This is the fifty eighth part in the series

This is the fifty eighth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles here.

Despite Indonesia’s huge archipelagic disposition, the maritime domain has for long been neglected in the policy calculus of the country. In the recent past, a change is underway, whereby Indonesia seems to finally realise and rediscover its “long-neglected maritime destiny.” This was evident in 2014, with the public announcement by President Joko Widodo of his vision to turn Indonesia into a Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF), given its strategic position, straddling the Indian and the Pacific oceans. The vision seeks to go beyond economic development internal to Indonesia and the mere enhancing of connectivity between the islands of the Indonesian archipelago. Broadly, it is focused on strengthening Indonesia’s maritime security; and expanding the canvas of regional diplomacy to cover the entire region of the Indo-Pacific. This change can mainly be attributed to Jakarta’s recognition of the emerging “great power contestation” in the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific.

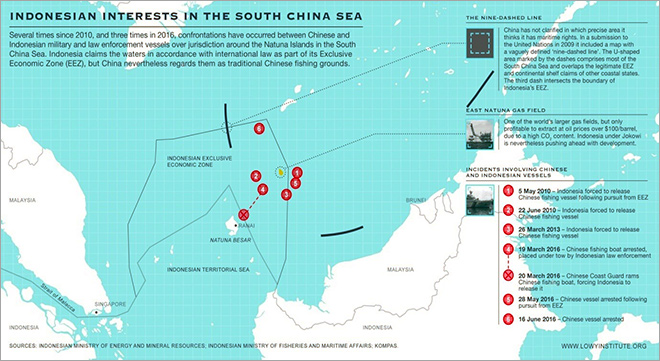

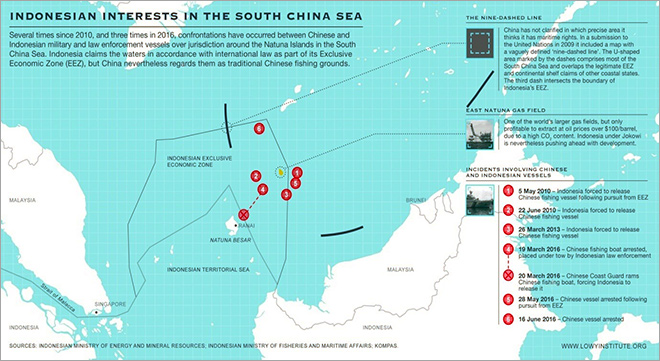

The fact that Indonesia is finally ‘thinking maritime’, can be seen from other moves being made by the country besides the ambition of turning Indonesia into a GMF state as well. Indonesia in July 2017, had renamed the waters northeast of the Natuna Islands, at the far southern end of the South China Sea (SCS), the 'North Natuna Sea'. Indonesian officials had also made it clear that only the part, which falls under Indonesia,’s claimed Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) was being renamed. This EEZ however, overlaps with China’s infamous nine-dash line. Though the Indonesians are not the first in the Southeast Asian region to rename their claimed zone in the SCS, what is important is that it is being done by a country, which has for long maintained that “

it is not part of the dispute over the South China Sea.”

The fact that Indonesia is finally ‘thinking maritime’, can be seen from other moves being made by the country besides the ambition of turning Indonesia into a GMF state as well.

Source: Lowy Institute

Source: Lowy Institute

There have been a number of incidents in recent years in Indonesia claimed EEZ in the SCS. The Indonesian navy has arrested Chinese fishing trawlers in the overlapping claimant zone. Though Indonesia still holds that “

it’s a non-claimant state in the South China Sea dispute,” Indonesia under President Jokowi has taken actions to beef up its military and law enforcement capacity in the area. The President himself has made two high profile trips to the military base at Ranai on Natuna Besar to demonstrate his interest in defending and protecting Indonesia’s sovereignty over the islands and Indonesian rights to the resources in the adjacent EEZ. These actions of Indonesia have been not irked China a great deal, and the renaming too carried no legal force. The actions underscored Indonesia’s narrow territorial and economic interests around Natunas and not on the SCS issue as a whole. These moves were not very provocative as it was in the case of the Philippines but just enough to ensure that Indonesia’s interests were secure. With this Indonesia has also managed to signal to other powers like India, Japan and the US that Jakarta finally is ready to take a stand on the SCS issue outside the platform of the ASEAN. It does demonstrate how Indonesia diplomatically and politically learning to “softly balance” against a rising China.

These actions of Indonesia don't irk China a great deal, and the renaming too carried no legal force. The actions underscored Indonesia’s narrow territorial and economic interests around Natunas and not on the SCS issue as a whole.

Indonesia has also been raising the SCS issue in international fora as well. For instance, during the visit of President Jokowi to India in December 2016, the Joint statement underlined the importance of the South China Sea, stressing “the importance of resolving disputes by peaceful means, in accordance with universally recognised principles of international law including the UNCLOS.” Even during the recent visit of the Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs, Luhut Pandjaitan to India in May 2018, he asserted “there should not be any power projection in the South China Sea and that Indonesia has very carefully responded to the issue.” Even while talking about Indonesia granting India access to develop the port of Sabang, located in the Northern tip of Sumatra and near the Strait of Malacca, he said in his personal view, “

this will ensure a bit of a balance in the South China Sea. A balance of power can be maintained.”

Indonesia is also one of the few countries in the Southeast Asian region, which has embraced the Indo-Pacific concept. Indonesia is taking note of the strategic rivalries, and the growing strategic and economic importance of the Indo-Pacific region. In February 2018, a Chinese naval task force comprising of four ships had entered the Indian Ocean from the Sunda Strait for exercising in international waters close to Australia and had exited via the Lombok Strait. Earlier in 2014, China held a three-ship naval exercise in the Indian Ocean, conducting a series of exercises including combat simulations. The task force had sailed through to the Western Pacific through the Lombok Strait near Indonesia’s Bali Island. Indonesia may not have issued official statements expressing its discomfort with these Chinese naval forces crossing its waters, but given Indonesia’s sensitivity to maritime sovereignty, these exercises can also be one of the reasons for it to be willing to seek a balance of power in the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific.

Indonesia is playing the balancing game well. It has been careful in not taking a strong ‘anti-China’ stand on the SCS dispute and its naval advances in the Indian Ocean using its waterways, even as it draws benefits from the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative.

Indonesia is playing the balancing game well. It has been careful in not taking a strong ‘anti-China’ stand on the SCS dispute and its naval advances in the Indian Ocean using its waterways, even as it draws benefits from the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Indonesia did participate in the Chinese flagship BRI Summit held in May 2017 and proposed projects worth $28 billion. Thus far, China, through the BRI, made investments in the Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Railway project, signed contracts for investing in two hydropower projects, one power plant and a steel smelter. These contracts were signed during the recent visit of Chinese Premier Le Keqiang to Jakarta. China’s investments and aid to Indonesia have increased significantly, particularly in infrastructure projects, ranging from bridges and roads to power plants and high-speed rail. Last year, China was the

third-largest foreign investor in Indonesia, with investments amounting to $3.4 billion ($4.5 billion). According to Indonesia’s Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) Chief, Thomas Lembong, China is investing heavily in Indonesia through the BRI. Both countries have agreed to jointly develop infrastructure projects in three Indonesian provinces specifically designated for BRI: North Sumatra, North Kalimantan and North Sulawesi. The BRI funding will cover three sectors — transportation, industry and tourism.

In the international fora, however, Indonesia has maintained that it is not very keen on depending completely on Chinese investments, as was evident from the statement of the Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs, during his recent visit to India: “

We don’t want to be controlled by the Belt and Road.” This is also perhaps one of the reasons for Indonesia to propose granting India access to develop the port of Sabang.

Indonesia’s ‘soft balancing’ against a rising China marks a remarkable shift from its traditionally non-aligned foreign policy. As the Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs had mentioned: “

We would like to be independent. We are too big to be leaning one way or the other.”

In its stand and actions on volatile issues Indonesia is being careful not to displease the Chinese sentiments. On the other hand, Indonesia by embracing the Indo-Pacific concept and granting India access to the strategic Sabang port is also trying to strengthen its relations with India. Thereby, Indonesia is trying to maintain a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region. It is pursuing an ambitious vision to become an active player in determining the future of the Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

Annexure

Indonesian Infrastructure projects considered strategic for BRI:

| No |

Project |

Sector |

Investment ($ M) |

Stage |

| 1. |

Trans-Sumatera Toll Road |

Transport |

27,700 |

Pre-Construction |

| 2. |

Sunda Strait Bridge |

Transport |

24,000 |

Planning |

| 3. |

Bontang Oil Refinery |

Energy |

14,500 |

Planning |

| 4. |

Jakarta-Bandung HSR |

Transport |

5,100

|

Awarded |

| 5. |

Central Kalimantan Coal Railway Network |

Transport |

2,300 |

Tendering |

| 6. |

West Coast Expressway |

Transport |

2,000 |

Project Signed |

| 7. |

Kertajati Airport |

Transport |

1,800 |

Tendering |

| 8. |

Soekarno-Hatta Airport Train Express Line |

Transport |

1,800 |

Design |

| 9. |

East-West MRT |

Transport |

1,700 |

Planning |

| 10. |

Balikpapan-Samarinda Toll Road |

Transport |

875 |

Planning |

| 11. |

Kulon Progo (New Yogyakarta) International Airport |

Transport |

700 |

Awarded |

| 12. |

Surabaya Monorail |

Transport |

558 |

Planning |

| 13. |

Kalibaru Port, First Container Terminal |

Transport |

393 |

Project Signed |

| 14. |

Manado-Bitung Toll Road |

Transport |

330 |

Planning |

| 15. |

Perbarakan-Tebing Tinggi toll Road |

Transport |

303 |

Financing Close |

| 16. |

Nusa Dua - Ngurah Rai - Benoa toll Road |

Transport |

253 |

Financing Close |

| 17. |

Southern Bali Water Supply |

Water and Waste |

219 |

Planning |

| 18. |

Surabaya Tram Line |

Transport |

210 |

Planning |

| 19. |

Umbulan Drinking Water Supply System |

Water and Waste |

151 |

Awarded |

| 20. |

Batam Waste-to-Energy Plant |

Energy |

133 |

Tendering |

| 21. |

Tangerang City Water Supply Project |

Water and Waste |

120 |

Project Signed |

| 22. |

Bandar Lampung Water Supply |

Water and Waste |

100 |

Tendering |

| 23. |

Bandung waste-to-energy Plant |

Energy |

68 |

Tendering |

| 24. |

Bandung solid waste management improvement |

Water and Waste |

65 |

Tendering |

| 25. |

West Semarang water supply |

Water and Waste |

56

|

Planning |

| 26. |

Bogor and Depok Solid waste management |

Water and Waste |

40 |

Planning |

| 27. |

Way Rilau Water supply system |

Water and Waste |

38 |

Tendering |

| 28. |

Palu water supply |

Water and Waste |

30 |

Planning |

| 29. |

Medan water project |

Water and Waste |

25 |

Awarded |

| 30. |

Tanah Ampo Cruise Terminal |

Transport |

25 |

Tendering |

| 31. |

Lamongan water supply |

Water and Waste |

17 |

Planning |

| 32. |

Maros water supply |

Water and Waste |

13 |

Planning |

| 33. |

Jakarta MRT, Line 2 |

Transport |

-

|

Planning |

| |

Total |

|

85,622 |

|

Source:

Pinsent Masons (2016)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This is the fifty eighth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles

This is the fifty eighth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV