The window of opportunity to combat climate change is closing fast. As such, the upcoming COP 26 summit that is taking place at the end of this month, is being reckoned as a ‘make or break’ in achieving global net zero by the middle of this century. Nations are expected to be ambitious in their climate action. While the developed nations are expected to be the frontrunners against climate change, developing nations are being expected to alter their development pathways to become compatible to the 1.5°C target. This puts immense pressure on developing nations such as India by compelling them to confront the trade-off between development and environment.

According to the United Nations’ Human Development Report (HDR) published in 2019, India is estimated to be home to 364 million poor people in 2019, approximately 28 percent of its population. The pandemic has further added to this number. The 2021 iteration of the Global Hunger Index ranks India 101 out of 116 nations with a score of 27.5 implying India’s hunger level as being serious. On the 2020 iteration of the Human Development Index (HDI), India ranked 131 amongst 189 nations with a score of 0.645 implying medium human development. India’s gross per capita income slipped to US$6,681 in 2019 from US $6,829 in 2018 in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP). These are a few indictors suggestive of the urgency of increasing development levels in the context of India. Such development demands a fair share of carbon space for its achievement.

Ban Ki-moon, former Secretary-General of the United Nations, referred to energy as the “golden thread connecting economic growth, social equity, and environmental sustainability.” It is this connection between economic growth and social equity that is explored in this article. Given that energy use drives production of goods and services, it has a significant positive bearing upon livelihood opportunities, and the infrastructural profile of a nation. Increasing energy consumption up to a certain threshold is associated with higher incomes and productivity as well as educational and health outcomes. Energy consumption involved in providing physical infrastructure such as communication and transportation are the lifelines of development as well as social infrastructure such as educational institutions, healthcare systems, sanitation, water supply, and housing,

A 2020 study by Srishti Gupta, et al. computed a Household Energy Poverty Index (HEPI) for India utilising a robust set of 15 key energy indicators representing multiple dimensions of energy. Households were categorised into four classes: ‘Least energy poor’, ‘less energy poor’, ‘more energy poor’, and ‘most energy poor’. The study found that 25 percent of the total households in the nation belonged to the ‘most energy poor’ category while 65 percent belonged to the ‘more and most energy poor’ groups indicating the extent of energy poverty in India. Clearly, there is a case for allocating a carbon budget to India for eliminating its energy poverty and achieving required levels of human development that has been precluded owing to this debilitating poverty. In this context, the critical question is how successful has India been in translating CO2 emissions into human development. The answer to this question bears upon the kind of strategies India needs to adopt to maximally leverage the carbon budget, if such a budget is granted to it.

The critical question is how successful has India been in translating CO2 emissions into human development. The answer to this question bears upon the kind of strategies India needs to adopt to maximally leverage the carbon budget, if such a budget is granted to it.

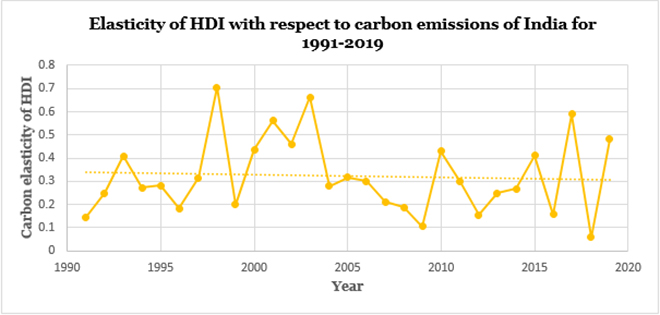

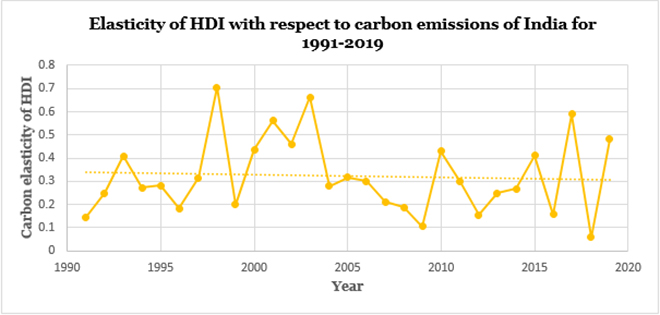

This question is answered by computing India’s carbon elasticity of human development for the period 1991-2019. The responsiveness (proportionate change) in the HDI scores to a change in CO2 emissions are computed for the 29-year period. The same measure is computed for the case of China which provides a point of reference in analysing India’s situation. China is the largest and India the third largest carbon emitter in the world with 10.17 and 2.62 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions respectively in 2019. Both these nations have been comparable in terms of both population levels and economic growth.

Figure 1: Elasticity of India’s HDI scores with respect to carbon emissions

Source: HDR-UNDP website, Our World in Data website and author’s own calculations

Source: HDR-UNDP website, Our World in Data website and author’s own calculations

The carbon elasticity of India’s HDI scores is clearly a time-invariant stationary process. The average carbon elasticity of India’s HDI is 0.32. This means that, on average, as CO2 emissions increase by one percent, the HDI score increases by 0.32 percent. This relative inelastic response of HDI implies a large cost in terms of CO2 emissions for a small increase in the human development quotient. Although more comprehensive than economic growth, the HDI captures progress made in certain dimensions of health, education, and decent standard of living. As such it is a limited representation of the broad term “human development.”

The years in which China experienced a decoupling of carbon emissions from development have been excluded from the calculation of elasticity of China’s HDI with respect to its carbon emissions. The average carbon elasticity of China’s HDI is 0.79 percent.

Despite being a developing country, the fact that China achieved decoupling must be acknowledged. This has been done by augmenting the average carbon elasticity of HDI to include the achievement of HDI in the decoupling years. A greater weightage is attached to this HDI achievement as compared to the average carbon elasticity of HDI in the normal years. The score arrived at reflects the actual achievement of human development in relation to its composite interaction with carbon emissions. For China, this score is 1.33. India does not have instances of decoupling. Therefore, India’s actual achievement of human development in relation to its composite interaction with carbon emissions is the same as its carbon elasticity of HDI i.e., 0.32.

These results are further corroborated by the carbon emissions embodied in the final demand for health and education in the two countries. Carbon emissions embodied in demand for education, on average for the 11-year period 2005-2015, accounted for 0.12 percent of that embodied in aggregate domestic final demand for India while the same stood at 0.21 percent for China. Carbon emissions embodied in demand for health accounted for 0.06 percent of that embodied in aggregate domestic final demand for India while the same stood at 0.15 percent for China. Here, the assumption is that greater percentage implies greater levels of educational or health activity, as the case may be.

Carbon emissions embodied in demand for health accounted for 0.06 percent of that embodied in aggregate domestic final demand for India while the same stood at 0.15 percent for China. Here, the assumption is that greater percentage implies greater levels of educational or health activity, as the case may be.

India’s low performance in human development in relation to carbon emissions may be explained by the following reasons: Firstly, the energy use and the resulting carbon emissions dedicated for activities driving human development is low. Secondly, even if there is a decent level of activity related to human development, the quality of the outcomes, for example in health and education, is low. Heavy reliance on coal has had a negative impact on human development: Coal-linked emissions resulting in death (about 11 deaths per hour) and disease (to 69 percent rise in diabetes cases, 76 percent increase in new asthma cases amongst children, and a 70 per cent increase in cases of stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease every year) as well as loss of productivity (loss of 85,86,300 workdays).

A way forward

Policymakers must draw their attention to these likely reasons. There is a need to allocate a greater energy and carbon budget to human development. There has to be a conscious effort to develop a roadmap to achieve this allocation. Causes of inefficiencies such as poor planning and governance, corruption, and red-tape, which explain poor quality of outcomes, cannot be afforded in the face of the existential threat posed by climate change. The limited carbon budget available cannot be wasted on account of these inefficiencies.

There is a focus on greening of production activity and of economic growth; green finance seeks to cater to such greening initiatives. Can the discussion also include green educational and health infrastructure, wherein renewable energy resources are used to power educational and health care institutions, and energy efficiency of electronic equipment used in education and medical care is promoted so that reducing the carbon footprint while simultaneously attaining development is prioritised? Green finance for building ‘green’ schools and ‘green’ hospitals can refer to a special form of green social impact finance which pursues people’s welfare and planet’s protection along with profits.

Finally, while these strategies are being put in place, the carbon budget needed by India to achieve an HDI score of around 0.8-0.9 needs to be determined and sought after at the global negotiating table. Furthermore, there is a need to conceive a development pathway that costs the least in terms of CO2 emissions and solutions in terms of finance and technology to make this development pathway 1.5°C compatible.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV