Energy Agency, 2020.

<41> “SDG7: Data and Projections on Access to Electricity and Clean Cooking”

<42> Jubilant Bhartiya Foundation, A decade of recognizing entrepreneurs who make change happen, Jubliant Bharatiya Foundation and Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship, 2019.

<43> Aravind Krishnan, “Aravind Eye-Care System – McDonaldization of Eye-Care,” Technology and Operations Management, HBS Digital Initiative, 10 December 2015.

<44> Megan Leahy, Aravind Eye Care: Contributing to global capacity building of eye care personnel, Business Call to Action.

<45> Krishnan, “Aravind Eye-Care System”

<46> “Aravind Eye Care: Contributing to global capacity building of eye care personnel”

<47> Aravind News, “Aravind Eye Care System,” Aravind Eye Care System, 2014.

<48> Educational Initiatives, “Large Scale Education Programmes,” EI.

<49> TIDE Learning, “Welcome to TIDE Learning,” TIDE Learning.

<50> “A decade of recognizing entrepreneurs who make change happen”

<51> Swayam Shikshan Prayog, “Impact,” Swayam Shikshan Prayog.

<52> Anurag Reddy, “Embedding Technology in Education: The Potential of India’s Solutions in East Africa,” ORF Occasional Paper, Issue No. 306, March 2021.

<53> The Bridge Group, Changing the Public Discourse on School Learning: The Annual Status of Education Report, Mumbai, The Bridge Group, 2018.

<54> “Changing the Public Discourse on School Learning”

<55> Teaching at the Right Level, “TaRL in Action,” Teaching at the Right Level.

<56> “TaRL in Action”

<57> Wharton Stories, “Operation ASHA,” The Center for Health Market Innovations.

<58> “Operation ASHA: Scaling Up to Eradicate Tuberculosis in 25 Years,” The Wharton School.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication —

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication —  Source: International Energy Agency

Source: International Energy Agency Source: International Energy Agency

Source: International Energy Agency PREV

PREV