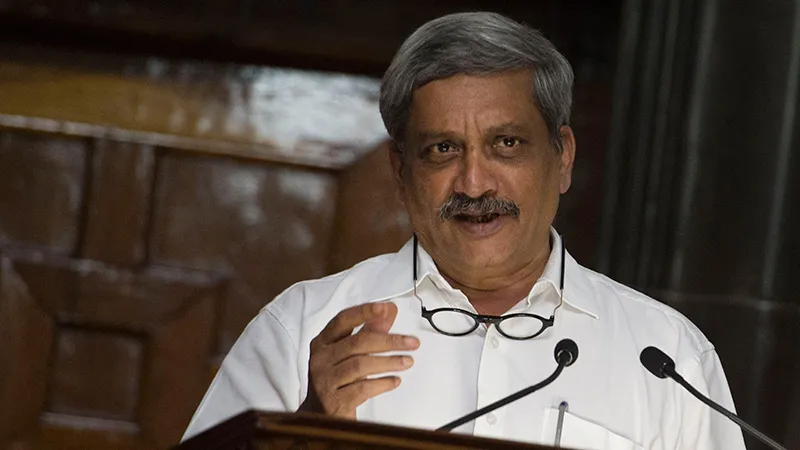

As India embarks on a renewed mission to compel Pakistan to course-correct by deploying all instruments of statecraft while simultaneously lobbying for a place in the global nuclear high table, Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar's musings will be noticed and filed up for propaganda value by those who seek to block both objectives. One imagines minions in Zhongnanhai and GHQ Rawalpindi to be exceedingly pleased with this enormous Indian self-goal.

Watching the defence minister's grandstanding — he was speaking at the launch of a very interesting new book that seeks to lay out a national security strategy for India in the 21st century — one is reminded of a late-night college bull session where a senior seeks to impress sophomores with his cleverness.

This is not the only bizarre statement from Parrikar. Not too long ago, the defence minister compared the Indian Army’s stance before the < class="aBn" tabindex="0" data-term="goog_962052896">< class="aQJ">29 September cross-LoC raids to that of Hanuman's before being blessed by the wisdom of Jamwant. Perhaps it would be more productive for the minister to explain why that uncalled for impromptu on nuclear weapons by a key member of Cabinet Committee on Security was a terrible idea.

First, and this is to state the obvious, the real utility of nuclear weapons are as tools of coercive diplomacy — to deter an adversary from initiating a certain action, or to compel it to change its position on a political issue. Nuclear weapons are primarily tools of bargaining, in other words. But in order for this to work, messaging around nuclear weapons (non) use has to be consistent across all stakeholders.

The first challenge that any new nuclear-weaponed state faces is to simultaneously assure its adversaries that its assets will not be used imprudently while seeking to reap political-strategic value from the mere possession of the same. Deterrence is primarily a psychological play buttressed both by resolve and restraint. Statements and restatements determine the moves and countermoves of a nuclear bargaining game whose overarching rubric is determined by a state and its adversary’s implicit or explicit nuclear-weapons policy.

Any off-the-cuff statement stands to vastly undermine the unwritten rules of this game with unpredictable consequences. This is why states are extremely reluctant to sharply change their nuclear postures, for the fear of upending the strategic calculus that upholds the "delicate balance of terror", to steal a phrase of Albert Wohlstetter, a leading Cold-War strategist. This is why — as an example — President Barack Obama's personal opinion notwithstanding, the United States has been extremely reluctant to adopt a no-first-use policy in a break with its historical position.

But while nuclear weapons are tools of bargaining, they are also determinants of national prestige. New members of the nuclear-weapons club often leverage their apparent responsibility as custodians of these weapons to seek concessions in international fora. This was the main reason why India — soon after becoming a declared nuclear-weapons state in 1998 — published a draft nuclear doctrine that had the imprimatur of the newly established National Security Advisory Board, after imposing a voluntary moratorium on further testing. The strategic benefits of this calculated stance of restraint were tremendous. It led to the landmark civil nuclear agreement with the United States and — more crucially — to a diplomatic de-hyphenation with Pakistan insofar as the US was concerned.

The BJP learnt the importance of not publicly toying with the declared doctrine the hard way, after its 2014 election manifesto — which promised a rethink on India's nuclear weapons policy — caused a furore both at home and abroad. Since coming to power it has backed away from its election promise.

None of this is to argue that India’s extant nuclear doctrine is perfect. Far from it, it is in urgent need of a rethink. For one, the doctrine of no-first-use that India ascribes to was predicated on the conventional military balance favouring India or, at worst, on parity with other powers in the region. Certain scholars have argued that Pakistan’s flirtation with nuclear maximalism — and its development of tactical/theatre nuclear weapons — presents significant challenges to the Indian doctrine, perhaps rendering it meaningless. China’s ongoing quest for asymmetric means of waging war, through anti-satellite and cyber weapons, could also force India to move from being a reticent nuclear power, with de-altered nuclear weapons systems, to a more forceful posture with an alerted nuclear triad.

But these discussions are — as they should be — carried out within the closed confines of the security establishment. And it is not the case that the informed public does not have any avenues to understand the contours of the debate that is likely to be taking place within the government, should it rethink India’s nuclear doctrine. They would just have to turn to the published writings of well-placed analysts with ideological affinities to the current government.

That the defence minister — and his loyalists — needs to be told all this is ironic. And troubling.

This commentary originally appeared in the Firstpost.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV