US did not believe in the view that democracy could accomplish economic growth in Afghanistan. And their preference was authoritarian modernisation rather than through democratic means, according to Stanford University professor Dr. Robert Rakove.

The contemporary US perception of the constitutional experiment of Afghanistan was not very positive, according to Stanford University professor Dr. Robert Rakove.

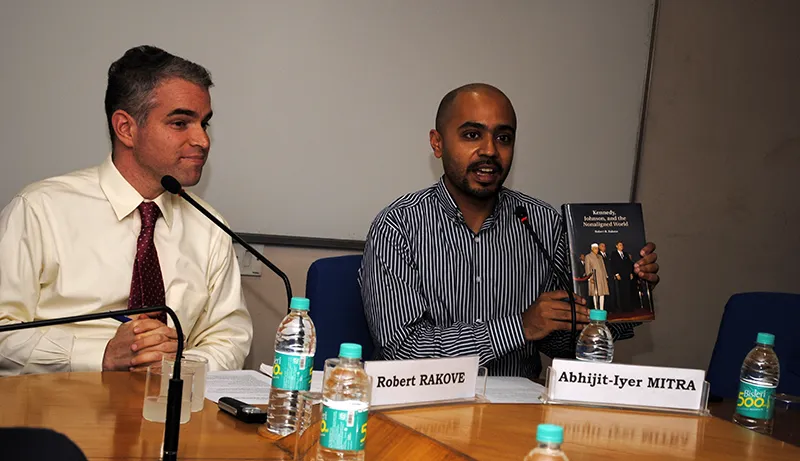

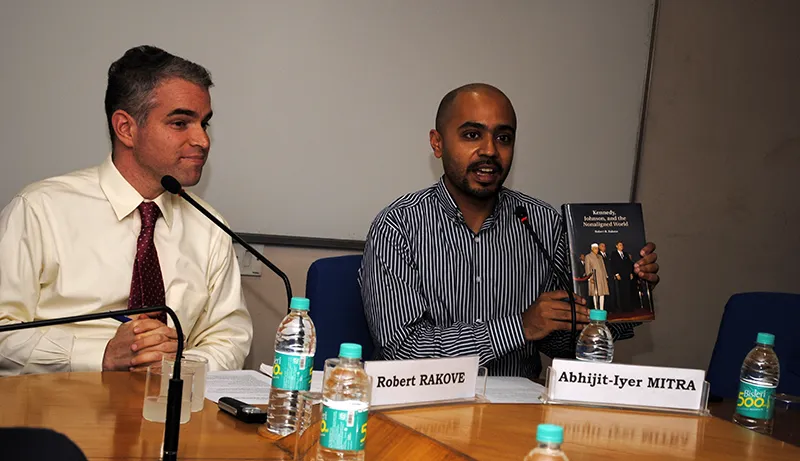

Giving a talk on "US-Afghan relations in the decades before the Soviet Invasion" at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi, on December 9, Dr. Rakove said US did not believe in the view that democracy could accomplish economic growth. Their preference was authoritarian modernisation rather than through democratic means, he said.

Dr. Rakove said that Afghanistan, in some sense, drove Americans to think seriously of the neutrality of the non- aligned world, emphasising how the United States accepted Afghanistan’s non-alignment and in fact tried to preserve it.

He said that US also made it clear to Afghanistan that they shouldn’t offend the Soviet Union on their behalf. This, according to Dr. Rakove, was quite a plausible policy. However, it had a number of loopholes which the speaker addressed one by one.

Dr. Rakove pointed out that the spreading détente between United States and Soviet Union did not work well for Afghanistan. Afghanistan’s ability to harness US support was compromised as a result of ebbing cold war tensions. There was a growth of cordial relations between US and the Soviet Union, he pointed out. Hence, from 1960s, US foreign Aid budget was declining. Dr. Rakove, said that Lyndon Johnson in particular saw foreign aid as a ship he could trade in for progress on other fronts. US aid dropped steadily, thus putting Afghanistan in a tough position.

He, however, highlighted that Afghanistan was not exceptional in this regard and India and Indonesia suffered because of the same.

Dr. Rakove further showed how the Afghan Prime Minister Mohammad Hashim Maiwandwal’s visit to US worsened the relations. Here Dr. Rakove mentioned an incident where Maiwandwal, getting agitated by a reporter, said that US needs to stop bombing in North Vietnam. President Johnson took this incident very negatively and commanded that all future Afghan aid requests must go by his desk even when he had much bigger tasks in his hand. This arrangement delayed the aids to Afghanistan which was struck by a serious food famine.

Dr Rakove explained that recent writings on US-Afghan relations only focused on the period of 1940s and 50s, thus ignoring the period of 1960s and 70s which was in fact a very crucial period for US-Afghan relations. He spoke about the lost decade of US-Afghan relations between1963-73. This was the time when Afghanistan was modernising and had opened its doors to the outside world.

He pointed out how at this moment of history no one would have called it a failed state. He said Afghanistan, despite becoming a theatre of cold war competition, managed to remain independent and non-aligned. And this period marked the peak of US-Afghan Relations. He pointed out how when Vice President Agnew visited Kabul, he wrote a letter to Ambassador Robert Neumann saying that Afghans were more like Americans than any Asians.

Referring to the present and previous set of writings of US-Afghan relations, Dr. Rakove showed how they linked the decline of US choice to decline aid to Afghanistan with Afghanistan’s shift of attention to Soviet Union for help. He said there were two variants of this thesis. First stated that, Afghanistan had always been an object of uninterrupted Soviet attention and what happened in late 1970s was a culmination of a long term design. The other variant of the thesis shows the heightening of Afghan-Soviet relations as consequential.

For Dr. Rakove, none of the two variants are satisfying. He argued how both the variants skip the period of constitutional experiment in Afghanistan which was in fact very crucial to understand the state of affairs. Secondly, he also argued how the second variant was true yet insufficient that is, for example, the Soviet training of Afghan Corps. According to him, it holds weight but does not suffice for an adequate explanation. He put forward the view that there was more at play and any one explanation wasn’t fully correct.

He concluded by stating that US’s stake in Afghanistan was profound and thus cannot be neglected. The question and answer session comprised of useful insights on the British influence on historical knowledge of the area on US policy formation. It was also pointed out that the influence of Soviet education system should also be taken into account while trying to understand the then Afghanistan.

(This report was prepared by Ananya Pandey, Research Intern, Observer Research Foundation, Delhi)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV