India's long-term growth strategy must be pegged to its labour force, whatever the economic model of choice maybe. This in effect means that attaining optimal growth rates would be difficult, to say the least, without the effective participation of women, who constitute half the country's population.

Recent surveys highlight consistently worsening gender parity in India's workforce. For instance, the 2016 Household Survey on India's Citizen Environment & Consumer Economy shows that only 27.4% of women in the working age group participate in the labour force — a figure that is markedly lower than several of India's neighbours, including China (63.9%) and Nepal (79.9%). Experts have correspondingly been pushing for gender sensitive policies — particularly women targeted job opportunities and skilling programmes.

The issue of gender sensitive employment, however, draws us to a fundamental question: Are women in India adequately equipped to exploit economic opportunities, even if such opportunities come their way? If not, then what are the factors holding them back? It is helpful to look beyond the obvious challenge of access to employment and skills. The availability of opportunities is of little value if women are unable to effectively participate in such gainful employment. Apart from training and jobs, investing in long-term human capital for women in India requires investments in their health.

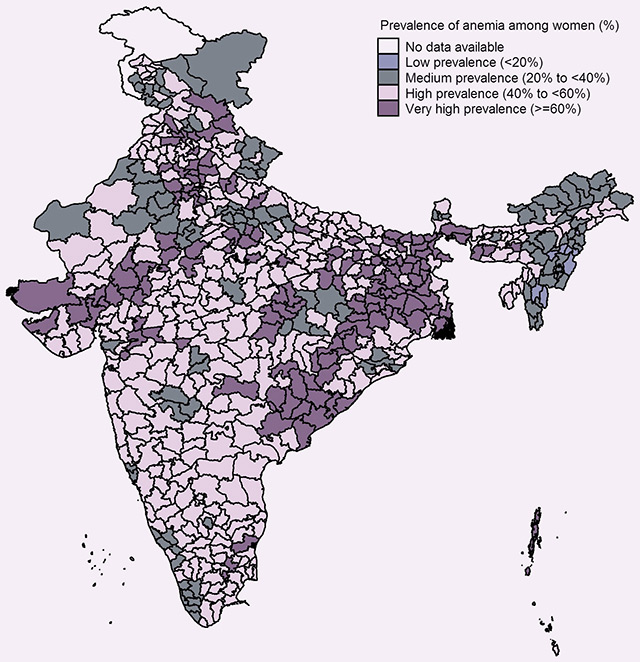

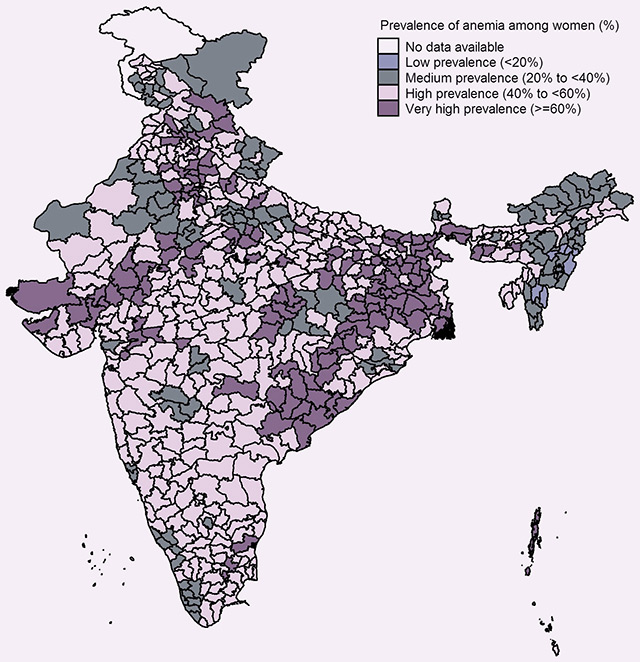

Given the social realities in the country, women are on the back foot from a very early phase — since childhood, they tend to be discriminated against vis-à-vis access to nutrition, health and sanitation facilities, or education. The issue of widespread anaemia is a case in point. The latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS) — India's most comprehensive dataset on health – shows that more than two-thirds of the total districts in the country suffer from a high (>40%) prevalence of the disease.

Prevalence of anaemia in India

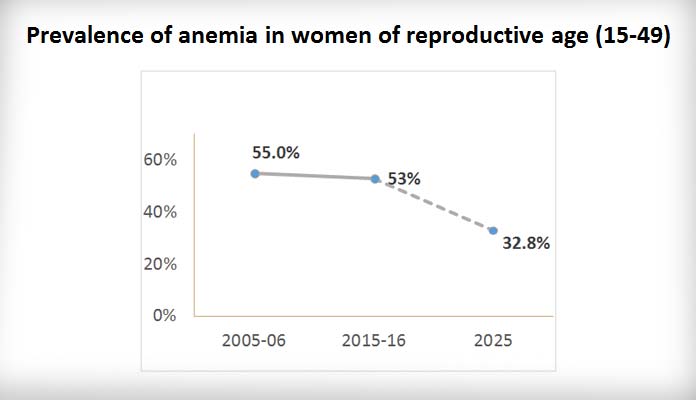

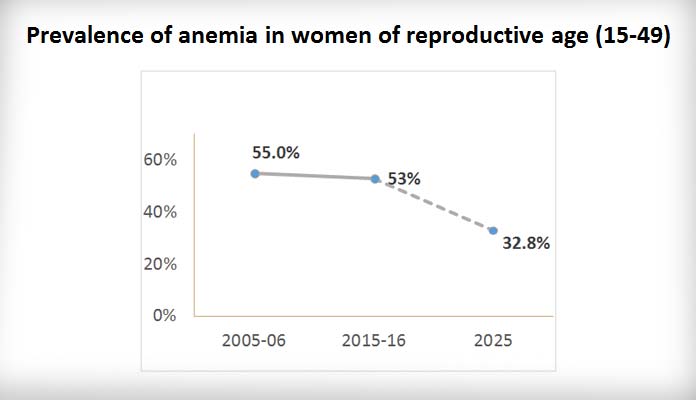

Tracking the prevalence of anaemia in India, a recently published report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) shows that anaemia among women in the reproductive age group has experienced only a modest decline from 55% to 53% between 2006 and 2016. Given that women belonging to this age cohort are also at their prime working age, this trend poses a dual challenge — economic and social.

However, analysis of disaggregated state level data illustrates that certain states have outperformed others. Here again, the NFHS-based IFPRI analysis offer valuable insights. For instance, the north-eastern states of Sikkim and Assam have witnessed a decline of more than 20 percentage points in anaemia among women of reproductive age. On the other end of the scale, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab have emerged as two of the worst performing states — experiencing a rise of more than 10 percentage points.

The prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women shows a similar trend. For example, Sikkim saw a sharp decline of 38.5 percentage points from 62.1% in 2006 to 23.6% in 2016. At the same time, 25 states and union territories fell in the World Health Organisation's severe category (>40%). Even among children, anaemia prevalence showed large state variations — highlighting the need to take a closer look at what some of the better performing regions have done right.

Tackling anaemia: What has the government been doing?

Given the severity of the problem, the government of India has been working towards targeted anaemia control through the National Nutritional Anaemia Prophylaxis Programme (NNAPP) for the last four and a half decades. Carried out through Primary Health Centres and sub-centres, NNAPP targets children within 1-5 years, and pregnant and nursing mothers, and provide them with iron and folate supplements.

Effective implementation has been a challenge, however, as evidenced by the sluggish fall in anaemia indicators. Health and nutrition specialists have pointed out that distribution of iron tablets under this programme has not led to corresponding consumption. This could partly be due to the lack of counselling provided. In an interview with Indiaspend, Dr Sutapa Neogi of the Public Health Foundation of India explained, "Iron tablets have many side-effects — diarrhoea and vomiting, for instance — which, during pregnancy, add to a woman’s discomfort." Yet, if these tablets are taken regularly, the reported side-effects are found to subside and the increased iron content in the blood leads to a significantly better quality of life.

The Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFS) programme, which has been in operation since 2013, has seen better results. Under this programme, adolescent boys and girls are provided iron tablets once every week for 13 months. In addition, the programme includes counselling to ensure that the children consume the iron tablets. Primary research on the programme provides key lessons pointing to the significance of this counselling.

Pondicherry emerges as a better performing region — both for anaemia in women and children. A 2015 paper on rural Pondicherry students showed that about 85% of those surveyed were reported to be taking regular doses. Teacher support reportedly played a key role in effective implementation — highlighting the need for continued motivation, proper information dissemination and supervision beyond mere distribution of tablets. Often, programmes stress solely on the provision of supplements, thereby neglecting the counselling component. The Pondicherry case highlights the importance of the latter.

Another key intervention is the need for an integrated multisector approach to tackling anaemia. For instance, severe anaemia is also associated with malaria and bacterial infection. Thus, access to sanitary facilities must be a part of a comprehensive anaemia control strategy. District level analysis of NFHS statistics provides further support to this argument. Districts with less than 20% households with access to improved sanitation facilities saw a 56% anaemia prevalence among pregnant women. On the other hand, those with more than 80% households with improved facilities experienced a low 36% prevalence. Education is another factor — the fear of side-effects and misinformation emerge as primary barriers to regular intake of the provided iron supplements. Further, districts with higher open defecation and more women married under the age of 18 tend to experience higher proportion of pregnant women affected by anaemia. As we move ahead, programmes must be designed taking these interlinkages into account.

We must also understand why anaemia persists in India. To do so, we need to trace the entire life of a woman. The vicious cycle of anaemia begins right from the first year of birth. Children, especially female children, often grow up lacking access and thereby consumption of iron-rich food sources. The consequences of this lack of access worsens as girls progress to adolecensce: this is because, in addition to the increased iron requirement for growth and development, adolescent girls need further iron-rich nutrition due to the onset of menstruation and the loss of blood every month. This often triggers adolescent anaemia, which is further aggravated during pregnancy.

Anaemic women tend to be at a higher risk of maternal mortality, and are more likely to go through miscarriages or deliver stillborn babies. A 2014 nutrition study found anaemia to be the primary cause of maternal mortality, leading to half of the total maternal deaths in the country.

And this cycle of poor nutrition continues into the next life cycle. Even when the baby of an anaemic mother is safely delivered, research shows children born to anaemic mothers are prone to other development disorders and tend to have low birth weight. Anaemia could lead to five to ten per cent lower intelligence quotient (IQ) among children. Thus, tackling anaemia calls for targeted interventions at specific stages — childhood, when it begins; adolescence, when it worsens; and during pregnancy, when it is further aggravated.

Even among developing nations, India continues to lag behind most in dealing with anaemia. According to the Global Nutrition Report 2016, India ranks 170th among the 180 nations surveyed for anaemia among women. Widespread anaemia has serious consequences for economic productivity, especially among those engaged in physical labour. Anaemia leads to lethargy and fatigue, which have a direct adverse impact on work performance. According to a nutrition report published in 2003, 0.9 per cent of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) is lost due to iron-deficiency anaemia. This amounts to USD 20.38 billion based on the World Bank's 2016 Indian GDP figures.

Realising India's health sustainable development goal and growth demands concerted efforts to tackle anaemia. In 2012, India also committed to achieving the six World Health Assembly targets on nutrition — one of these is a 50% reduction in anaemia prevalence among women of reproductive age. Lessons learnt from past programmes must be leveraged.

At the grassroot levels, teachers, school counsellors and frontline health workers must be specifically trained on this issue, given the central role that counselling plays. At the macro-level, anaemia control programmes must shift to a state-centric and state-led approach given the large inter-state variations. A major part of how the Indian growth story plays out will hinge on the country's success in delivering the right to life, health and livelihood for all Indians, including India's girls and women.

This commentary originally appeared in NDTV.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV