The politics around “demonetisation” — a misused term for what happened on 8 November 2016 — has taken centerstage in the run-up to the Assembly Elections in Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat (which goes to the polls in December). Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has added “morality” to the cluster of objectives, that seemingly justified compulsorily replacing 86 per cent of our currency with new notes over a short period of just two months last year.

Morality is a slippery slope to tread in public affairs. It’s certainly an individual virtue, but at a societal level it’s difficult to define. Consider the moral conundrums that arise while enforcing a law which doesn’t have widespread local acceptance. Rebels with a cause see themselves as morally-elevated outliers. Not so long ago, our freedom fighters were feted for disrupting the peace, assassination or damaging public property. Even today in areas like Kashmir or the Maoist belt in central India, it’s tough to apportion the balance of morality between those who violate the law and others who seek to enforce it.

Corruption is patently immoral as it saps national wealth. Measures to fight corruption are part of public dharma.

Our Constitution, quite properly, is silent about “morality”. A quasi-moral concept of “socialism” was introduced in 1976 into the preamble, by former PM Indira Gandhi, as a populist measure. But it sits incongruously with the otherwise liberal slant of the document.

Corruption is patently immoral as it saps national wealth. Measures to fight corruption are part of public dharma. The real issue is: was demonetisation essential to end corruption?

If the objective was to weed out counterfeit money, which can fund terrorism or even legal transactions, there was no need to impose a tight timeframe of two months. This is what caused widespread panic and disruption. It would have been enough to alert the public to the menace; provide markets (banks already have them) with testing devices to weed out “compromised” notes over time. This is an ongoing activity, that all central banks do routinely, because any note (besides crypto currencies) can be counterfeited.

If the objective was to capture the stocks of “black” money, held as cash, in one fell swoop, this was better done by making known “havens” of “black” cash — apparently entire warehouses — unsafe for storage through effective enforcement, coupled with strong incentives to come clean. Note that “black” money hasn’t gone away.

Demonetisation can do very little to stop generation of black money. The government knows this. It intends to use “big data” for surveillance of potential evaders; embed governance systems with enhanced oversight and enhance transparency. Only improved technology and perpetual, intensive oversight can starve this hydra.

Not least the timing of the move, just before the elections in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, which sends the largest number of members to the Rajya Sabha, where the BJP didn’t have a majority, could indicate the compulsion to play to the gallery. If this was the motive it worked very well politically — not least, because UP is a poor state with low governance indicators and high levels of inequality. Hitting the rich is a tested populist strategy, perfected by former PM Indira Gandhi, and still held dear by our antiquated Communist parties.

But demonetisation doesn’t align with Mahatma Gandhi’s precept that “means matter as much as ends.” Hitting tangentially at corruption, at the cost of scorching even the law-abiding, is unacceptable. Anti-corruption measures which ignore the social and economic collateral cost of implementation are suspect. The State has an asymmetric, fiduciary relationship of trust with citizens. Did it live up to its dharma of insulating the honest from State-induced actions intended to harm the corrupt?

Demonetisation doesn’t align with Mahatma Gandhi’s precept that “means matter as much as ends.”

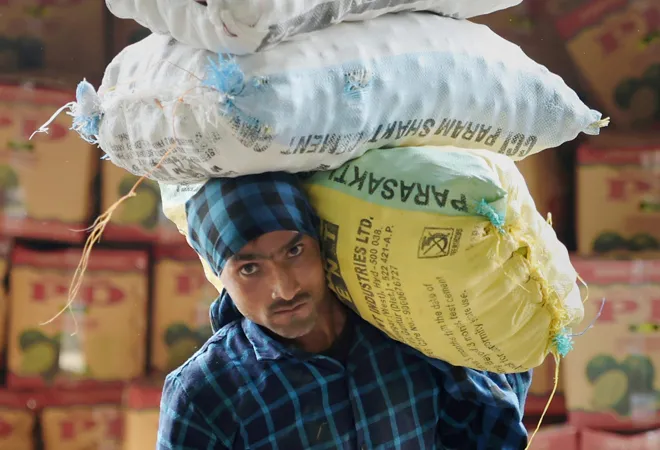

Undoubtedly, demonetisation did accelerate a shift towards banked transactions and boosted digital payments. Both outcomes are winners. But it’s also true that it put a temporary brake on economic growth by disrupting business and inducing job losses, mostly in the informal sector, where workers and the self-employed are less well paid, and less well-endowed to absorb the cost of a disruption.

Seemingly desirable steps to make the system honest can have grossly inequitable outcomes, which Gandhiji would have termed “immoral”. It’s possible to reduce corruption by replacing income-tax with a “head tax”. Citizens are more easily identifiable than their income, so very few would be able to escape this tax. If a “head tax” were to replace income-tax, each citizen would pay ₹3,600 per year. But consider, for 40 per cent of the population, which is vulnerable to poverty, the head tax would be a minimum 12 per cent of even the poverty level income of $1.90 per day. Currently, even an income of ₹10 lakhs, or 22 times the poverty level income, attracts a low effective tax rate. Protecting the weak is cumbersome. It creates tax escape routes, which need to be plugged with minimum collateral damage to the weak and the honest.

The good news is that the Narendra Modi government has got it bang-on with its second major corruption-busting initiative: the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Implemented from 1 July 2017, it has also disrupted business and compounded job losses, arising from the shutting down of businesses, which relied on the illegal competitive advantage of avoiding tax. GST is a potent standalone, medium-term winner. This expectation mitigates the interim economic “amorality” arising from the collateral harm to innocent workers and suppliers to such businesses. The proactivity of the GST Council in correcting mistakes and acknowledging errors has only deepened its credibility and conveyed a sense of responsible stewardship. This is welcome.

Demonetisation was misguided even if it had “moral” end-objectives. One-fifth of our population, which suffered the most, is in the income segment of ₹50,000 to ₹5 lakhs per year, being workers and those self-employed in the informal sector. They have still not been compensated. Hopefully, the finance minister will apply some balm in his 2018-19 budget and bring this tragic “morality play” to a happy end.

This commentary originally appeared in The Asian Age.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV