This brief is a part of The Ukraine Crisis: Cause and Course of the Conflict.

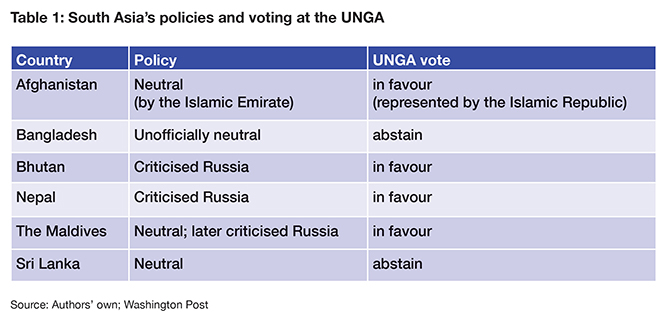

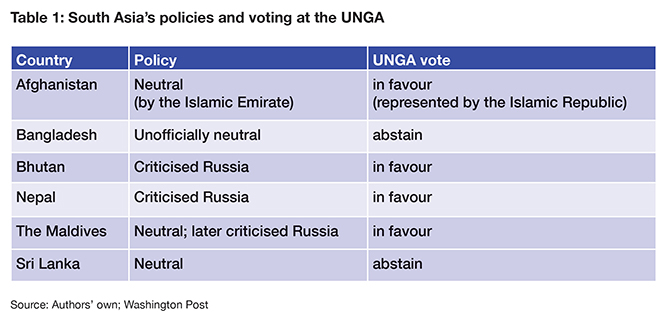

As Russia invades Ukraine, South Asia has responded distinctively to this crisis. Although a lot has been discussed about India and Pakistan’s realpolitik, less has been analysed about the responses from other South Asian states. These responses range from neutrality to calling out on Russia’s aggression, and are largely being shaped by the state's individual interests. The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting on the 2nd of March 2022, further explains this division (refer to Table 1). Nonetheless, these responses are tactical in nature and incapable to help these states navigate through the new systemic and strategic shifts emanating from Russia’s invasion.

| Country |

Policy |

UNGA vote |

| Afghanistan |

Neutral (by the Islamic Emirate) |

in favour (represented by the Islamic Republic) |

| Bangladesh |

Unofficially neutral |

Abstain |

| Bhutan |

Criticised Russia |

in favour |

| Nepal |

Criticised Russia |

in favour |

| The Maldives |

Neutral; later criticised Russia |

in favour |

| Sri Lanka |

Neutral |

Abstain |

Embracing neutrality:

Afghanistan and Sri Lanka have refused to take sides in this conflict and have embraced neutrality in their official statements. The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan has asked both parties to resolve the crisis through dialogue and peaceful means. Sri Lanka has urged the concerned parties to maintain peace, security, and stability through diplomacy and dialogue.

The Taliban’s statement of peace and neutrality is related to their broader project of seeking international legitimacy and aid. There is a belief that the crisis in Ukraine has the potential to deviate the world from Afghanistan and impact its aid and humanitarian funds. A preference for neutrality would thus be their best bet, as they are desperate for international aid and recognition, regardless of the source. It is also likely that the Taliban are insecure about the amplifying hostilities and rivalries considering the country’s vulnerabilities to geopolitics and great power rivalries. Finally, the Taliban might also be trying to promote a reformed image of themselves to the rest of the world. Their calls for peace and alleged efforts to evacuate Afghans who worked for the previous regime might be an attempt to exhibit the organisation as inclusive and peace-promoting.

The implications of the war, such as Ukraine’s economic devastations and sanctions on Russia will impact Sri Lanka dearly.

Similarly, the economic crisis in Sri Lanka has shaped its neutrality. Sri Lanka has been battling a severe forex crisis and debt problem, and evidently, the outflow and inflow of each dollar matters to the island state. It thus makes sense for them to not anger the West or the partakers of the conflict. In this case, Russia and Ukraine are also both important sources of its forex generation. They contribute over a quarter of Sri Lanka’s total tourist inflow. In addition, Russia is also one of the top importers of tea from Sri Lanka, and this alone generated a revenue of US $142 million in 2020 for the latter. The implications of the war, such as Ukraine’s economic devastations and sanctions on Russia will impact Sri Lanka dearly. Further, the increase in fuel prices, a potential delay in due payments and a slowdown of future purchases from the Russian importers have compelled Sri Lanka to request peace and stay neutral.

(Un)officially Neutral:

On the other hand, Bangladesh has embraced an unofficial policy of neutrality. It has urged both parties to return to dialogue and diplomacy. This stance is likely a compromise between its national interests and the discomfort of Russia’s violation of the UN Charter.

Russia is a significant development partner of Bangladesh. This partnership has been important for Bangladesh to graduate from its Least Developed Country (LDC) status and sustain its economic growth and energy security. Their trade was worth nearly US $2.4 billion in 2020 alone. It was also expected that Bangladesh would sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for a Free Trade Agreement with the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union this month. Further, Russia has also continued helping Bangladesh to sustain its energy security. Its state-owned Gazprom continues to have multiple contracts for drilling wells in Bangladeshi gas fields. Russia is also providing technical and over 90 percent of financial assistance to the latter’s first-ever nuclear power plant. The first and second units of the plants are believed to start production in 2022 and 2023. The former has also significantly invested in Bangladesh’s military hardware, garments, and fertiliser industries. It is perhaps this dependence on Russia that has shaped Bangladesh’s response.

Betting on the rules-based order:

Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives have taken a different stance. Nepal has been strongly critical of Russia’s actions since the invasion began. It has insisted on promoting dialogue and condemned Russia for violating the UN Charter and using force against Ukraine. Bhutan stated that it would study and assess the impacts of war and assured that no Bhutanese were stuck in Ukraine. However, it made its stance clear at the UNGA by reiterating its good neighbourly relations and stressed why upholding the values and principles of the UN Charter is vital for Bhutan and other small states. The Maldives has also not had an official statement on the crisis; its foreign minister had only asked both the parties to seek peace and political solutions. But, its recent vote at the UNGA indicated a change in its stance as well.

Nepal’s relations with Russia and Ukraine are limited. However, unlike Ukraine, Russia has provided helicopters, investments, and humanitarian aid to Nepal. Russia and Nepal’s trade summed up to be 10.2 million in 2019, and over 10,400 Russians visited Nepal as tourists in the same year. Nonetheless, these limited interactions still outweigh Nepal’s meagre relations with Ukraine. Similarly, Bhutan’s relationship with Ukraine and Russia are limited too.

Nepal continues to complain about border intrusions and encroachments from India and China, and Bhutan hasn’t yet demarcated its borders with an aggressive and salami-slicing China.

Their responses against Russia are thus seemingly a product of their geographical location and anxieties. Located between India and China, these states realise that they are at the heart of the power contestation. The Chinese invasion of Tibet and India’s annexation of Sikkim continues to apprehend these Himalayan states. Nepal continues to complain about border intrusions and encroachments from India and China, and Bhutan hasn’t yet demarcated its borders with an aggressive and salami-slicing China. In a true sense, their interests are in upholding and defending the UN Charter and the rights and independence of other small states as they presume to face similar challenges in the near future.

The Maldives’ relations with Russia and Ukraine are largely restricted to the tourism sector. Russia and Ukraine both provide the Maldives with more than 20 percent of the total tourists. In 2021 alone, the Maldives witnessed 208,000 tourists from Russia and 23,000 tourists from Ukraine. Similar to Sri Lanka, this war has also triggered concerns of post-COVID economic recovery for the island state. Therefore, compelling it to stay neutral and urge for peace. A change in the Maldives’ policy at the UNGA, however, indicates that the former is also carefully positioning its sovereignty and foreign policy as the competition in the Indo-Pacific intensifies.

Ready for the longer game?

Overall, these South Asian states have responded to this crisis by prioritising their national interests. These responses are, however, tactical in nature and incapable to help these states navigate through the systemic and strategic shifts emanating from Russia’s invasion. Strong sanctions on Moscow will likely complicate these states’ trade, tourism, economic growth, connectivity, energy security, forex generation, and military modernisation policies. Similarly, this crisis has also sparked and reinitiated the debates of the relevance of spheres of influence, reliance on geoeconomics for security, prospects of neutrality, alliances, and the West’s capabilities. For these states, accommodating these changes and challenges would be more of a challenge than taking a stance on Russia and its aggression.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV