While India aspires to be a global leader and change agent, more than one-third of her children are still "abnormally skinny and abnormally short" as Angus Deaton put it recently. The president of the World Bank is on record saying that with 40% of its workforce having been stunted as children, India is simply not going to be able to compete in the future economy.

Recent research shows that the world has transitioned from an era when underweight prevalence was more than double that of obesity, to one in which more people are obese than underweight. However, countries like India are in a phase of the transition where the public policy challenges presented by overnutrition are in addition to those posed by undernutrition, instead of replacing traditional challenges of undernutrition.

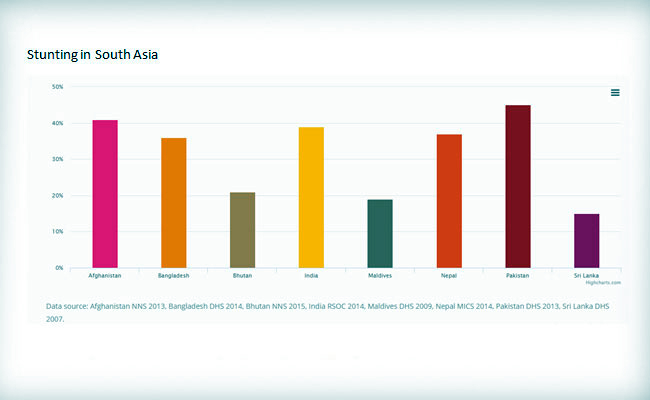

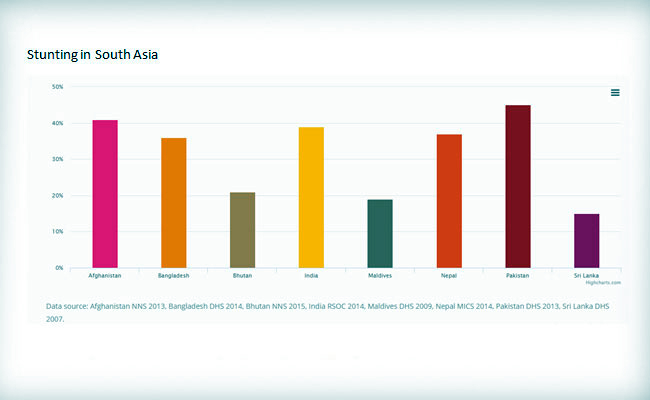

Undernutrition is the underlying cause of nearly half of deaths under the age of 5 in India, amounting to more than half a million deaths in 2015. India fares poorly compared to most other South Asian countries in terms nutrition outcomes, as the following graph on stunting (low height for age) shows. The Global Hunger Index (GHI) ranked India at 97 among 118 countries in 2016. According a Global Burden of Disease study published in the Lancet in 2016, out of the top ten risk factors in terms of disability-adjusted life-years in India, six were linked to nutrition.

Source: UNICEF South Asia Progress Report

Source: UNICEF South Asia Progress Report

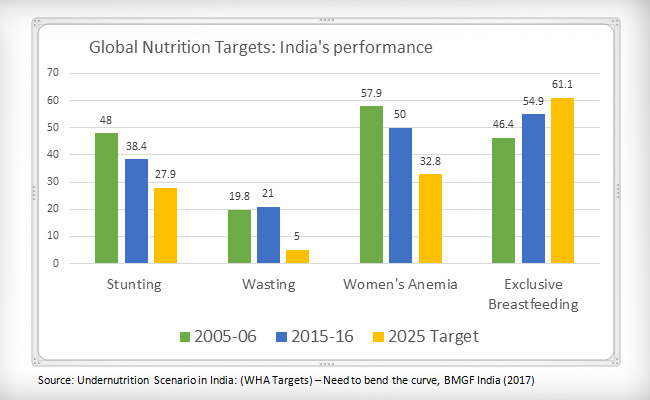

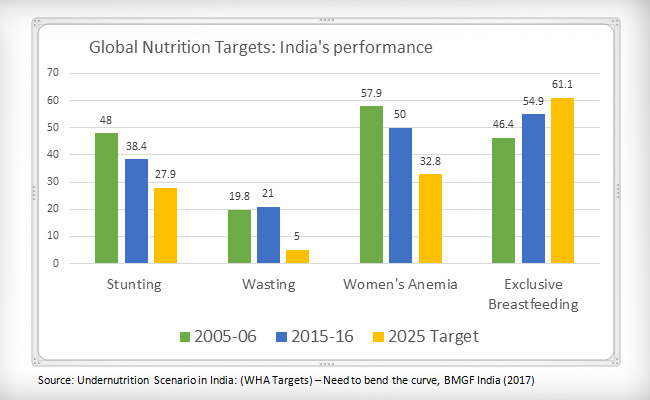

India has made considerable progress in child nutrition outcomes in the last decade. Data from the NFHS-4 show that levels of stunting, anemia, wasting, severe wasting and exclusive breastfeeding have improved in India between 2006 (NFHS-3) and 2016 (NFHS-4). Despite these improvements, 38.4% of Indian children remain stunted, and more than 21% wasted. Anemia among women has remained almost stagnant at 50% and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) levels remain low at 57%.

Barring Puducherry, Delhi, Kerala and Lakshadweep, all states have a higher proportion of stunted children in rural areas than urban areas. The slow rate of decline notwithstanding, it is a major concern that the percentage of children under 5 years who are wasted (low weight-for-height) actually increased over the last ten years, from 19.8% to 21%. The proportion of children who are severely wasted also showed an increasing trend, from 6.4% to 7.5% between 2005 and 2015, despite sustained economic growth over that time.

India has nearly halved the proportion of its stunted children (38.4%) from what it was in the late eighties (66.2%). However, the early gains are moving in reverse when it comes to wasting, and we are now almost at the same level of wasting as in the late-eighties (21%). Worryingly, states like Tamil Nadu, among the 'best performers' in reducing stunting, are among the 'worst performers' in terms of reducing wasting. States like Tamil Nadu and Goa represent states where relatively lower rates of stunting co-exist with high rates of wasting. In fact, Goa has a higher rate of wasting than of stunting.

Malnutrition affects India's growth

A recent study by the World Bank found that about two thirds of India's current workforce was stunted (too short for age) in childhood. This has enormous economic costs in terms of the reduction in per capita income. Stunting-induced per capita income reduction in India is found to be a staggering -13%, the highest in the world. Across South Asia and Sub Saharan Africa the average is around 10%.

Studies that have followed children from infancy through to adulthood find that inadequate nutrition in the early phase of a child's life has serious consequences in terms of cognitive development and health, leading to low energy, slower brain development and morbidity. This has a direct impact on education and adult productivity, in the form of lower wages. In addition, undernutrition in childhood has a strong link with chronic diseases such as diabetes, and may even increase susceptibility to obesity at later stages in life, as recent ADB research (2017) shows.

Stunting is just one aspect of the serious malnutrition problem India is grappling with. High levels of anaemia, wasting, a high proportion of children with low birthweight, emerging problems of overweight and obesity, and sub-optimal levels of exclusive breastfeeding contribute to the burden significantly. Recent studies have also shown that nearly one lakh children die every year in India due to diseases which can be prevented through breastfeeding. Inadequate breastfeeding alone is said to cost India's economy USD 14 billion every year through increased illness and health care costs and reduced productivity.

Stunting is just one aspect of the serious malnutrition problem India is grappling with. High levels of anaemia, wasting, a high proportion of children with low birthweight, emerging problems of overweight and obesity, and sub-optimal levels of exclusive breastfeeding contribute to the burden significantly.

India as well as other WHO members have promised to improve the nutrition situation across the board, as part of their Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) related commitments. However, the progress remains slow, and acceleration is needed for India to achieve Global Targets 2025, as the below graph shows.

Nutrition as an enabler of growth and development: A smart investment

Calling high levels of undernutrition a "stain on our collective conscience", Dr. Kim Yong Jim, the president of the World Bank recently called investments in "gray-matter infrastructure" — or investment in preventing malnutrition early in life — the most important investments we can make. He noted that this is especially because economies, are increasingly dependent on digital and higher-level competencies and skills.

India's Economic Survey 2016 acknowledged that while there are intrinsic reasons to invest in them, maternal and early-life nutrition programmes also offer very high returns on investment. Supporting early physical and cognitive development significantly affects the success of subsequent interventions — schooling and training — and outcomes in adulthood.

According to the latest Global Nutrition Report, the economic consequences of malnutrition represent losses of 11 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) every year in Asia, whereas preventing malnutrition delivers $16 in returns on investment for every $1 spent.

Averages hide the complete story

Looking at country averages doesn't tell the whole story. The absolute levels as well as rate of improvements have been highly variable across states and districts. Stunting in India shows huge inter-state variations as the following map shows. Whereas anaemia rates amongst women (15-49 years) have declined by 7 percentage points (from 67.4% to 60.3%) in Bihar, the prevalence of anaemia has increased by more than 10 percentage points in Himachal Pradesh.

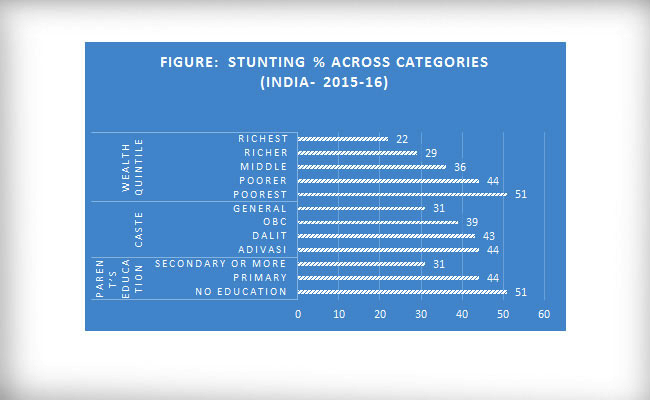

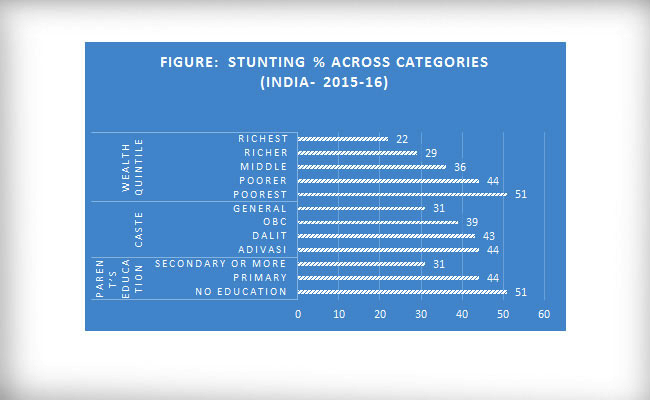

The strong socio-economic gradient of undernutrition is something that needs immediate policy attention. According to the latest NFHS (2015-16) data, the stunting rates for children under 5 across various socio-economic categories are given in the figure below.

Source: RCHIIPS

Source: RCHIIPS

Historically, nutritional outcomes have shown strong regional disparities and urban areas have consistently fared better when compared to rural areas of India. However, the last decade has shown a distinct departure from this general trend in some categories. Unlike stunting, which has improved across urban and rural areas over the last decade, wasting has worsened more in the urban areas, and stagnated in the rural areas.

The urban and rural rates of wasting are converging. In the last decade, while the proportion of wasted children has increased by half percentage point in rural areas, it increased in the urban areas by three percentage points.

There are stories of success in improving nutrition from states and districts. Analysis by the International Food Policy Research Institute shows that out of 640 districts covered by NFHS-4, only 29 districts have stunting levels between 10 and 20 per cent, and most of these are in the southern states of India. Interestingly, two of the top-ten districts in terms of lowest levels of stunting in the country are from Odisha, a state with an otherwise high stunting prevalence.

There are stories of success in improving nutrition from states and districts. Analysis by the International Food Policy Research Institute shows that out of 640 districts covered by NFHS-4, only 29 districts have stunting levels between 10 and 20 per cent, and most of these are in the southern states of India.

All states function under the same national policy and similar programmatic environment in India. Therefore, the variability in progress across states and districts is likely due to differences in determinants of nutrition and in the coverage of health and nutrition interventions. Understanding the causes of success and poor progress leading to variability within states is important to enhance policy and programmatic attention and to identify strategies to accelerate progress.

Way forward

The major nutrition policy challenges in India include addressing undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, as well as the emerging chronic disease burden linked to overnutrition. Policy documents acknowledge that undernutrition can lead to poor cognitive development in children and low productivity in adults.

Improving nutrition outcomes in India will require action to improve some of the major determinants of poor nutrition. For example, sanitation — NFHS-4 shows that while overall access to drinking water and electricity improved over the last decade, major determinants to malnutrition like sanitation continue to lag behind. The Swacch Bharat Abhiyan (SBA) shows an increased policy focus on sanitation, which is a critical driver of health and nutrition.

India has an opportunity in the form of the Sustainable Development Goals to radically correct course on nutrition and build a healthy and wealthy India. Greater integration between health and nutrition policy at each level of governance is the need of the hour, along with better governance and stronger political will to make nutrition a higher priority.

There is need for concerted action across both nutrition specific and nutrition sensitive interventions to accelerate progress on all the nutrition-related SDGs. This will help India secure the future of her children, reap the benefits of the demographic dividend and maintain strong and sustainable economic growth. The remaining parts of this series explore the state of stunting, wasting, anaemia in women, and exclusive breastfeeding, and discuss possible ways forward.

This commentary originally appeared in NDTV.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:

Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV