Christy Lee: Why does your status say "single" on your Facebook page?

Eduardo Saverin: What?

CL: Why does your relationship status say "single" on your Facebook page?!

ES: I was single when I set up the page.

CL: And you somehow never bothered to change it?

ES: I..

CL: *looks at him sternly* What?

ES: I don't know how.

CL: Do I look stupid to you?

ES: No. Calm down.

CL: You're asking me to believe that the CFO of Facebook doesn't know how to change his relationship status on Facebook?

ES: It's a little embarrassing, so you should take it as a sign of trust that I would tell you that.

CL: Go to hell.

ES: Take it easy.

CL: No! You didn't change it so you could screw those Silicon Valley sluts every time you got to see Mark.

In case you missed the movie, those are lines from The Social Network, the acclaimed 2010 film about how a brilliant and prickly Harvard sophomore began Facebook, now the world’s largest social network.

Conversations like the one above, born on social, set a match to millions of relationships, new bonds cleave on the same media, old school buddies reclaim the past, those of us who forget to carry pen and paper to note down phone numbers can most likely ping that someone we met yesterday.

If you have a Facebook account, you probably remember how you joined.

< style="color: #0180b3;">Why do you post? Why do you share? Does where you live matter to how you post?

12 years after Mark Zuckerberg took the idea of local relevance and sharing global, the most extensive study of social media has just reported back. The Economist ran a starter piece on the study — The medium is the messengers, which argues that “sooner or later, the doubters (of social media) either convert, or die.”

For Why We Post, the largest anthropological study ever commissioned, nine scholars fanned out across 15 months to various field sites, and the results have begun to unravel as we text necks continue to watch wide eyed, for more on this inexact science often panned for its many risks. 11 books are expected in the next 12 months and “each book is as individual and distinct as if it were on an entirely different topic.”

Led by Daniel Miller of University College, London, this study is defined within anthropology because it analyses, without a rulebook, what people actually do and why, and attempts to layer our understanding of variations from these norms.

Among the 15 countries covered are Brazil, Chile, China, England, India, Italy, Trinidad and Turkey.

Early on in Why We Post, Miller and his colleagues confront the predictable push –back based on the choice of field sites, the scope of study and the number of respondents.

For example, if South Indian men in an IT–heavy field site are wooing foreign women online, that may not hold true for what’s happening, in say, New Delhi or Hyderabad, or even what others may be posting. India has the world’s largest population and multiple cultural identities. What is true of social media usage in one agro–economy turned modern may not hold well in another city or micro culture even within the same country.

The survey results are based on a total of 1199 responses across all nine field sites.

The results of Why We Post — “are never intended to make claims that homogenise populations” — the researchers admit early on. Hyper–local is where this is headed.

< style="color: #0180b3;">It’s not social media that has changed the world, but quite the opposite — “the world has changed social media.”

Depending on your country and culture, local factors determine how you post and there are local consequences.

To share your identity, to vent your anger at political apathy, you do not need to own a printing press or the airwaves, or know someone who does. To that extent, yes, social media has made people feel more empowered.

Rather than paint social media as something that takes away from life, the study approaches the subject with the “attainment” view — just as you learn to drive a car, so you learn to live with and profit from social. How social media is used is central here rather than why it’s wrong or right.

< style="color: #0180b3;">The Why We Post results coincide with another exhaustive study — misinformation on social media as a “global risk”.

The approaches vary — Why We Post finds its roots in empathy — trying to understand how each man or woman uses social media, while the “global risk” study is deeply mathematical drawing from what has already gone awfully wrong.

“We view social media as integral to everyday life in the same way that we now understand the place of the telephone conversation as part of offline life and not as a separate sphere,” reads the first of many hundred pages.

If Why We Post seeks to understand why we learn to drive a car, the “global risk” study charts the data on car crashes on a high speed freeway.

North America has been excluded from the study because of its over–representation in social media research, but this article includes data narratives on American patterns.

Why We Post — 10 key research topics

• Education and young people

• Work and commerce

• Online and offline relationships

• Gender

• Inequality

• Politics

• Visual images

• Individualism

• Do social media make people happier?

• The future

Dateline Social

• Facebook, found on 2004

• Twitter, found on 2006

• WhatsApp, found on 2009

• Instagram, found on 2010

• Snapchat, found on 2011

• WeChat, found on 2011

Selfies and memes — sharing memory, circulating dissent

The horror of selfie critics is often justified by the number of people who fall off cliffs and beachfront hotspots trying to get the perfect picture.

Many of the perspectives of the UCL study refute the naysayers, claiming that selfies may represent a more socialised and less individually focused activity than traditional photography.

“This circulation of images reinforces sharing current experiences, as well as sharing memory.”

In Brazil, many selfies posted by men were taken at the gym, Chileans have come up with another genre — the ‘footie', Britons have developed “uglies” precisely to counter to narcissism critics. British school children post five times as many ‘groupies’ as they do ‘selfies’.

“Social media photography seems to be associated with the decline of make–up and the ubiquity of clothes such as jeans and t–shirts as a landscape of unpretentious modesty,” says the study.

In Italy, women post far less selfies after marriage, this same pattern reflects in decreased posting about family and babies too!

In India, memes focus on religion and politics; Trinidadian memes are mostly about politicians, helping discourse with strong ideological messages, but without getting on the wrong side in an obvious way, or commenting on a burning issue in isolation.

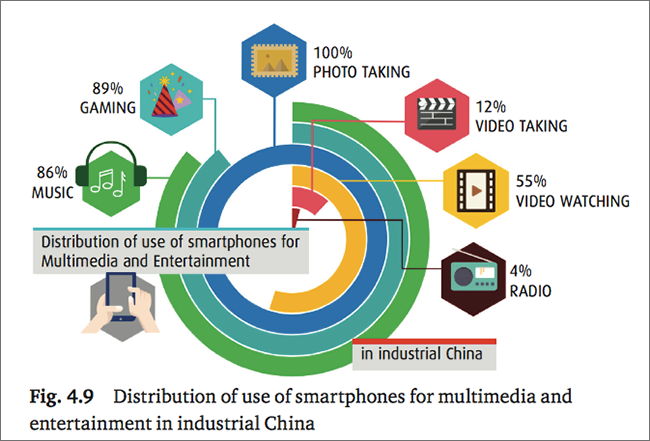

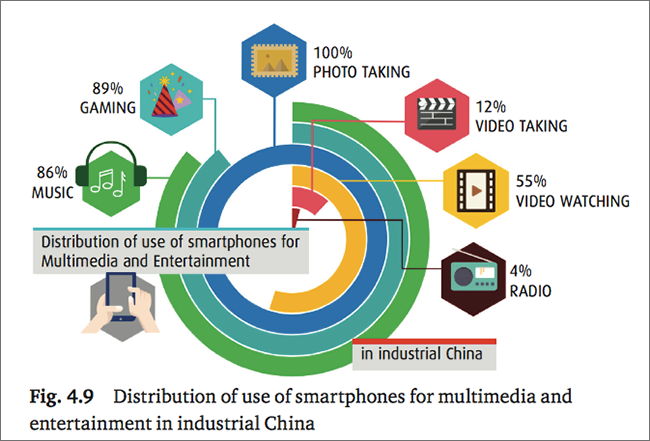

For China’s labourers, social is a “lived” space

The world has rarely been as mobile as it is today. This means different things depending on how much money you have.

Migrant labourers toiling in China’s factory work, sleep and eat offline, but turn to their online personas to “live”. With no time to build relationships offline, social media for them is a “living space” that is not fantasy or merely entertainment.

The commonly heard disdain for social media could well be a conspiracy, although not entirely conscious and premeditated.

“We can also see how in some cases the denigration of social media as inauthentic may in part be the practice of elites. Such groups, secure in their power to construct themselves offline, may seek to dismiss the attempts by less powerful populations to assert the authenticity of their self–crafting online.”

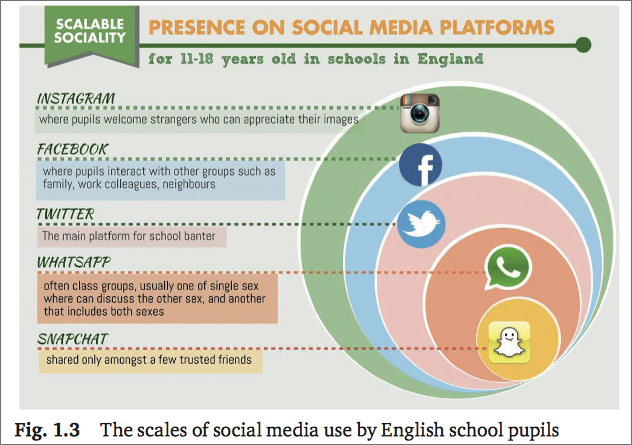

How English school kids use Instagram

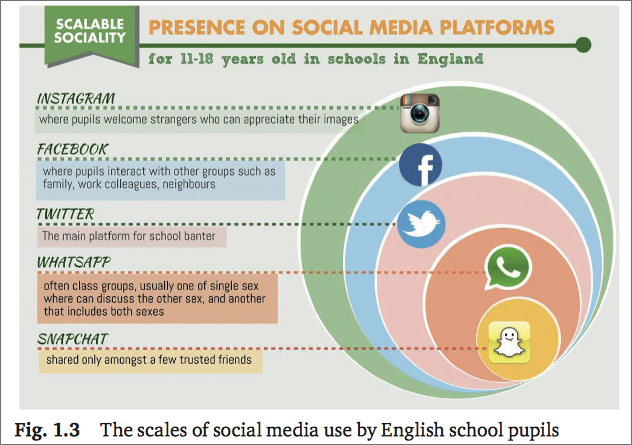

A survey of nearly 2500 school students in England found a fine example of poly media use — different social media sites — to meet different social needs or “social scalability” as the study calls it.

To speak with a bestie, the surveyed students used the plain old straight on text message.

On WhatsApp, it’s usually groups of boys who can talk about girls and vice versa.

Twitter forms the main site for school small talk and often includes students from other classes in that year. Facebook and Instagram are the outermost orbits where it’s more than just schoolmates. While Facebook linked the students with family and neighbours, Instagram is the only site where they welcome strangers, says the study — “because the contact shows that someone who the children do not know has appreciated the aesthetic qualities of the image they have posted.”

Note the way that Twitter is used — for banter — that differs from the way adults use it for information and quick fix news from multiple sources with the same hashtag.

< style="color: #0180b3;">School jokes have not always been on Twitter, they have migrated there from Facebook.

“Is the ‘true’ Twitter the one used for information, or the one used for banter?” asks Daniel Miller, professor of anthropology at UCL.

Just as the distinction between the virtual and real has blurred and social media is no longer the exclusive preserve of media or communications folks, media platforms’ purpose is defined by its users and their location, and both will keep moving.

What we do with social media is “latent in our humanity” says the study.

‘Hyper–conservative’ on Facebook

Despite the initial enthusiasm about technology erasing strict gender identities, the UCL study shows that technology is “neither patriarchal nor liberating.”

“Public online spaces have emerged as often highly conservative, reinforcing established gender roles. Self–crafting on social media continues to have a gendered aspect, as one part of an individual’s various intersecting identities, just as in everyday offline life.”

< style="color: #0180b3;">In southeast Turkey, women rarely post about their interaction with men on Facebook pages that their friends and relatives can see.

They even stay away from posting about mixed gender meetings in public places like cafes because of the “gossip and misunderstanding” potential.

In fact, conformity to social norms that please elders is much tighter on Facebook than offline because of the “continuous scrutiny” from relatives and friends who may call to check and clarify.

Trinidad offers a contrast where Facebook is called the ‘Book of Truth’. A person’s social media profile is the “curated truth” of his or her identity — reinforcing what is already visible — making it “hyper–visible”.

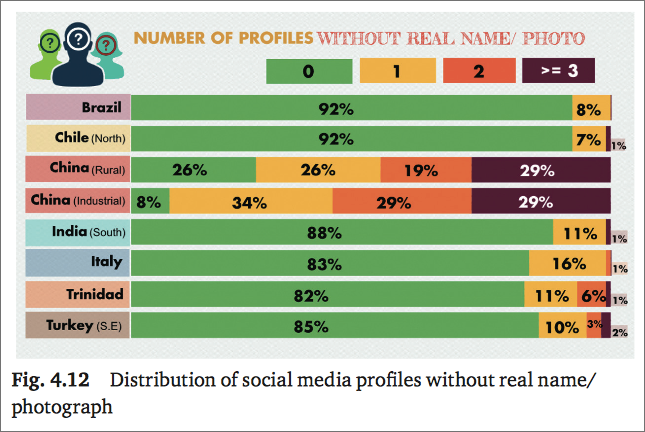

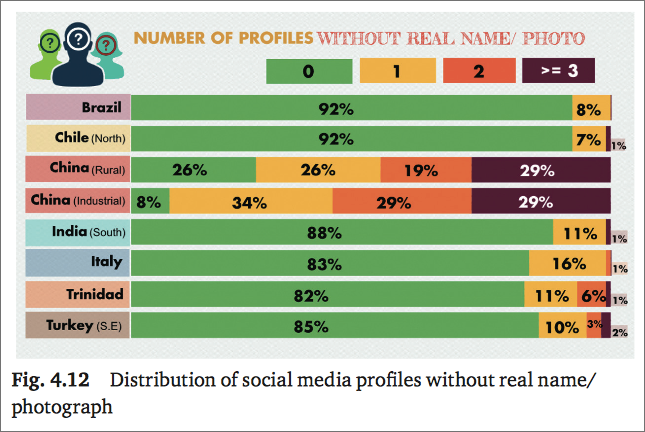

Women break out of conformity with fake accounts

In the same Turkey where women hyper–conform on social, they also break the mould with some help from fake accounts.

House bound women here commonly use fake accounts to keep in touch with people their husbands and fathers may not approve of, or pursue study they are not allowed to.

In industrial China, social media is where workers rebel against offline oppression.

“Men appear to display a greater variation between their online and offline lives than women do. In their daily life, they must respect clear masculine norms that do not include romanticism, sweetness and sensitivity.”

By contrast, on social media they share the same posts about romantic love that are shared by women, and “post” their resistance to society’s expectations which they would not dare try offline.

In Italy, women rarely stop and talk in the streets for fear they would look lazy. Social media fills their information and gossip gaps.

South Indian men are wooing foreign women

S. Venkatraman who led the South India research says young men in his field site “generally lied” about their social status, where they study or work, in the belief that such claims up their appeal. Venkatraman spent 15 months in Panchagrami (pseudonym), a particularly complex area, which has morphed from an agro–economy into one which caters to 200,000 IT workers who travel here to work. Originally a group of five villages, Panchagrami is now the site of a government sponsored IT park.

“In the Indian field site, in common with those in southeast Turkey and rural China, this desire to experience new intimate and friendship relations propels both women and men into a far wider network of people.”

The rise of WhatsApp

Just to sample how fast social media adoption has been, when the UCL field studies began, Trinidadians were chatting on WhatsApp at a time when it was barely known in England. Fifteen months later, when the fieldwork had finished, WhatsApp had become such a global rash — “we could hardly imagine they did not previously exist.” In India, Reliance Jio’s Jio Chat has the capability of having 500 people in a single group. WhatsApp recently upgraded to groups of 256.

Social media may dump its odd name

Since communication has always fulfilled a social need, it’s going to get harder to keep saying social media and expect that it is understood as a certain bunch of platforms. Its success will lie in its death as a separate sphere, predicts the study.

Facebook seems to have lost its cool among young people in England. There is growing evidence of the same in America’s high school kids.

For many marginalised populations, especially women, social media, as we know it, does seem to have emancipatory effects for many, says the study.

Is social media making humans less so? No, they’re “merely attaining something that was latent in human beings," says Dr. Miller.

Are online relationships replacing offline ones?

No, they are reinforcing what already exists — which is the “mediated nature of prior communication and sociality, including face to face communication.”

The story goes that Zuckerberg once told colleagues that “a squirrel dying in your front yard may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.”

That “relevance” of what’s happening has also not changed one bit, social media merely represent a change in where all could be seen and heard at the same time.

“The way Chinese people socialise around food, English people around pubs, Trinidadians around partying, Indians around extended family or Italians around public space are almost always reproduced on social media.”

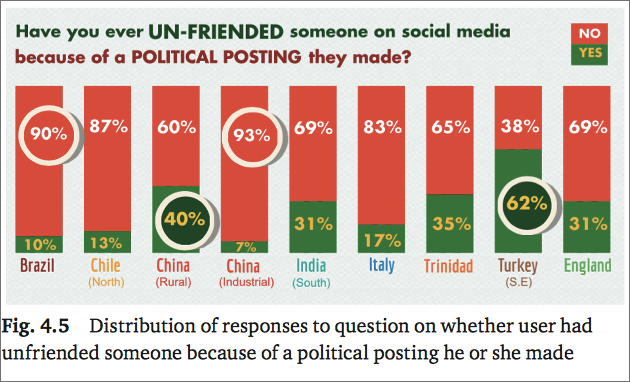

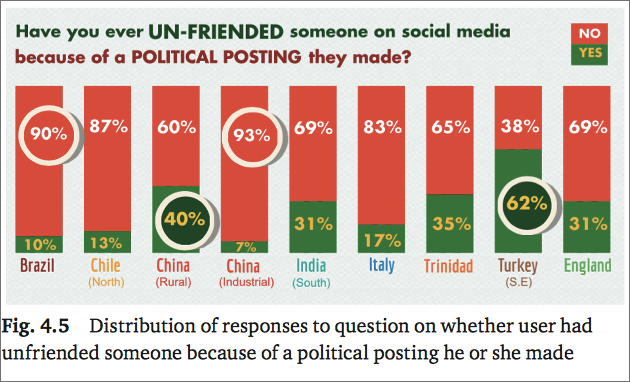

Megaphone for rebellion: #KanhaiyaKumar, #JatQuotaStir

In her new book, The End of Karma: Hope and Fury Among India’s Young, Somini Sengupta speaks of the siege in India’s capital city New Delhi when public outrage spilled out on the streets and on social media simultaneously — #KanhaiyaKumar and #JatQuotaStir.

Indians’ median age is 27 and every month between 2011 and 2030, nearly one million Indians will turn 18.

The thread running through Sengupta’s book mirrors the UCL research —that if culture is an enemy — the way younger populations use social media only helps to express the same anger — and let it be seen without needing control of either the airwaves or print media.

The Arab spring in 2011 when Hosni Mobarak’s government was toppled started with an anonymous Facebook page.

While the internet has facilitated political mobilisation, harnessing piles of data is what is delivering results and influencing political outcomes. More and more data are only having power in the hands of those who are already powerful.

< style="color: #0180b3;">Social media gives new tools to the powerful.

The way phones and telecom services are being fashioned to become part of users’ persona, the social media they hold within their screens tend more to mirror popular cultural values than become distinct. Future nicks and tucks will likely showcase more affinity to local culture.

The Economist predicts that 80 per cent of the world’s adult population will have well connected smart phones by 2020. The largest young population on the planet — in India — is smartphone hooked. Already the 10 biggest messaging apps represent three billion users. Our work follows us home, families follow us to work, all on our phone screens. We can have almost entirely visual conversations on social, but none of this means that each person with a smart phone or countries with large populations and high social media use are going to suddenly be represented more often on Google search results.

Just the fact of owning a smart phone and having social media accounts does represent a form of greater equality. To that limited extent, social media is democratic, but does not translate into offline equality.

Only Facebook, Google, governments, costly political campaigns like the $5 billion US election and cash rich businesses have enough money and data to make sense of the network dynamics and learn how to profit with targeted messaging.

Although social media platforms add to the total sum of democracy, just the way you can buy a bike or a car and ride it on the street, it does not give you the influence to barricade that street when those in power drive by.

What it does instead is to give the powerful new tools to tighten their grip.

To get 5000 retweets (like Donald Trump) or 10,000 retweets (Indian cricketer Virat Kohli on his friend Anushka Sharma) you don’t need democracy, you need power. That has not changed.

The author is Senior Editor at Firstpost, and is based in New York. Follow her on Twitter: @byniknat

Bar graphs used here are courtesy the study: How the world changed social media | Image courtesy: Reuters

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV