The US Congressional hearings on the “Anticompetitive Behaviour” of American tech giants namely Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google concluded last week with US Congressmen questioning their respective business practices. The hearings revealed the egregious practices adopted by these tech giants to dominate the digital market and to eliminate any potential competition using data. While what follows next is still unknown, a more detailed report on the findings of the year-long investigation is expected by August or September. The report will also substantiate the allegations with testimonies of past and present employees as well as internal communications and documents concerning business practices and key decisions taken.

Regulation of Big Tech companies is increasingly becoming inevitable as they wield enormous power over democracy, society and trade. The hearings held in the US are instructive for other countries and government officials who are looking to regulate the behaviour of big tech companies in their region. Countries such as India and South Korea are launching investigations. European Commissioner for Competiton Margrethe Vestager opened an investigation into Amazon earlier this year focusing on whether the company’s collection of data from merchants using its platform represented an unfair advantage. Now, the European Commission is thinking about tailoring its antitrust rules specifically to deal with such data sharing.

The hearings held in the US are instructive for other countries and government officials who are looking to regulate the behaviour of big tech companies in their region.

Here are some of points that regulators and governments need to consider as they attempt to understand these businesses and their anti-competitive behaviour.

The problem of many monopolies

Predominantly, there is a need for regulators to re-define and expand the scope of what is considered anti-competitive behaviour by companies. Competition law scholar Lina M. Khan directs attention to the fact that the current antitrust laws only measure competition through price and output but ignores the larger picture — the structural ways in which companies like Amazon are able to engage in anti-competitive behaviour. Khan explains that current discourse on antitrust law is dominated by the Chicago School of Antitrust Law whose principle states that the competition law should serve consumer interests above all else and the law should protect competition rather than individual competitors. A frequent defence that Big Tech companies assert when faced with antitrust investigations is — they are not a monopoly since they compete with their offline counterparts. To this end, Amazon cannot be a monopoly since it competes with the larger unorganised retail market and its participants. Google, in its defence into an Indian antitrust investigation in 2018, said that it does not have a monopoly in the online advertising space. Given the large advertising sector, it only accounts for a small percent as opposed to the offline players. It is becoming increasingly evident that despite the presence of competitors in the market, big tech companies are not ameliorating the competitive-ness of the market. Benedict Evans, an independent analyst and former partner at venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, captured this contradiction well in a tweet: “The great thing about tech monopolies is how many there are to choose from.”

A frequent defence that Big Tech companies assert when faced with antitrust investigations is — they are not a monopoly since they compete with their offline counterparts.

Big Tech companies own and operate marketplaces or act as intermediaries, and their behviour is increasingly looking more like monopsonies rather than monopolies. A monopsony results when a single company is the sole buyer of goods and services. For example, the governments act as a monopsony for defence sector for the purchase of weapons and defence equipment. Monopsonies distort the market with unfair contracts to suppliers and labour wages. Due to the dominant position that tech-mediated companies enjoy, they dictate the terms of the deal to third-party vendors and sellers. Thus, tech companies can set prices below cost for a product as compared to their offline retail counterparts. In Amazon’s case, third-party sellers are compelled to use Amazon’s in-house logistics services and participate in discount sales. Similarly, app-based taxi companies like Uber, Ola and Lyft can price their services lower by providing discounts to customers, while drivers on their platform are subject to unfair wage contracts with opaque algorithms dictating their behaviour and routes.

A marketplace and participant

As the hearings continued, Bezos was further questioned about Amazon’s practice of accessing and using third-party seller data to launch competing products. “We have a policy against using seller specific data to aid our private label business. But I can’t guarantee to you that that policy hasn’t been violated," Bezos said.

“You have access to data that far exceeds the sellers on your platforms with whom you compete. You can track consumer habits, interests, even what consumers clicked on, but then didn’t buy. You have access to the entirety of sellers’ pricing and inventory information past, present, and future. And you dictate the participation of third-party sellers on your platform. So, you can set the rules of the game for your competitors, but not actually follow those same rules for yourself,” Congresswoman Jayapal said to Bezos during the hearing.

These sentiments were echoed during the Competition Commision of India’s (CCI) investigation of e-commerce marketplaces like Amazon and Walmart-owned Flipkart. CCI’s investigation largely focused on the terms of engagement which forces sellers to discount their products. With this in mind, these marketplaces favoured their own in-house brands through private labels. The CCI questioned the ability of these platforms to maintain neutrality due to the inherent conflict in acting as an intermediary and a marketplace participant.

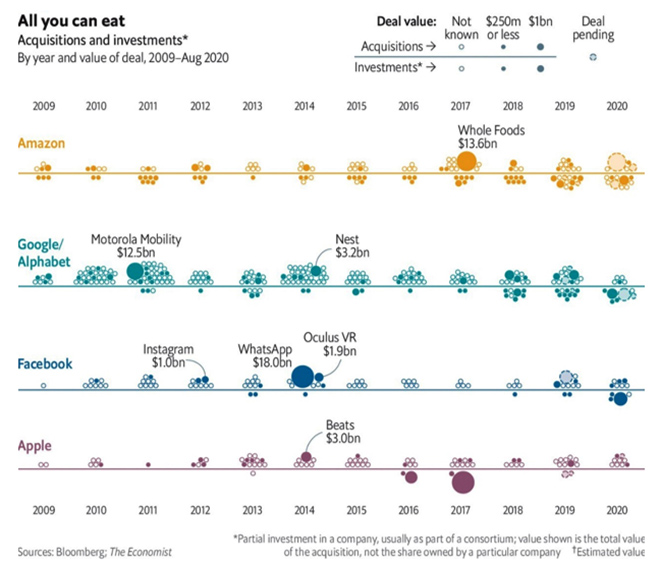

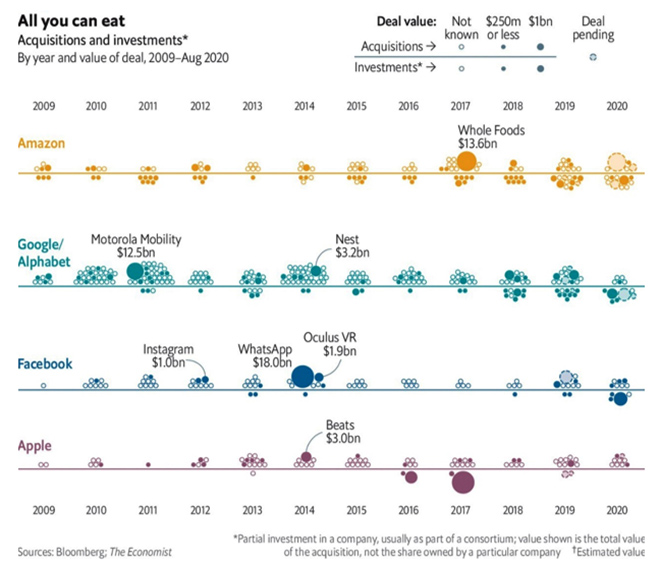

Source: The Economist

Source: The Economist

As the hearings proceeded, Apple was also grilled on launching competing products. Congressman Lucy McBath asked Apple CEO Tim Cook, why the company changed its rules which saw the removal of many parental control apps and then launching its own service ScreenTime. Cook defended the rule as the company had privacy concerns on the technologies that the apps used and exposure of children’s data to third parties and that these apps were restored and that there were more than 30 apps in the same space competing with Apple’s service. However, Congressman McBath questioned and countered on why the apps were restored after six months. “And of course, six months is truly an eternity for small businesses to be shut down, even worse if all the while a larger competitor is actually taking away customers,” she added.

An offline analogy can be found in in supermarkets where stores can launch their own brand for a particular product and may prioritise shelf space for their brand. The online version of this can be to alter search results to prompt users to buy their in-house brand.

For regulators, ensuring neutrality of platforms/marketplaces and balancing privacy concerns will be a challenge. As technology platforms play an increasing role in our lives, regulators will have to act more responsibly to ensure platforms do not violate privacy of their users and ensure safety. But at the same time, by the very nature of being platforms can collect incredible amount of data of their participants and the behaviour of their users. Nothing prevents these platforms from creating their own competing products and they may be very well in their right to do launch them. An offline analogy can be found in in supermarkets where stores can launch their own brand for a particular product and may prioritise shelf space for their brand. The online version of this can be to alter search results to prompt users to buy their in-house brand. To ensure impartiality, regulators can ask e-commerce companies to divulge information on their search algorithms. However, this may open another can of worms as this move would infringe on companies’ intellectual property.

Imitation isn’t flattering anymore

For over a decade, Big Tech companies were known as “drivers of innovation” or to fairly put across — they are working relentlessly to minimise the chances of another Amazon or Facebook. Through their track record, a similar pattern can be observed wherein tech giants are seen cloning features/innovations introduced by other smaller businesses, often startups. For instance, in 2011 Amazon reached out to Vocalife LLC’s inventor to explore the possibility of investing in a speech detection technology. Vocalife LLC met with Amazon’s employees and discussed its microphone technology and provided proprietary information, including engineering data. Shortly after the meeting, Amazon’s employees stopped responding to their e-mails. In November 2014, Amazon Echo was launched. While for start-ups, an opportunity like this is a breakthrough moment there lacks little knowledge on the power and dominance these big tech companies have on the market. There needs to be more scrutiny on the features that companies are introducing to allow small businesses to innovate and thrive.

Similarly, in the case of Facebook, around the same time when Facebook was working to develop a Facebook camera-app, Instagram was launched. Bearing in mind the threat of Instagram as a potential competitor, in 2012, Facebook acquired Instagram. At this step, Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal accused Facebook of “being a monopoly power that harvests and monetises data, and then uses that data to spy on competitors and to copy, acquire, and kill rivals.”

Our increased reliance has led to the gradual forming of each cog in the large machine that these companies are today.

What we are witnessing is the Big 4 Tech Giants successfully creating platforms that have impacted not only small businesses but also consumers, wherein a single decision can have affected the hundreds of millions of us in profound and lasting ways. Our increased reliance has led to the gradual forming of each cog in the large machine that these companies are today. Now, through access to information about marketplaces, use of disruptive digital infrastructure to surveil other companies to prevent rivalry and by exacerbating the fear of exclusion among small businesses — they have replaced these small cogs (here, small businesses) with their own single giant machine.

Regulation of Big Tech companies is increasingly becoming inevitable as they wield enormous power over democracy, society and trade. The pandemic has illustrated the dramatic dependency consumers and governments have on these tech giants, and this has placed their “anti-competitive behaviour” under the scanner. It is critical for administrators to review extant regulatory frameworks in order to ensure a level playing field in the digital market. The historic anti-trust hearing is a step in this direction, but its denouement has also raised questions as to what will follow next. Will we witness a reduction in the dominance of the tech giants, or will they continue to distort the market and stamp out competition? With the US presidential elections slated in November amidst the pandemic, will anti-trust be a priority for the elected president?

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV