A ₹2,000 crore hike in budgetary allocation to the water resource ministry towards revival of Ganga is a welcome move by this year’s Union Budget. However, history serves up a warning. Despite the completion of two Ganga action plans and generous fund flows – ₹900 crore spent over the last 15 years — the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2017 had observed that, “not a single drop of the Ganga has been cleaned so far.”

With a budget outlay of ₹20,000 crore to be executed over five years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s pet project — Namami Gange — launched in 2014, must therefore learn from the past mistakes.

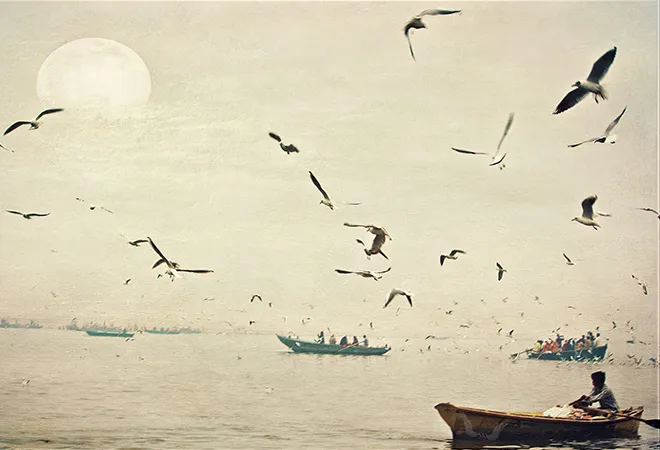

For north India, Ganga is at the heart of its cultural and economic landscape. The 2,525 km long Ganga flows through Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and Bengal before reaching the Bay of Bengal. Along with its tributaries, it covers 11 states that are home to 600 million people and serves water to 40% of India’s population. The river is currently struggling to cope with the sewage waste and industrial effluents dumped into it. Given its religious and industrial importance, any further deterioration would have significant ramifications.

In his Budget speech, finance minister Arun Jaitley has claimed that cleaning of Ganga “has gathered speed, and 47 out of 187 sanctioned projects have been completed.” Whereas, the latest National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) report updated on December 2017 reveals that only 18 projects have been completed in the last four years, of which none are focussed on the key areas of rural sanitation, industrial effluent monitoring, afforestation or biodiversity conservation.

Namami Gange lays much emphasis on pollution abatement through improvement of sewage infrastructure. A majority of sanctioned and completed projects therefore are sewage treatment plants (STPs). Yet, until December 2017, Namami Gange had created only 228.13 million litres per day of the 2,278.08 mld sewage treatment capacity it aimed for. With a large section of the country’s urban population living outside the sewage network, a huge amount of waste generated does not get conveyed to the STPs.

In the absence of a well-connected underground sewage system, STPs would continue to suffer from shortage, under-evaluation and underutilisation. More advance groundwork at the primary stage of assessing the scope of the problem is imperative to develop adequate supportive infrastructures for successful execution of STPs.

However, piecemeal efforts on big STP projects would not lead to any significant impact. A plan to clean Ganga needs to shift focus from such centralised large capital expenditure projects, to a decentralised process that undertakes cleaning-up from upstream to downwards, progressing through each watershed before entering the major trunk channel. Creating a comprehensive and robust real-time map of pollutants and their respective sources would help in effective monitoring of the problem. As 12 major tributaries source the Ganga, its rejuvenation would not be possible without clear rejuvenation strategies for each of its tributaries.

Ganga’s freshwater ecosystem has also been severely affected by industrial discharge. A CAG report has revealed that during 2016-17, the level of pollutants in the river across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Bengal was six to 334 times higher than the prescribed levels. Strict monitoring and action is required from NGT against the polluting industries found non-compliant with prescribed effluent discharge standards. Introducing new statutes on making the polluter pay or treating the polluted water before it enters the system would prove to be an effective solution.

The most delicate problem is the pollution associated with cultural and religious festivities. The Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board estimated that the Maha Kumbh Mela in 2013 — where 120 million people participated — saw 70% increase in the organic pollution level in the river. As the Ardh Kumbh is scheduled for next year, both the central and state government should put in place well thought out strategies to deal with the problem.

It is time to move beyond mere allocation of money and do serious implementation on the ground. Else, as the Supreme Court has once remarked the government, “it seems Ganga will not be cleaned even after 200 years.”

This commentary originally appeared in The Times of India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV